|

|

|

On Kunio Mayekawa

Thomas Daniell |

|

|

|

Catalog:

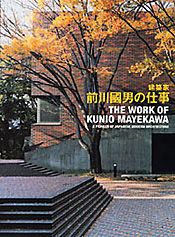

The Work of Kunio Mayekawa:

A Pioneer of

Japanese Modern Architecture |

|

The year 2005 marked the centenary of the birth of architect Kunio Mayekawa (1905-86),

a pivotal figure in the inception and development of modern architecture in Japan.

As an apprentice to Le Corbusier (inarguably the greatest modernist architect

in European history) and a mentor to Kenzo Tange (arguably the greatest modernist

architect in Japanese history), Mayekawa forms a crucial link in the import of

Western architectural concepts and techniques into Japanese architectural design,

construction practices, and even urbanism. A superb retrospective exhibition was

recently held at Tokyo Station Gallery, assembled by a group of Japan's leading

architectural historians. Comprising photographs, drawings, models, videos, original

sketches and blueprints, its contents have been collected in a comprehensive bilingual

catalog, with a wide range of scholarly essays and excerpts from Mayekawa's own

writings.

As has often been noted, the introduction of modernist architecture to Japan was

a relatively painless process; whereas the austerity and simplicity of modernism

was intended as a challenge to the florid decoration of European architectural

history, in Japan it had a direct resonance with traditional aesthetics. Japan

also had the demographic exigencies and urban densities that seemed to warrant

the regimented masterplans of modernism -- and, perhaps, a social and cultural

consistency that would allow them to be successfully implemented. Yet although

Mayekawa had acquired from Le Corbusier the essential principles of modern architecture,

more importantly, he understood modernism as a mode of constant invention rather

than as a set of formal rules, and was thereby able to convincingly adapt it to

the Japanese cultural and climatic context.

This can perhaps be attributed to the fact that Mayekawa worked in Le Corbusier's

Paris atelier from 1928-9, a critical moment in the evolution of Corbu's own work.

It was the end of a fruitful decade, comprising his so-called "white period"

and the development of the compositional paradigms that culminated in the seminal

Villa Savoye. Yet even as Villa Savoye was under construction, the relentlessly

experimental Corbu was already developing projects that were a reflexive critique

of the problems that had emerged in his built work to date. Despite being involved

for a mere two years, Mayekawa was thus simultaneously exposed to the apotheosis

of the modernist "machine for living" and to a critical reevaluation

by its originator.

After returning to Japan in 1930, he spent five years at the office of Antonin

Raymond (a former assistant to Frank Lloyd Wright), and then established Mayekawa

Associates in Tokyo's Ginza district. With the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war

in 1937, Mayekawa opened branch offices in occupied China, and designed a number

of significant projects for those regions of Asia annexed by Japan. It was during

this period that the young Kenzo Tange was a staff member in Mayekawa's office.

Throughout his career, Mayekawa presented himself as a rebel and social critic.

He acknowledged Le Corbusier's manifesto L'Art Decoratif d'Aujourd'hui (1925)

as the original impetus for his move to Paris, and later translated and published

a Japanese edition, as well as writing polemical texts that drew heavily on Corbu's

style. Yet Mayekawa was far more than a disciple and interpreter. As the exhibition

makes clear, he was an innovator at every level, from construction materials to

social programs.

Mayekawa's early attempts to use exposed reinforced concrete in Japan were frustrated

by the poor quality of construction. Air pollution would cause the surfaces to

quickly stain and crumble, so he developed customized ceramic tiling systems with

a perceptible thickness and tactility that transcended mere veneers. While in

Paris, Mayekawa had been heavily involved in the development of Le Corbusier's

Maison Minimum, an inexpensive industrialized duplex residence responding to the

massive housing shortages in Europe after the First World War. Two decades later,

in the aftermath of the Second World War, Japan was confronted with identical

problems, for which Mayekawa developed a prefabricated wooden house system named

PREMOS (the M in the acronym stood for Mayekawa himself).

Perhaps Mayekawa's legacy is best embodied by the pioneering Harumi Apartments

(1958), a modernist concrete skeleton containing traditional Japanese interiors,

built on a platform of reclaimed land in Tokyo Bay. Taking an unambiguous position

in the debate on maintaining tradition versus encouraging modernization, it also

adumbrated many of the concerns of the Metabolist group of architects, who were

shortly to take center stage in the world of Japanese architecture. While the

sources of the design are made clear by the inclusion in the exhibition of a model

of Le Corbusier's Unite d'Habitation (1952), for many observers this building

marked the historical moment that an authentically Japanese version of modernism

became plausible.

It is true that Mayekawa's legacy has been somewhat obscured by the increasingly

spectacular and indulgent Japanese architecture of recent decades. Even so, to

see his entire body of work gathered in one place plainly reveals the way its

innovative spirit, if not its formal ideas, have infused and influenced those

that followed.

|

|

|

|

|

Exhibition

images

© Hiroshi Matsukuma |

|

|

|

|

|

Kunio Mayekawa Retrospective

Exhibition |

|

Tokyo Station Gallery |

|

23 December

2005 - 5 March 2006 |

|

Hirosaki City Museum, Aomori Prefecture |

|

15 April

2005 - 28 May 2006 |

|

Niigata City Art Museum, Niigata Prefecture |

|

17 June 2005

- 16 August 2006 |

|

Fukuoka Art Museum |

|

22 September

- 5 November 2006 |

|

|

|

|