|

|

|

On Friedensreich Hundertwasser

Thomas Daniell |

|

|

|

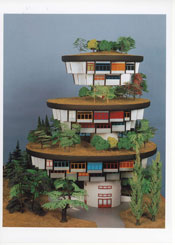

Friedensreich Hundertwasser

Highrise-Meadow-House, 1974

Production: Peter Manhardt

© Gruener Janura AG, Glarus/Switzerland |

|

One of the most interesting aspects of the recent retrospective of the work of Austrian artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser (1928-2000) was the inclusion of a number of his lesser-known early works. The young Friedrich Stowasser (Hundertwasser's real name) was a skilled figurative artist with a subtle and sensitive approach to color. These pieces provide a revealing contrast with the exuberance of the later paintings and prints that made Hundertwasser one of the most stylistically recognizable artists of the last fifty years. The exhibition shows his trajectory of increasing abstraction and intensification, with a simultaneous flattening of the picture plane and loss of perspective.

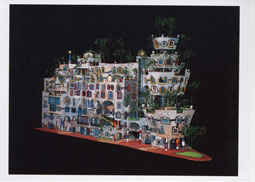

Also included were several of his architectural projects, most notably a huge model of the Blumau Hot Spring Village (1992), a collection of grass-roofed buildings buried in their undulating natural setting. Despite a complete lack of architectural training, Hundertwasser successfully designed and constructed a series of buildings beloved by the public and ignored by the architectural world. They were manifestations of his call for the transformation of buildings and cities via the reintroduction of nature, whether in the formal expression of the architecture or as living vegetation. Hundertwasser wanted the built environment to be a collective production of all its inhabitants (except perhaps architectural professionals themselves, whom he called "men of bad conscience who work with straight-edged rulers").

|

|

|

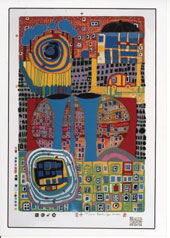

Friedensreich Hundertwasser

Blue Tears, 1997

© Gruener Janura AG, Glarus/Switzerland |

|

|

|

Friedensreich Hundertwasser

Hohe-Haine-Dresden, 1998

Production: Andreas Bodi

© Gruener Janura AG, Glarus/Switzerland |

|

|

It's absurdly generous of him to believe that the results would be anything but an anarchic mess; few people have the artistic talent or initiative to produce anything close to the charm and whimsy of Hundertwasser's own designs. The success of his buildings relied on a huge personal commitment. He was heavily involved in their actual construction. Indeed, despite the rhetoric, it is debatable whether he would allow his proposals for democratic design to include people with a significantly different aesthetic sense from his own -- people who actually like straight lines and muted colors, for example. Hundertwasser perhaps realized he was fighting a lost cause, and spent much of his later life living in a studio he built for himself in the New Zealand countryside, probably the closest you can get to a natural paradise without leaving the First World.

Yet however unreasonable his ambitions, there was no doubt about his sincerity in combating the enforced standardization of modernism. His manifesto demanding apartment dwellers the right to paint the areas around their own windows as a sign of their individual presence, or hyperbolic description of repetitive window patterns as "characteristic of concentration camps," become understandable in the context of a youth spent under Nazi rule and many family members murdered in the Holocaust. He envisaged societies in which everyone might have a place and purpose without any compromise of individual identity. Not unlike philosopher Karl Popper, another Austrian Jew who found temporary haven in New Zealand, Hundertwasser was warning us of the totalitarian conformity inherent to progressive social utopias. He wanted everyone to have the freedom to be different. His architectural designs may have trod a fine line between being wondrously childlike and simply being childish, but the ideals behind them will always be relevant. |

|

|

|

|

|