|

|

|

| On display at the Junzo Sakakura exhibition: original drawings, historic and present-day photos, and models of the architect's prolific body of work. |

|

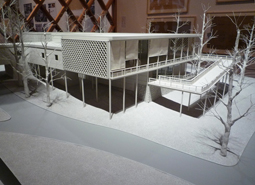

Model of the Japan Pavilion for the Paris Exposition, 1937. Its design was ridiculed by Sakakura's Japanese contemporaries until he received international acclaim for it. |

|

|

Junzo Sakakura was one of the first architects to incorporate elements from traditional Japanese design into 20th-century European modernism. An example is his design for the Museum of Modern Art in Kamakura. Currently the museum is commemorating the 40th anniversary of Sakakura's passing with a retrospective of his prolific career. The exhibition reexamines his broad-ranging works in architecture, city planning, interior and furniture design.

On the breezy, open-air lower level, stone sculptures by Isamu Nogichi occupy the center courtyard. A generous terrace opens out onto a pond of water lilies. There is a video, drawings and a large-scale plexiglass structural model of the museum. In two main rooms on the upper level, Sakakura's work is presented in chronological order through a well-balanced mix of historic and present-day photographs, original drawings and recently built models.

Born in 1901 in Gifu Prefecture, Sakakura majored in art history at Tokyo Imperial University, graduating in 1927. He then went on to study at the Ecole Speciale des Travaux Publics in Paris. He spent five formative years as an apprentice and then assistant in Le Corbusier's atelier. Stunning framed drawings from this period are on loan from the Fondation Le Corbusier. Shortly after leaving the atelier, Sakakura won the Grand Prix with his design for the Japanese Pavilion at the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne in Paris, 1937. Initially the design was ridiculed by his Japanese contemporaries, but after receiving international acclaim, he was praised at home. The pavilion -- a light, open, steel structure with glass and slate tile cladding -- exemplified the early International Style as interpreted by a Japanese architect. Sakakura was thereafter known as Le Corbusier's leading advocate in Japan.

A series of drawings and photographs on display feature Sakakura's work during World War II. In 1939 he was asked to plan a new Japanese settlement in Manchuria. The influence of Le Corbusier is apparent in a design that could be a direct descendant of Corbu's (unrealized) Ville Radieuse project from a decade earlier. Sakakura collaborated with furniture designers Sori Yanagi and Jean Prouve. In 1940 he helped his friend and former colleague, Charlotte Periand, come to Japan as an officially appointed industrial design advisor for the Ministry of Trade and Industry. Together they refined her design of a pre-fabricated, A-frame prototype house. The Japanese Navy shipped 60,000 square meters' worth to the frontlines.

Standardization and the ability to work with a shortage of materials enabled Sakakura to win the competition for the Museum of Modern Art in Kamakura, the first to be built in Japan after the war. The drawings on display show how he attempted to keep costs down: he chose short, steel freight trusses for the roof and clad the lower level in ooya, the domestic, lightweight lava rock famously used by Frank Lloyd Wright for the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo.

Sakakura established offices in Tokyo in 1947 and Osaka the following year. He continued to collaborate with other architects, including Kunio Maekawa and Junzo Yoshimura. One such collaboration was the International House of Japan, Tokyo (1955). Perhaps the best Japanese example of International Style, it is still well maintained today. In 1959 he helped oversee the construction of Le Corbusier's only work in Japan, The National Museum of Western Art in Ueno Park, Tokyo. That same year Sakakura completed a ski lodge in Hakuba, followed by the Toyo Rayon Headquarters (1962) and a series of civic projects in Hiraoka, Gifu and Kure. Some of the project displays include present-day photos, while others show only historic photos, suggesting that many of his buildings no longer exist.

The series "Sense of Promise" highlights Sakakura's most active period during the 1960s. In time for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, he was commissioned to design toll gates for the new Meishin Expressway, starting with the one in Ichinomiya. It must have been a futuristic notion in its time. His precast concrete prototype became the national standard. In that same year Sakakura was asked by the Japanese petroleum company Idemitsu Kosan to design a few filling stations. The company's number one requirement was to make each station distinctly different. Sakakura rose to the challenge, as can be seen in a crowd-pleasing photomontage of sweeping roofs and dramatic gestures in concrete. His office designed no less than 53 unique filling stations in a six-year period (1964-1970). The exhibition closes with a focus on Sakakura's largest commission, Shinjuku Station West-Gate Plaza and the Odakyu Department Store. Wall size photographs taken just after the project's completion in 1966 evoke the zeitgeist of an emerging Japan.

Sakakura responded to the dramatic changes, events and social issues of the Showa period. The caliber of his work is matched by the level of care that went into this exhibition. The curatorship is on par with what one would expect to find in world-class museums. For such an important exhibition, however, it was infuriating that absolutely no information was available in English, not even a handout at the front desk. (There were a number of other struggling foreigners visiting the museum on the same Saturday afternoon.) This lack of access made the exhibition feel exclusive and out-of-touch.

Sakakura wrote that more than members of any other profession, architects must respect human beings. He proselytized Corbu's concept of "unlimited growth." He dared to live and work abroad, to find collaborators in and outside of his field, and to bring new ideas back to his home country. Even by today's standards, he was well ahead of his time.

|