|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Down with Death

Christopher Stephens |

|

|

|

|

Shusaku Arakawa, Einstein Between Matter's Structure and Faintest Sound, 1958-59, The National Museum of Art, Osaka

Photo: Kazuo Fukunaga |

Death was constantly at the center of Shusaku Arakawa's career since he began making art at the end of the 1950s. More than a morbid fascination, the Great Leveler served as Arakawa's lifelong foe -- a force that he and his partner Madeline Gins refused to resign themselves to and continued to fight in the belief that what has long been viewed as human destiny might be "reversed."

Born in Nagoya in 1936, Arakawa first came to prominence as a member of the Neo Dadaism Organizers, a short-lived but highly influential avant-garde group formed by emerging artists such as Ushio Shinohara and Genpei Akasegawa in 1960. The following year, however, Arakawa relocated to New York, where he spent the rest of his life. While Yoko Ono and Takashi Murakami are now better known internationally, it's worth noting that in 1997 Arakawa became the first Japanese artist to hold a solo exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum.

|

|

|

Shusaku Arakawa, From the Series of Another Cemetery No.4, 1961, Itabashi Art Museum |

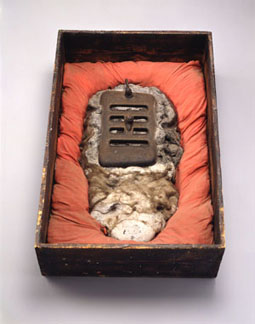

Consisting of only 20 items, the Funeral for Bioengineering to Not to Die exhibition, running through June 27 at the National Museum of Art, Osaka, is a historically significant event that reassembles the last works Arakawa created before leaving Japan. Originally presented in two solo shows at Tokyo galleries (one in 1960 which, opposed by the Neo Dadaism Organizers, caused him to break with the group, and one several months later in January 1961), the works share a common form and theme. Resembling coffins of various sizes, the dark-stained wooden boxes contain oddly shaped chunks of concrete, which are occasionally ornamented with strands or lumps of cotton, small stones, and metal parts from irons and other readymade objects, resting on a satiny cushion of purple or red cloth. In a few cases, a small stenciled arrow painted on the concrete points toward the bottom.

|

|

|

Shusaku Arakawa, Untitled Endurance No.2, 1958 (1986), Nagoya City Art Museum

All images © Shusaku Arakawa |

Only four of the works in the current exhibition have been positively identified as having appeared in the Tokyo shows. It is assumed, however, that among the many Arakawa pieces of the era titled Work, several were originally part of this group but due to their similar appearance were confused and mislabeled somewhere along the line. A glance at the original list of titles provides some insight into the potential meaning of the works, as all of them make reference to a noted scientist or scientific discovery -- i.e., The Wedding of Oppenheimer and Carlsson on a Cosmic Ray and Mr. So's Heart Transplant Using a Warm-Blooded Animal. With this in mind, one can't help but wonder which of the works might correspond to which title. One of the few that remains intact, Einstein Between Matter's Structure and Faintest Sound, centers on eight brain-shaped pieces of concrete, arranged in two rows of four. The upper group is indistinct and apparently fossilized, while the lower specimens grow progressively darker from left to right, perhaps suggesting a decline in function. Around these are balls of white cotton that are looser in construction and seem to be gradually cohering into grey matter. The other two works with scientific titles, Waksman's Chest (a reference to the discoverer of streptomycin) and Dr. Oparin's Prayer (a reference to the Russian biochemist who theorized that life began in the sea), are also notable for their use of brains.

Beyond bringing together a group of works that have been scattered around the country and, except for those few weeks in the early 1960s, were never shown in context again, the significance of the exhibition lies in the link it establishes between Arakawa's short period of activity in Japan and his nearly 50-year career in the U.S. Long before he began to speak in concrete terms of death as something "old-fashioned" and a curable "disease," Arakawa attempted, with these coffins, to bury the concept and suggest the unlimited potential of human activity.

To gain deeper insight into Arakawa's work, especially the architecture that became his main focus in later years, it's essential to visit the Site of Reversible Destiny, a philosophical amusement park he and Gins built in the small town of Yoro, Gifu Prefecture in 1995. Scattered across the hilly park are a series of concrete structures which, without a single flat surface, challenge and threaten to injure the visitor. Though the ultimate benefit of forcing someone along a winding passage with only enough space for one person at the top of a high wall -- or enticing them into the maze-like interior of a house furnished with bathtubs and beds that are bisected by walls -- might seem obscure, Arakawa clearly intended to help us break out of what he saw as dangerously comfortable routine behavior and retrain our bodies to overcome an unnecessary outcome.

Which makes it even sadder to learn, just as this article was being written, that this wholly original artist and thinker died in a New York hospital on May 19, 2010.

|

|

|

Christopher Stephens

Christopher Stephens has lived in the Kansai region for close to 25 years. In addition to serving as the editor of the now defunct magazine Kansai Time Out for many years, he has extensive experience as the translator of numerous exhibition catalogues for museums throughout Japan, and art and architecture books such as What's Gutai?, The Architecture of E.G. Asplund: 1885-1940, Salon to Biennial, World Architects 51, Miwa Yanagi: Windswept Women, Tomoko Konoike's Inter-Traveller, and Tadanori Yokoo's Tokyo Y-Junctions. |

|

|

|