|

|

|

| Misty hues and shaded tones convey the essence of Japan's Ama no Hashidate landscape in a painting (ca. 1506) by Sesshu Toyo, while Paul Cezanne's bird's-eye view of the Bay of Marseille from l'Estaque (ca. 1885) captures the strong light and vivid color contrasts of the Mediterranean coast. They are parallel stories reminding us that art and nature spring from the same source. |

In his book Like the Flowing River, Brazilian storyteller Paulo Coelho compiles myriad reflections on the transcendence of things, underscoring the alchemical view that each of us contains the universe. At a symposium held last month on the University of Tokyo's Komaba campus, architects Yoshiharu Tsukamoto and Akihisa Hirata joined author and University of Aberdeen social anthropologist Tim Ingold in a similar exercise, pulling together various disciplines to address the "fluid character of the life process" and how it relates to art and architectural design.

Moderated by professor Tami Yanagisawa of Nanzan University (whose recent research includes collaborating with Japanese neuroscientists to explore altruistic decision-making in religious thought and practice), the afternoon was a heady mix of ideas drawing upon the disciplines of phenomenology, metaphysics, philosophy, human ecology, and art history and practice, leavened at times by Tsukamoto's perceptive sense of humor and by Hirata's presentation of real design applications.

|

|

|

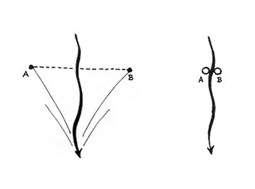

| Ingold's work in social and cultural anthropology argues against reductionisms that impede our full engagement with life. His integrative approach holds that buildings and monuments, viewed in the context of their surroundings, are more "archi-textural" than architectural. "There are no insides or outsides, no enclosures or disclosures, only openings and ways through." Boundaries are sustained only by the flow of materials across them. Figure reprinted by permission from Tim Ingold, Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description, Routledge, 2011, p. 84 |

In his keynote address, "Bringing Things to Life: Creative Entanglements in a World of Materials," Ingold explored the relations between people and the environments they inhabit, addressing what it means to make things, and the meaning of dwelling -- and by extension, what it means to be alive. Bringing things to life, he says, is not a matter of acting upon them but of "restoring them to the generative fluxes of the world of materials in which they came into being and continue to subsist."

|

|

|

| In practice we refer to the date a building was completed, but the story of creation does not end when the last mason or carpenter lays down his tools. The materials carry on -- aging, undergoing changes in response to their environment, acquiring character and sometimes breaking down. "Like life itself," says Ingold, "a real house is always work in progress, and the best that inhabitants can do is to steer it in the desired direction." Completion is an arbitrary point in a continuum. Photos © Susan Rogers Chikuba |

Arguing against Aristotle's hylomorphic model of creation, with its emphasis on matter (hyle) and form (morphe), Ingold refutes its lingering polarity in contemporary discussions of art and technology. He calls instead for "an ontology that assigns primacy to process over product, and to flows and transformations of materials over mere states of matter." "As practitioners," he maintains, "the builder, the gardener, the cook, the alchemist and the painter are not so much imposing form on matter as bringing together diverse materials and combining or redirecting their flow in the anticipation of what might emerge."

Hirata demonstrated this view in a presentation of his own design solutions based not on the rationalist "form follows function" approach, but on naturally occurring shapes, patterns, and "entwinings," and on relational lines of movement. The audience was introduced to a creative process that has conceived a chair from cabbage, a bridge from foam, a 3-D screen from knot theory, and buildings from trees. For an urban development competition whose organizers believed they needed a symbolic tower -- yet another monolith -- he proposed instead an open structure distinguished not by verticality but by its terrain-hugging continuity, begging the very question of what an architectural symbol is or can be.

|

|

|

"Knots yield fascinating surfaces," says Hirata. His Animated Knot screen installation, designed to showcase Canon's imaging technologies, began as a simple sketch of tangled lines. This was reproduced in three dimensions as a steel frame 20 meters long, 10 meters wide, and 6.5 meters high, then covered with zippered elastic membranes. The screen itself became a continuum in which, and through which, one could directly experience projected light.

Image (left) © akihisa hirata architecture office; photo (right) © Nacása & Partners Inc.

|

|

|

|

Hirata sees the living world as a fabric of tangled orders, from micro-scale proteins to the vast expanse of a rain forest. Coil, a private residence of his design, connects loosely layered spaces with a helical staircase wrapped, vine-like, around three structural columns.

Image (left) from Tomitake Tsukihara and Hiroaki Sakai, Tanpakushitsu no Sugata, Katachi to Sono Hataraki, Osaka University Press, 2001; photo (right) © akihisa hirata architecture office |

Tsukamoto furthered the meditation on questions central to philosophy and art practice by addressing "architectural behaviorology." Likening architects to behavioral scientists who study contingency relations and then apply that knowledge to engineer beneficial technologies, he suggested that a building's construction has already begun years prior to a client's initial inquiry. "The building, or elements of it, already exists in the future occupantsf minds before they ever come to see us," he explains. "We begin a new project by fleshing out the five years before their decision to build, as well as the ongoing life of the place after its completion."

In other words, the purpose of a building is a story, or a series of stories, about what its inhabitants want it to do. The story runs ahead of itself, so giving shape to it -- bringing it to use -- is a process of drawing past occurrences into the present. The architect, as listener, finds in the unfolding narrative essential traces or lifelines for guidance. Space, then, is a means of bringing multiple stories together, of enacting a narrative. Is it any surprise that "narrate" comes from gnarus, the proto-Indo-European root for "knowing"?

Lao Tzu famously said, "Walls with windows and doors form the house, but the empty space within is its essence." When such powerful wellsprings of thought trickle out from the high towers and closed walls of academia to merge with the mainstream building process, architecture will become very interesting indeed.

|

|

"The challenge is not how to make spaces, but how to create relational bundles of potential."

-- Akihisa Hirata (left)

"The architect's task is to identify the delight that is already there in the life or intent or surroundings or history of the place, and create a channel for it to be encountered more often."

-- Yoshiharu Tsukamoto (right) |

|

|

|

Tsukamoto's home and atelier is all about permeability of space, with public and private areas demarcated gently and the whole suffused with light.

© Atelier Bow-Wow |

|

|

Foam was Hirata's inspiration for his proposal of "breathing architecture" -- a bridge spanning the 125-meter mouth of Love River in Kaohsiung, Taiwan and integrating the city's close relation with the sea.

© Kuramochi + Oguma

All excerpts and images are reprinted with the permission of the authors and copyright holders, or are held in the public domain.

|

|