|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Clothing Exposed: Hiroshi Sugimoto at the Hara Museum

Lucy Birmingham |

|

|

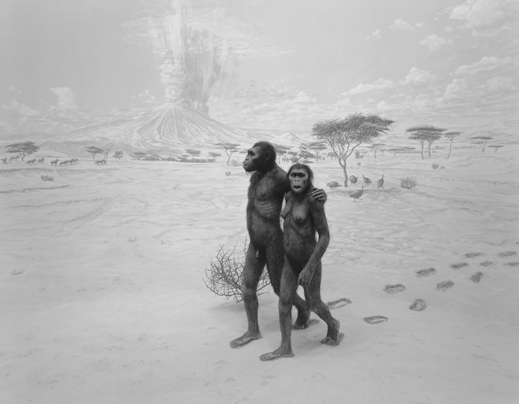

| Earliest Human Relatives, 1994, gelatin silver print, 64.7 x 89.5 cm. |

Hiroshi Sugimoto, the art photographer, designer, sculptor, architect and aspiring mathematician, has now taken on clothing -- to strip away and expose its naked truths. From Lucy, the three-million-year-old hominid, to a mélange of designs by modern-day fashion icons, "Hiroshi Sugimoto: From naked to clothed" (at the Hara Museum in Tokyo until July 1) reveals the why's of dressing. Is it provocative? Not really. Beautiful? Oh yes, with Sugimoto's perfectionist panache. He even unveils his signature sense of irony and humor in the engaging descriptions.

Henry VIII and His Six Wives greets visitors as they enter the museum. It's a tiny, elegant display of Sugimoto's long interest in photographing wax figures of the famous and infamous. Here, Henry shows off his royal robes and the authority they represent. Clothing is indeed powerful.

The black-and-white wax figure photo series continues down the hallway. Marie Antoinette, Queen Victoria, Rudolph Valentino and Mae West, all from celebrated wax museums, offer an historic Western look at fashion. They are paired with another of Sugimoto's photo passions: dioramas.

Neanderthals and Cro-Magnons model their wearable animal hides; actors in a Hollywood version of Spartacus don combat gear a la Roma; and a scene from Europe during the plague shows 14th-century "protective" wear reminiscent of the white body suits and masks of radioactive Fukushima. Like his wax figure photography, Sugimoto's dioramas are weird and wonderful, shedding a sublime light on the recreated scenes he discovered at the Museum of Natural History in New York City in 1974.

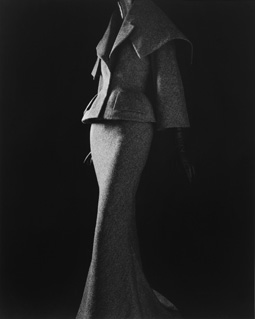

Step into the first-floor gallery and you face the supreme 20th-century Western fashion statements of Elsa Schiaparelli, Yves Saint Laurent, Andre Courreges, Cristobal Balenciaga, John Galliano, Maurizio Galante, Gabrielle "Coco" Chanel, and Alix Gres -- and their restyled Sugimoto versions.

The illusion continues on the second floor with Sugimoto's nod to Japanese brand designers and their "burst" upon the Paris Collection shows of the 1970s and 1980s. Yohji Yamamoto, Issey Miyake, and Rei Kawakubo represent that remarkable generation of newcomers with geometric shapes and materials worked in previously unimagined ways.

An actual Elsa Schiaparelli dress in gorgeous velvety reds is displayed on the third-floor stairs. But it becomes startlingly clear that Sugimoto's black-and-white photographic version has more appeal. The combination of lighting, camera lens, and monochrome printing technique has beautified the original clothing. "The photograph does not capture reality," Sugimoto says. "It captures what the photographer perceives . . . The lens lies."

Other visual commentaries on clothing include paintings from his private collection and historical Japanese patterns and costumes.

The exhibition is a virtual timeline of the evolution of the human figure, naked and clothed, with a focus on history -- like much of Sugimoto's work. "Rather than live at the cutting edge of the contemporary," he says, "I feel more at ease in the absent past."

Along with his mainly black-and-white images, Sugimoto's heavy wooden 19th-century-style, eight-by-ten-inch view camera is a clear testament to his preference for things of the past. This type of camera was often used by Ansel Adams and other photographers working in the landscape tradition of the American West. Long exposures using all natural light, a Sugimoto trademark, are enabled with a dense (16x) neutral-density filter attached to the lens.

|

Stylized Sculpture 003 (Rei Kawakubo 1994), 2007,

gelatin silver print, 149.2 x 119.4 cm.

Dress: collection of the Kyoto Costume Institute.

|

"Black-and-white photography is more difficult and more challenging," he says. "There is no digitization or computer involved. It's traditional, paper-based, using silver and chemicals. You can do many gimmicks using the computer. But the final product using the traditional method still creates better quality. People think that making the photography process easier is progress. It is the other way around. It's not progress. My type of method still makes a good picture," he explains. "As an example of this, the quality of the 12th- and 13th-century painters of the Renaissance was very, very high. Then later, maybe the quality of the brush got better and the process became easier. But the quality of the painting is not as good. It was better in harder times. Technology weakens the human spirit."

In 1970, at the age of 22, after graduating from Rikkyo University in Tokyo with a degree in economics, Sugimoto left Japan "as casually as if deciding to stay the night in a mountain temple," he writes. He traveled through the Soviet Union and Europe and settled in Los Angeles, where he studied photography at the Art Center College of Design because, according to his bio, "he needed a visa and photography was the easiest department in the college." There he received a BFA in 1972.

It wasn't until Sugimoto moved to New York City in 1974, he says, that he became seriously interested in art. It was there that he discovered the contemporary art scene. He was interested in the Minimalist and Conceptual movements popular at the time, but decided that photography, although a "second-class citizen in the fine art world," offered a more unique structure.

During the very beginnings of his photography work he supported himself as a carpenter, a trade he'd learned as a young man. Then, with his interest in objects of the past, he established a small antiques business with his late wife in 1979, buying works in Japan to be sold in New York. It was through this business that he developed a remarkable talent for detecting quality and a deeper understanding of Eastern and Western aesthetics. By the mid-80s, the business, dealing largely in Japanese religious art, became so successful that it allowed Sugimoto to concentrate wholly on his photography work with little worry about sales.

After 30 years based in New York City, Sugimoto became an established art photographer with a strong following. But it wasn't until his three-decade retrospective at Tokyo's Mori Art Museum in 2006 that he was recognized in Japan. Now he is in constant demand worldwide, living and working in both Tokyo and New York. A show of his new objects and sculptures at the Pace Gallery in New York last fall was sold out on opening night.

What will Sugimoto come up with next? No doubt it will be a fresh light on something clothed in history.

|

|

|

| Stylized Sculpture 011 (John Galliano 1997), 2007, gelatin silver print, 149.2 x 119.4 cm. Dress: collection of the Kyoto Costume Institute. |

|

Stylized Sculpture 008 (Yves Saint Laurent 1965), 2007, gelatin silver print, 149.2 x 119.4 cm. Dress: collection of the Kyoto Costume Institute.

|

All images © Hiroshi Sugimoto; courtesy of Gallery Koyanagi

|

|

|

|

Lucy Birmingham

Lucy Birmingham has been based in Japan for about 25 years and is now the Tokyo-based reporter for Time magazine. She has also written for Newsweek, Bloomberg News, Architectural Digest, The Boston Globe, Artinfo.com, Artforum.com, and ARTnews, among other publications. As a photojournalist her work has appeared in The New York Times, Business Week, Forbes, Fortune, U.S. News and World Report, and A Day in the Life of Japan. She is also a scriptwriter and contributing editor at NHK, Japan's public broadcaster, and has published several books including Old Kyoto: A Guide to Traditional Shops, Restaurants, and Inns. |

|

|

|