|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

The Allure of the Collection: Thirty-five Years of the National Museum of Art, Osaka

Christopher Stephens |

|

|

|

|

| Yoshitomo Nara, The Longest Night, 1995 (© Yoshitomo Nara, courtesy of the artist) |

|

Kumi Machida, Snow Day, 2008 (© Kumi Machida, courtesy of Nishimura Gallery) |

Though a collection exhibition might lack the appeal of a specially curated show on a given theme, it is bound to include a few highlights and discoveries. And so it is with The Allure of the Collection, a show (running through June 24) that is designed to commemorate the 35th anniversary of the National Museum of Art, Osaka. Featuring some 350 items selected from a total of over 6,500 works, the exhibition focuses on modern and contemporary expressions by leading Western figures such as Marcel Duchamp, Andy Warhol, and Gerhard Richter, and a roughly equal number of Japanese artists spread across two floors, one of which is devoted solely to photography.

Japan's network of national art institutions is made up of three museums in Tokyo (the National Museum of Modern Art, the National Museum of Western Art, and the National Art Center) and two in the Kansai region (the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, and the National Museum of Art, Osaka), with combined holdings of well over 30,000 works. The Osaka facility opened in 1977 in a building that had been used as a museum pavilion at the Osaka Expo in 1970. At the time, it seemed as if the city was destined to sprawl further northward toward the Expo site, but by the turn of the 21st century this "new town" area had grown old and was no longer much of a draw. This led the museum to relocate in 2007 to the Nakanoshima area of central Osaka, to a new underground structure designed by César Pelli. In light of the tremendous success of the Yayoi Kusama exhibition there, which drew a record 200,000 visitors over its three-month run earlier this year, this seems to have been a wise choice.

Though the majority of the Osaka collection dates from the postwar era, there are also several paintings by early pioneers like Tsuguharu Fujita (also known as Leonard Foujita) and Yuzo Saeki who moved to Paris in the teens and '20s, respectively, and conveyed the latest trends in modern art to their peers in Japan. With his bowl haircut, Harold Lloyd glasses, and a tattoo of a wristwatch on his left arm, Fujita was the embodiment of a bohemian painter, and is remembered for his many pictures of nude women and cats. Saeki, meanwhile, was heavily influenced by Utrillo and the Fauvists, and concentrated primarily on Parisian cityscapes until his premature death at 30 of tuberculosis.

|

Naoya Hatakeyama, Blast #5707, 1998 (© Naoya Hatakeyama, courtesy of the artist)

|

A line can be drawn from this generation, born in the late 19th century, to transitional figures such as Jiro Yoshihara, who when seeking Fujita's advice early in his career was derided for his imitative style. Taking this criticism to heart, Yoshihara moved away from Surrealism and embraced abstraction after the war. Then, in the mid-'50s, he exhorted the group of young artists who had assembled around him to discover their own original styles, and with them formed the Gutai Art Association. While Yoshihara's painting, which continued to evolve until his death in 1972, was overshadowed by the group's radical performance-style approach, Gutai is probably the most renowned Japanese art movement in the world. Along with one of Yoshihara's later works -- a large white circle on a black ground that appears to have been painted in a single calligraphic stroke, but was actually painstakingly assembled out of a buildup of minute lines -- Gutai is represented in the exhibition by Kazuo Shiraga, Atsuko Tanaka, and others.

The presence of the Mono-ha (literally "school of things") movement of the late '60s and early '70s is also strong. The origin of the loose-knit group is said to date to Nobuo Sekine's 1968 sculpture Phase - Mother Earth, which consisted of a huge cylinder of earth towering over a hole of the same dimensions in a park in Kobe. This work in turn led the Korean-born, Japan-based artist Lee Ufan to develop an artistic philosophy that championed the use of natural and industrial materials such as stone, wood, glass, and steel with a minimum of human intervention. Despite its visual simplicity, the group's work remains rather obscure but has clear links to Minimalism and Land Art, and at the height of its popularity in the early '70s, Mono-ha held such sway in Japan that it was virtually impossible to paint or attempt any other type of figurative expression.

|

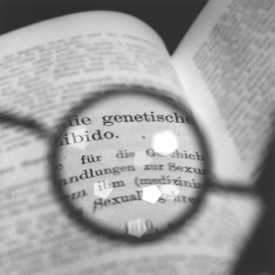

Tomoko Yoneda,

Freud's Glasses -- Viewing a Text by Jung II, 1998

(© Tomoko Yoneda, courtesy of ShugoArts)

|

It is also encouraging to see that work by overlooked iconoclasts like Tetsumi Kudo and Mieko (formerly Chieko) Shiomi has been included in the exhibition. Initially associated with the Dada-inspired Anti-Art movement, Kudo relocated to Paris in 1962 and remained in France for the next 25 years, staging a series of bizarre happenings and making sculptural landscapes and birdcages -- filled with wilted plastic flowers, phalluses, and brains -- that today seem especially prescient for their recurring references to radiation and ecological destruction. Influenced by John Cage and other contemporary composers, Shiomi formed the improvisational trio Group Ongaku with Takehisa Kosugi and Yasunao Tone in the early '60s, before moving to New York to take part in Fluxus on the invitation of the group's leader, George Maciunas. Her conceptual music and visual art pieces often called for participation by the audience and other artists in performing simple actions based on written instructions, and reflect the "intermedia" trend of freely mixing forms and genres that emerged during that period.

As with any show of this size, it is easy to leave the museum with a muddle of images, none of which is particularly memorable. One way to deal with this is to forego the "usual route" and come up with a unique path through the displays. This might involve a certain amount of backtracking and retracing of one's steps, but deciding, for example, to trace the history of Japanese painting from Tsuguharu Fujita to Makoto Aida, or choosing a theme like women artists or Kansai vs. Kanto, promises a better viewing experience. After all, the real curator is you.

|

|

Christopher Stephens

Christopher Stephens has lived in the Kansai region for close to 25 years. In addition to serving as the editor of the now defunct magazine Kansai Time Out for many years, he has extensive experience as the translator of numerous exhibition catalogues for museums throughout Japan, and art and architecture books such as What's Gutai?, The Architecture of E.G. Asplund: 1885-1940, Salon to Biennial, World Architects 51, Miwa Yanagi: Windswept Women, Tomoko Konoike's Inter-Traveller, and Tadanori Yokoo's Tokyo Y-Junctions. |

|

|

|