|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Gutai: The Kansai Avant-Garde Group Finally Arrives

Christopher Stephens |

|

|

|

|

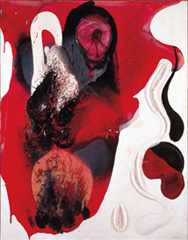

Jiro Yoshihara, Red Circle on Black, 1965 (courtesy of Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art)

|

|

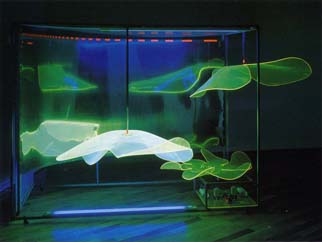

Saburo Murakami, Work, 1958 (courtesy of Kitakyushu Municipal Museum of Art) |

Like butoh dance and Japanoise music, the avant-garde approach of the Gutai Art Association has proved to be more popular abroad than it has at home. Over the last 20 years in particular, the Kansai-based group has been showcased in a variety of exhibitions in Europe, and a large-scale retrospective is to be held at the Guggenheim Museum in New York next February. This year marks the 40th anniversary of group leader Jiro Yoshihara's death and Gutai's subsequent breakup, and the Gutai: The Spirit of an Era exhibition (at the National Art Center, Tokyo through September 10) marks the first time that the group's entire 18-year career has ever been presented in Tokyo.

Gutai was formed in 1954 by 17 artists who gathered around Yoshihara (1905-72), the wealthy president of a vegetable-oil wholesaler who had also been an established figure in the Kansai art world since before World War II. With an unwavering vision, Yoshihara demanded nothing less than total allegiance and originality from his young charges. He was also ahead of his time in seeking international recognition for Gutai through the publication of a bilingual magazine that was sent to artists, critics, and museums around the world.

Today, Gutai is often credited with inventing performance art through a series of events it held in unusual places like city parks and theater stages. This assessment is largely based on works like Saburo Murakami's "paper breakthroughs," in which he burst through fusuma-like screens covered with sheets of kraft paper; Kazuo Shiraga's Challenging Mud, in which he wrestled and rolled around half-naked in a container full of mud; and Shozo Shimamoto's paintings made by smashing bottles of paint against the canvas. The truth is inevitably a bit more complicated. Though the artists certainly did these things, they were in many cases designed exclusively for the benefit of the media rather than the general public, and as the only extant record of such actions is a few photographs (some of which were posed) and contemporary newspaper reports, their true nature remains unclear.

Another important distinction to make about Gutai is that while the artists initially focused on experimental and interactive works, these only accounted for the first few years of the group's career. In 1957 Gutai was discovered by the French critic Michel Tapié, who saw the group as part of the wide-ranging Art Informel trend that he believed represented a decisive break with the past. Tapié's devotion to Gutai and his ceaseless efforts to promote its work in the West were vital to the group's international standing. But in his secondary role as art dealer, he also pressed Yoshihara for more paintings (as they would be easier to export and sell to foreign buyers), and ultimately curbed the group's more experimental tendencies.

|

|

|

| Sadamasa Motonaga, Work, 1960 (courtesy of Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art) |

|

Takesada Matsutani, Work '65, 1965 (courtesy of Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art) |

In the early sixties, Yoshihara began to sense that the Art Informel style had lost much of its appeal and that something had to be done to save Gutai. His solution was to recruit a younger generation of artists who were influenced by current trends such as pop, kinetic, and technological art. Yoshihara also established the Gutai Pinacotheca, a private museum and headquarters for the group in three refurbished storehouses in Osaka's Nakanoshima district, which attracted visiting dignitaries from the art world like John Cage, Jasper Johns, and Robert Rauschenberg. It was also around this time that Yoshihara managed to set aside his role as leader and redefine himself as an artist with a series of massive two-colored (usually black-and-white or red-and-black) canvases depicting a large circle that had seemingly been applied with a single calligraphic stroke of the brush.

Gutai's work as a group culminated with a series of performances involving materials like robots and fire engines at the Japan World Exposition held in Osaka in 1970, an event which itself was viewed as the zenith of the nation's economic growth and industrial development. To some, it appeared as if Gutai had successfully updated its original revolutionary approach, but to others the idea of Gutai participating in what was essentially a government-sponsored commercial for Japan signaled the end of an era. Some of Gutai's older members were also growing tired of Yoshihara's iron-fisted control -- Murakami Saburo, for example, submitted a letter of resignation in 1971, only to have it immediately rejected. After Yoshihara's abrupt death in 1972, however, there seemed to be no way forward and the members voted to dissolve the group.

Due in part to the historical rivalry that exists between the eastern Kanto and western Kansai regions of Japan, Tokyo critics and viewers tended to dismiss Gutai as overly flippant or lacking in artistic significance, which explains why a major retrospective has been so long in coming to the capital. Though there are plenty of works in Gutai: The Spirit of an Era (organized by renowned Gutai expert and National Art Center curator Shoichi Hirai) that seem rather dated or not particularly inspiring, the show provides a fascinating and thorough examination of this pioneering group while reflecting a variety of important trends in postwar art. By the end, though, the viewer comes away thinking mostly of Jiro Yoshihara, an artist whose uncanny insight and limitless capacity for reinvention have kept us preoccupied for several decades with his greatest creation -- the Gutai Art Association.

|

|

Minoru Yoshida, Just Curve '67 Cosmoplastic, 1967 (courtesy of Takamatsu City Museum of Art)

|

|

|

Christopher Stephens

Christopher Stephens has lived in the Kansai region for close to 25 years. In addition to serving as the editor of the now defunct magazine Kansai Time Out for many years, he has extensive experience as the translator of numerous exhibition catalogues for museums throughout Japan, and art and architecture books such as What's Gutai?, The Architecture of E.G. Asplund: 1885-1940, Salon to Biennial, World Architects 51, Miwa Yanagi: Windswept Women, Tomoko Konoike's Inter-Traveller, and Tadanori Yokoo's Tokyo Y-Junctions. |

|

|

|