|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Fine Prints: Kumi Sugai and Takesada Matsutani at the Ashiya City Museum of Art & History

Christopher Stephens |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Kumi Sugai, Diable Rouge (1955, lithograph) |

|

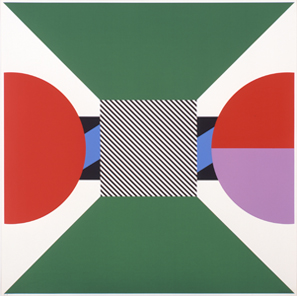

Kumi Sugai, Festival (1973, silkscreen) |

It is not immediately clear why Kumi Sugai and Takesada Matsutani are paired in print works, the exhibition currently at the Ashiya City Museum of Art & History, except for the obvious fact that both artists are closely associated with the print medium. This subtle curatorial approach turns out to be a winning formula, however, as viewers are left to search for similarities and form links of their own.

Sugai, who died in 1996, was nearly 20 years older than Matsutani, a still vibrant creative presence today at the age of 76. Both were born and raised in the Kansai region of western Japan -- Sugai's family eventually settling in Ashiya, Matsutani's in the neighboring city of Nishinomiya. Both suffered serious illnesses as a child; Sugai was bedridden for nearly two years with valvular heart disease and Matsutani was in and out of the hospital for eight years with tuberculosis. But perhaps more importantly, both received formative training in Nihonga (Japanese-style painting).

Among the first to recognize Sugai's talents in the late '40s was Jiro Yoshihara (1905-72), a well-established avant-garde painter who several years later formed the Gutai Art Association. In the '50s and early '60s, Gutai (also based in Ashiya) came to represent the cutting edge of art in Kansai and is today regarded as one of the pivotal chapters in Japanese modern art history. Matsutani joined the group in 1959 on the recommendation of Gutai member Sadamasa Motonaga, and continued to show his work in Gutai exhibitions until the group disbanded in 1972.

In 1952, after receiving several awards in Japanese art competitions and working as a designer at Hankyu Railways and the Asahi Shimbun newspaper, Sugai moved to Paris, where he remained for most of his life. There he discovered printmaking, initially drawing on demons and other creatures from Japanese folk tales for motifs and later adopting a calligraphic approach. But in time, after being exposed to the wide range of cultures and artistic traditions in Europe, Sugai changed tack and declared, "I no longer have any measly notions about being Japanese or Asian. Before my Japanese background, I assert the larger entity of myself as an individual." This new perspective helped the artist arrive at a unique style, free of any overt cultural references.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Takesada Matsutani, Propagation-Line (1970, silkscreen) |

|

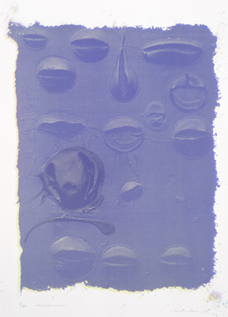

Takesada Matsutani, Propagation-200 (1974, photo silkscreen)

All works shown are from the collection of the Ashiya City Museum of Art & History. |

Matsutani has lived in France since 1966, when he was awarded a French government scholarship in the First Mainichi Art Competition. His early work in Gutai was distinguished by the use of what at the time was the new material of vinyl glue, which he dripped over the canvas and used to create large bubble-like membranes that resembled microscopic organisms. But the impact of a Dada retrospective ("they had already done everything there was to do") he saw in Paris not long after arriving in the city discouraged him from pursuing this approach any further. Searching for a new direction, he came across S.W. Hayter's Atelier 17 studio, and after studying for several weeks with the noted British printmaker, Matsutani returned to his more conventional roots, depicting organic forms in two dimensions and focusing on composition instead of relying on the element of chance, which had been such a critical part of his Gutai-era work.

Though printmaking had flourished in Japan in the Edo and Meiji periods, it had never been accepted as a genuine form of artistic expression. This changed in the 1950s with the emergence of the Mingei (folk art) artist Shiko Munakata, who won a series of important prizes at international festivals including the Venice Biennale and the first installment of the Tokyo International Biennial Print Exhibition in 1957. Around the same time, Andy Warhol and other Pop artists began experimenting with silkscreen and closed the gap between painting and printing. Sugai's entry into the field happened to dovetail with this emerging movement, and Matsutani arrived at the peak of Pop. In the late '60s, all signs of the hand disappeared from printing as bold primary colors, geometrical shapes, and symmetrical compositions reminiscent of commercial design took hold. This trend is also evident in the Ashiya exhibition, as Sugai and Matsutani's work of the late '60s and early '70s came for a short time to look so similar as to be nearly indistinguishable. But before long they had again diverged as Sugai evolved toward eye-catching graphics, including a particularly stunning zodiac series, and Matsutani incorporated photographs of deflated glue organisms and more abstract images. Matsutani also added materials to the surface of his works, integrating two- and three-dimensional expressions and various techniques from his past.

Filling two large rooms, the print works exhibition offers a fresh look at two artists who have perhaps not received their due, in part because they chose to stay away from Japan for so long and in part because of their choice of medium. It also reminds us that Ashiya, a wealthy city of about 90,000 people located between Osaka and Kobe, has produced a substantial number of highly regarded artists, among them members of Gutai and the influential Ashiya Camera Club (1930-42). The nagging question that the show fails to answer, however, is: Did Sugai and Matsutani, who shared so much for over three decades, ever actually meet or exert a direct influence on each other?

|

|

Christopher Stephens

Christopher Stephens has lived in the Kansai region for over 25 years. In addition to appearing in numerous catalogues for museums and art events throughout Japan, his translations on art and architecture have accompanied exhibitions in Spain, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, South Korea, and the U.S. His recent published work includes From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and Gutai: Splendid Playground (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2013). |

|

|

|