|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Monozukuri Mania at Miraikan (and Elsewhere)

Susan Rogers Chikuba |

|

|

|

|

|

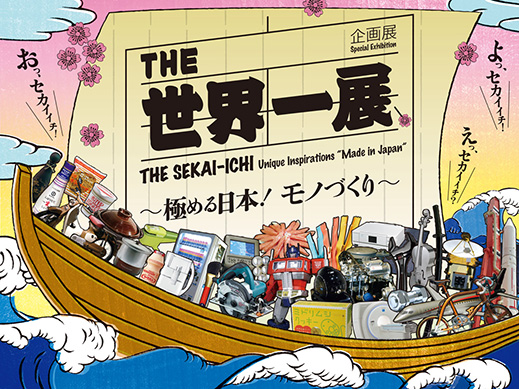

The ambitious Sekai-Ichi show at Miraikan exhibits more than 200 products and technologies, addressing Japan’s production strengths from angles like knowledge sharing, resourcefulness, and the omotenashi service mentality. |

As the January 2014 issue of Artscape Japan goes online, no less than four exhibitions in Tokyo are showcasing monozukuri -- the Japanese approach to the art (and science) of making things. Through January 13, the National Museum of Modern Art presents collaborations between regional manufacturers of traditional crafts and commercially successful designers in Product Design Today: Creating "Made in Japan". Through February 23, the same museum's Crafts Gallery shows works of active Living National Treasures in From Crafts to Kogei, claiming with its bilingual wordplay that "kogei" (crafts) is a genre unto itself, with no need for translation. At the National Art Center through January 26, the 16th annual Domani exhibition examines the house of the future as conceived by 52 Japanese architects and artists who studied abroad under the auspices of the Agency for Cultural Affairs. Finally, at the National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation (Miraikan) through May 6, over 200 products and technologies have been brought together in The Sekai-Ichi: Unique Inspirations "Made in Japan".

That's a lot to take in, but the themes alone tell much about current events. The alignment of focus at four national venues is less coincidental than indicative of a mood that's been gaining momentum since the Liberal Democratic Party regained power in December 2012. As the education minister calls for an expanded civics curriculum that boosts pride in things Japanese by fostering respect for national symbols, traditions, and the oft-extolled "unique" aspects of Japanese culture, we see in this sampling of shows presentations on innovation through collaboration, respect for craft and its preservation, applied study, and the pursuit of perfection -- elements that are as Japanese as sushi and Shinto.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| For the gods, only the best: Each time the Shikinen Sengu ceremonies of reconstruction at Ise Shrine take place (an event dating back to 690 and observed once every 20 years), even the carpenter’s tools used in the process are created anew. This way, the art of toolmaking is preserved and itself becomes a kind of spiritual mission. Left photo courtesy of Miraikan |

The Miraikan show, whose 200-plus items span centuries of Japanese industry, is the most ambitious in scale. It opens with an exhibit on Shikinen Sengu, the 1,300-year-old rite of renewal carried out every two decades at Ise Shrine (a key sanctuary within the Shinto faith), and concludes many galleries later with a presentation on omotenashi (Japanese-style hospitality). This is another theme that's been getting a lot of airtime in Japan of late -- and not only because of record-setting inbound tourism figures, or Cool Tokyo ambassador Christel Takigawa's impassioned use of the word in her final-stage bid presentation to the IOC last September. (Her speech, delivered in French, went viral domestically, prompting the term's selection last month as one of Japan's top ten buzzwords of 2013.) Omotenashi's recent advent in kulturspeak in fact goes back to late 2012, when the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) launched a business model and company ranking system based on the concept and designed to foster value-added services and conscientious management. As a result the term has become a new byword of "made in Japan" promotions, turning up everywhere from corporate slogans to product campaigns and exhibitions like this one, where some of the METI-ranked case studies are introduced.

|

|

|

|

|

|

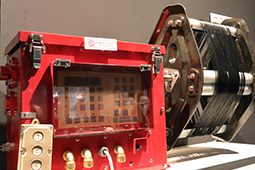

| Invented in Japan, commercialized in 1971, improved in close consultation with fishermen, and now exported to 30 countries, the contraption at left is an automatized jigging machine that revolutionized squid fishing. The textureful image at right appears to be a fine woodcarving, perhaps even lasercut, but in fact it’s a two-dimensional scanned image by a little-known product called the Photomap Scamera. |

Just as monozukuri has a semantic reach that goes beyond the mere making of things to include constant tinkering with the production process itself, omotenashi likewise brings nuances of diligence and harmony to the notion of hospitality. Both are about getting the job done well, with an attitude that's mindful of the user or larger community. Such concerns, which branch out into ideas about sustainability, resourcefulness, perfection, miniaturization, and so on, are probed again and again in the Miraikan show, across exhibits as weird and wonderful as equipment for hauling in squid on the high seas, product packaging for fermented natto beans, microsurgery needles, high-performance sports apparel, vending machines that eject both hot and cold canned drinks, and the art of repairing broken pottery. Many of the curators' choices, and the premises given for why the items are unique in the world market, are head-nodding if not eye-opening in their revelations; others -- like the first domestically produced lightbulbs, for example -- have more to do with achievements made on the way to innovation than any original contribution. A few displays teeter on the edge of navel-gazing, but all told, there's no doubt you'll leave the show having learned something you never knew about Japanese ingenuity.

|

|

|

|

|

|

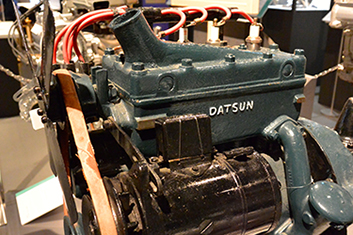

| A milestone in the history of compact-car manufacture, the Datsun Model 7 (1935) was the first engine assembled almost entirely from parts made in Japan. Four decades later, the Honda Civic CVCC engine (1975) became the world’s first to clear the stringent emissions standards of the 1970 Clean Air Act. Right photo courtesy of Miraikan |

Miraikan is a popular destination for school trips, so its exhibits are designed to appeal to visitors of all ages. This makes it a great place for family outings. Panels placed here and there at the Sekai-Ichi show prompt viewers to imagine the person or people who created the items on display, to look carefully from different perspectives, and to consider how you yourself might use the products. In addition, the museum's ever-circulating "science communicators" and orange-vested volunteers are on the floor to answer questions and make things more accessible. In this learning-conducive environment, you might send your child off in search of the smallest technologies featured (a spring too tiny to be seen with the naked eye? the world's thinnest needle? a conductive fiber 1/700th the thickness of human hair?), or the largest (glass aquarium walls? a 5,300-kilogram Bridgestone tire? the 66-antennae telescope array in Chile?), while you take a moment to linger, say, at a sweet display of iconic car engines: the 1935 Datsun, 1967 Mazda Rotary, 1975 Honda Civic, and 1997 Toyota Prius.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ASIMO, Honda's humanoid spokesperson for enhanced mobility technologies and other robotics research, is a star attraction at Miraikan, where you can catch his dance moves and soccer skills twice daily. Regular demonstrations by museum staff also take place within the permanent exhibits. |

Because it's located out on Odaiba island in Tokyo Bay, a trip to Miraikan always feels like an excursion. While you're there, allow ample time for the permanent exhibits on space and sea exploration, the global environment, and bio-, nano-, and information network technologies. Also check the daily events schedule for the planetarium theater shows, appearances by ASIMO, and various floor presentations by museum staff.

For a really full day of exploration, Odaiba itself is like a macro display of the monozukuri spirit applied to creative urban engineering. What began as a group of manmade islands built for defense in the 1850s has been reshaped time and again: the area served for a while as landfill, then was retooled as a residential and commercial showcase for futuristic living (a project abandoned in 1995, with many of its developers going bankrupt in the aftermath of the economic bubble). It then evolved into the waterfront leisure and corporate/research zone it is today -- a series of wide-open campuses, linked by monorail and sprawling with amusement parks, shopping malls, company headquarters, and convention and research centers. (Miraikan is part of Tokyo Academic Park, a complex headed by the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology.) As Odaiba and its surroundings will be home to 21 of the 33 planned competition venues for the 2020 Summer Olympics, construction is gearing up once again. No doubt we'll be seeing many more "Japan brand" events here and elsewhere, as Tokyo prepares to welcome the world and strut its stuff.

|

|

|

|

Miraikan visitors are dwarfed by Geo-Cosmos, a near-real-time display of weather patterns across the globe, as captured by satellite.

Photographs are by Susan Rogers Chikuba, unless otherwise noted.

|

|

|

Susan Rogers Chikuba

Susan Rogers Chikuba, a Tokyo-based writer, editor and translator, has been following popular culture, architecture and design in Japan for 25 years. She covers the country's travel, real estate, hospitality and culinary scenes for domestic and international publications. |

|

|

|