|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Dreamcatcher: Koji Fukiya and the Hearts of Young Girls

Alice Gordenker |

|

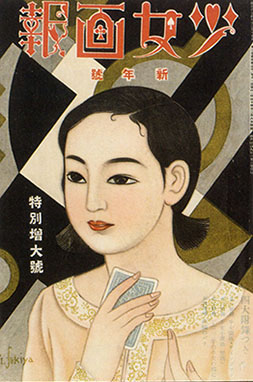

The period after World War I was a time of great change in Japan, not least for young women, who were suddenly afforded new freedoms and increased opportunities for education and employment. A host of magazines with titles like Shojo Gaho ("Girls' Illustrated") and Shojo Kurabu ("Girls' Club") arose to cater to modern young ladies who aspired to Western fashions and lifestyles. The most popular publications offered serialized novels, poetry, and tips for daily life, and were richly illustrated by talented artists.

One young artist who made his name in the pages of girls' magazines was Koji Fukiya (1898-1979), whose stylish, romantic images of beautiful young women still resonate with viewers today. Although not as well known as his contemporary Yumeji Takehisa, who also got his start illustrating women's periodicals, Fukiya was honored in 2011 with a large-scale retrospective held at the Sogo Museum of Art in Yokohama and the Kariya City Art Museum in Aichi Prefecture.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Koji Fukiya, cover of Reijokai magazine, September 1938. |

|

Koji Fukiya, cover of Shojo Gaho magazine, January 1933. |

Fortunately, we have another opportunity to view a significant number of Fukiya's works together, in a special exhibition at the newly reopened postal museum in Tokyo. The museum closed last August to make way for redevelopment in the downtown Otemachi financial district, where it was known in English as the Communications Museum. When it reopened on March 1 in the trendy Tokyo SkyTree complex, the facility took on a new English moniker: Postal Museum Japan. Through May 25, it is exhibiting more than 100 examples of Fukiya's work, including pen-and-ink drawings, paintings, poetry collections, and books and magazines.

If you're wondering why the show was organized by a museum devoted to postal history, it's because Fukiya's painting of a bride in traditional wedding kimono was featured on a wildly popular 50-yen stamp. Released in 1997 as part of the long-running Furusato ("Hometown") series, the stamp is still in high demand, particularly for use on the pre-addressed, pre-stamped reply postcards that are enclosed in wedding invitations. Many current Fukiya fans became acquainted with his work thanks to this stamp.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Koji Fukiya, Bride (1968), Fukiya Koji Memorial Museum. |

|

Hanayome ("Bride") 50-yen stamp (1997) from the Furusato series. Photo by Alice Gordenker |

Koji Fukiya was born in 1898 in the town of Shibata in Niigata Prefecture to very young parents who had just eloped. Life was hard and his mother, who was apparently a rare beauty, grew sickly and died when Fukiya was just 12 years old. Some scholars have suggested that the early loss of his mother accounts for the predominance in Fukiya's oeuvre of softly emotional depictions of women and girls. In any case, he was clearly at his best when portraying romantic images of fashionable young beauties.

|

|

|

|

|

Koji Fukiya, Grapes (1925), Fukiya Koji Memorial Museum.

|

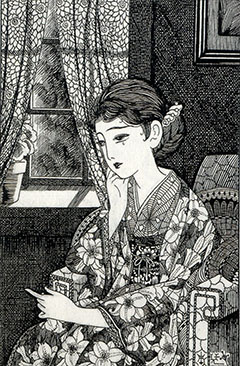

Fukiya came to Tokyo at the age 15 to apprentice with the Nihonga painter Otake Chikuha, who was also from Niigata. But his big break came later, when a friend introduced him to Yumeji Takehisa in 1920. Takehisa gave him a letter of introduction to the editor of Shojo Gaho, who invited him to submit illustrations. By the next year, he was doing the magazine's covers. He was also recruited to be the featured artist at Reijokai, which catered to a slightly older readership -- young women who had graduated from school but were not yet married.

Fukiya's illustrations were soon in high demand, appearing in a number of newspapers and magazines. He drew women with willowy figures, beautiful hair and big round eyes, and had a keen eye for fashion. Whether portrayed in kimono or Western dress, his young ladies always seemed to wear just what his readers most aspired to. He also wrote poetry, and in 1924 he published a sentimental poem called Hanayome Ningyo ("The Bride Doll"), about a beautifully dressed bride's emotions as she is about to leave girlhood behind for an uncertain future. The lines were later put to music by composer Haseo Sugiyama, and Fukiya's fame soared.

|

|

|

| Koji Fukiya, Mixed-blood Child with his Mother and Father (1926), Fukiya Koji Memorial Museum. |

|

Koji Fukiya, Woman Holding a Pomegranate (1927), private collection. |

|

|

|

|

|

Koji Fukiya, Troubles (1924), private collection.

|

Despite his successes as an illustrator and poet, Fukiya had not given up his dream of becoming a serious painter. To that end, he moved to Paris in 1925, working in a small atelier shared with several other Japanese artists. Several of the paintings he made in Paris were selected for prestigious exhibitions, including Mixed-blood Child with his Mother and Father, which was displayed at the Salon d'Automne in 1926. Painted just as Fukiya was working to develop his own style by combining elements of Japanese and Western painting, the work depicts a young boy with his Japanese mother and Western father. The mother is portrayed in kimono in front of an outdoor view done with Western perspective, while the blue-eyed father sits on a chair in front of a Japanese screen.

Unfortunately, many paintings from Fukiya's Paris period have been lost, surviving only as records in diary entries and photographs. One painting turned up unexpectedly in 1998, discovered by accident in a Paris warehouse. This is Woman Holding a Pomegranate, which Fukiya submitted to the Salon d'Automne in 1927. The whereabouts of another painting of a woman submitted at the same time are unknown. One can only hope it will turn up some day in someone's attic.

In 1929, Fukiya returned to Japan to deal with urgent family problems, thinking he would go back to Paris as soon as he had things sorted out. But the situation proved worse than he thought, and in the end, he was never able to go back. He returned to magazine illustration to pay off his family's debts, but after the Manchurian Incident in 1931 the country became preoccupied with war. Frivolity was discouraged and even censored, and throughout the war Fukiya had to adopt patriotic themes.

The war finally ended in 1945, but women's magazines changed, moving away from illustrations in favor of photographs. Fukiya turned to illustrating children's books, where he gained a new and loyal audience. He provided the illustrations for famous editions of both Japanese fairy tales and translations of Western children's stories, including Heidi, Sinbad the Sailor, and the tales of Hans Christian Andersen. Parents and children alike were captivated by his imaginative scenes and beautiful use of color. Whether in women's magazines or children's books, Fukiya had a rare talent for capturing in pictures the dreams and heartfelt aspirations of his audience.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Koji Fukiya, illustration from children's book Ningyohime ("The Fish Princess"), Kodansha, 1956. |

|

Koji Fukiya, dreamy in his early twenties.

All images courtesy of Postal Museum Japan, by permission of the lending institution. |

|

|

|

|

Shojo no akogare ("The Dreams of Young Girls") |

|

Postal Museum Japan |

| |

1 March - 25 May 2014 |

| |

Tokyo SkyTree Town Solamachi 9F, 1-1-2, Oshiage, Sumida-ku, Tokyo

Hours: 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. (last entry 5:00 p.m.). Closed 7 May; otherwise open daily during the exhibition period

Access: 1-minute walk from Tokyo SkyTree Station on the Tobu SkyTree Line

If you miss the exhibition, most of these works can be seen at the museum built in Fukiya's honor in his hometown:

Koji Fukiya Memorial Museum of Art

4-11-7 Chuo-cho, Shibata City, Niigata

Phone: 0254-23-1013

Hours: 9 a.m. - 5 p.m., Monday - Saturday; closed Sunday

Access: 15-minute walk from Shibata Station, 40 minutes from Niigata on the JR Hakushin Line |

|

|

|

|

Alice Gordenker

Alice Gordenker is a writer and translator based in Tokyo, where she has lived for more than 16 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene she pens the "So, What the Heck Is That?" column for The Japan Times, which provides in-depth reports on everything from industrial safety to traditional talismans. She also translates about early Japanese photography. |

|

|

|