|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Just Your Imagination: Contemporary Works at the National Museum of Art, Osaka

Christopher Stephens |

|

|

| Tadanori Yokoo, A Requiem of Memory (1994). Courtesy of the artist. |

At first glance, the title of this exhibition, Nostalgia and Fantasy: Imagination and Its Origins in Contemporary Art (running through mid-September at the National Museum of Art, Osaka), seems so all-inclusive as to be nearly meaningless. In one way or another, aren't nostalgia and fantasy part of most works of art? Doesn't imagination lie at the heart of every creative expression? Is it even possible to trace the origins of something so fundamental? Some clarification can be found in museum curator Masahiro Yasugi's essay in the show catalogue: "Some people [will] probably [be] disappointed with the use of this overly ordinary combination of words. . . . This is a reasonable response. My intention . . . was to detach the works from contemporary art by using a common expression made up of words that are borrowed from a foreign language but at the same time part of Japanese. . . . One reason [is that] . . . art is no longer an exclusive realm in society."

|

|

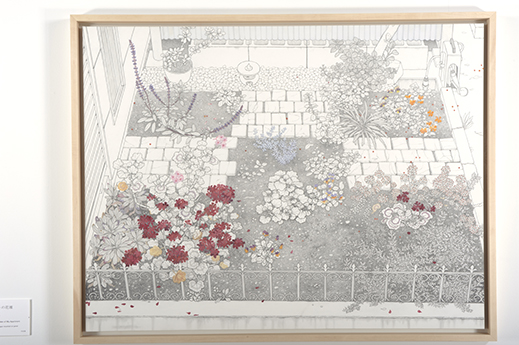

| Yukiko Suto, Flower Beds in the Garden of My Apartment (2014). Artist's collection, courtesy of Take Ninagawa (photo by Shigehumi Kato). |

|

|

|

|

|

Sai Hashizume, Chloris (2011). Private collection, courtesy of Imura Art Gallery (photo by Ken Kato).

|

Yasugi argues that the return to traditional forms such as Nihonga (Japanese-style painting) and line drawing, and the renewed interest in Edo-period and other classical works in recent years, are related to an overriding sense of nostalgia in Japanese society. He also suggests that with the rise of various technologies, the distinction between reality and fantasy has waned to such an extent that the real now dwells within the fantastic. To illustrate this, he has selected nine individuals (two women, seven men) and one group of artists -- ranging in age from their mid-thirties to late seventies -- who are active in a wide range of genres, including painting, drawing, printmaking, installation, and sculpture. He favors people who quietly go about the business of making art without resorting to bold statements and those who reflect the era without intentionally embracing current trends.

By far the most famous, and also the most venerable, is Tadanori Yokoo. Few artists have so consistently relied on memory for material and recorded the inner workings of their conscious and subconscious mind. In A Requiem of Memory (1994), for example, Yokoo quotes a family photograph showing a cluster of smiling relatives in the left foreground. A torii gate juts off at an angle behind them above a slightly eerie crimson river and beneath a sky streaked with oranges and reds and dotted with fluffy black clouds. Cherry blossoms poke out from craggy rocks on either side, and small black-and-white headshots, mostly of expressionless teenagers in school uniforms, are scattered across the painting. At first it seems as if these are younger versions of the relatives, but the old pictures far outnumber the people, so they must actually represent the departed. Whatever the case, the joyous air of the family gathering is complicated by these ghosts from the past, and the scene is imbued with an emotional complexity that the protagonists themselves seem blissfully unaware of.

|

|

|

|

|

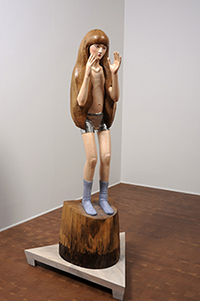

Koji Tanada, Bracing Girl (2014). Artist's collection, courtesy of Mizuma Art Gallery (photo by Shigehumi Kato).

|

Yukiko Suto's drawings of plants and flowers, many in pots or planters or small gardens around typical suburban houses, are probably the most unassuming works in the exhibition. Suto's unpopulated scenes strike us as totally commonplace, and, except for an occasional sprinkling of watercolor, are made up entirely of pencil lines. Rendered in exacting detail, they almost seem to have been traced from a photograph until we realize that standard artistic touches like shading and perspective have been omitted to create a flat (but for some reason more realistic) view of the world. Strangely, this lack of visual depth enhances the works' emotional resonance, giving them a wistful quality, and gradually the utter ordinariness of the scenes makes it seem as if something more must be lurking in the background.

Though Sai Hashizume's paintings bear almost no resemblance to Suto's works, they share a photographic exactitude, all the more so in Hashizume's case due to the whitish glow of artificial light that pours from her pictures and the palpably sensual depiction of the female body. Chloris (2012), used in posters and fliers for the exhibition, shows the bottom half of a woman's face twisted upward toward the right with a pink flower sprouting from her open mouth. Her shoulders are bare, and as in many of Hashizume's works there is a distinctly erotic air. The title is derived from the name of the Greek goddess of vegetation, and the image seems to be a direct reference to this line by Ovid: "As she talks, her lips breathe spring roses: I was Chloris, who am now called Flora."

Koji Tanada's sculptures are among the most striking works in the show. Carved out of a single piece of timber and connected to a base that was part of the same tree, Tanada's painted human figures are all young and terribly undernourished, their rib cages poking through a thin veneer of skin. When they have arms, they are long and spindly; when they are clothed, the clothes are another part of their bodies; and when they have their hair, it fits tightly to their heads like a cap or hood. Their invariably vacant looks are belied by alert eyes angled upward or off to the side, conveying a mood of youthful anxiety and doubt.

Hideaki Shibata and Kazuya Matsunaga, collectively known as Yodogawa Technique, troll the Yodo (a major river running from Lake Biwa to Osaka Bay) for garbage, which they use to make art. The group's principal exhibit here, Let's Become Garbage!, a huge wall of discarded and broken objects like helmets, buckets, shoes, soap containers, and hand fans, was assembled with the help of dozens of volunteers. It is not a pretty sight, especially when we realize that nearly every inch of it is plastic and a regular part of our daily lives. As the title suggests, the work also allows us to reunite with all of these things we thought we had gotten rid of by inserting our faces in one of several holes in the wall and having our picture taken. Positioned at the end of the exhibition, it leaves us with the disturbing thought that old yellow Crocs and blue trashcan lids have replaced daffodils and nightingales as objects of nostalgia and fantasy in the contemporary age.

|

|

| Yodogawa Technique, Let's Become Garbage! (2014). Artists' collection, courtesy of Yodogawa Technique and Yukari Art (photo by Shigehumi Kato). |

|

|

Christopher Stephens

Christopher Stephens has lived in the Kansai region for over 25 years. In addition to appearing in numerous catalogues for museums and art events throughout Japan, his translations on art and architecture have accompanied exhibitions in Spain, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, South Korea, and the U.S. His recent published work includes From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and Gutai: Splendid Playground (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2013). |

|

|

|