|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Architecture in Animation: Studio Ghibli's Design Ethos at the Edo-Tokyo Open-air Architectural Museum

Susan Rogers Chikuba |

|

|

| Architect Terunobu Fujimori and Studio Ghibli film director Hayao Miyazaki share a relaxed moment at the latter's atelier in Koganei, not far from the museum currently featuring their collaborative exhibition. © Studio Ghibli |

Terunobu Fujimori, an architect whose tree houses, airborne tea huts, and, more recently, Storkhouse micro-hotel in Austria dovetail evocatively with the whimsical structures depicted in Ghibli films, has provided editorial direction for Studio Ghibli: Architecture in Animation, now showing at the Edo-Tokyo Open-air Architectural Museum in Tokyo's Koganei Park.

|

| The museum's 17-acre campus of historical buildings is a main attraction of Koganei Park. Takei Sanshodo, at center left and on the right, is a calligraphy shop turned stationer that once stood in Kanda Sudacho. Left: © Akai Photo Life; Right: © Susan Rogers Chikuba |

A short bicycle ride from the Studio Ghibli head office, the museum's 30 carefully preserved structures from the Edo era all the way up to early Showa have long served Ghibli animators in their studies of period-specific design and detail. The townscape on the east side of the museum's campus was Hayao Miyazaki's inspiration for the lost world beyond a tunnel in the 2001 megahit Spirited Away. And the interior of a 1927 stationery store on exhibit here, with an entire wall made of tiny wooden drawers, became the setting where the six-armed Kamaji stores and mixes herbal remedies for visitors to the film's bathhouse -- some architectural elements of which were influenced, in turn, by a traditional sento that stands a bit farther down the lane.

|

|

|

|

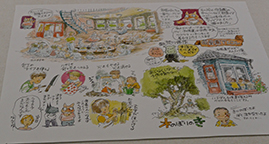

| The hybrid home of the Kusakabe family in My Neighbor Totoro (1988), and the public housing "dining kitchen" of the Tsukishimas in Whisper of the Heart (1995). Their designs, each set in the late 1950s, speak of the different ways in which Japanese and Western residential concepts have melded over time. Left: © 1988 Nibariki - G; Right: © 1995 Aoi Hiiragi / Shueisha - Nibariki - GNH |

Housed in the museum's Visitor Center, the exhibition displays conceptual sketches, establishment shots, background images, and floor plans for buildings and spaces that have starred in 19 feature-length Ghibli films, from the most recent When Marnie Was There (2014) to the debut Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984). Textual commentary by Fujimori, a former University of Tokyo professor, runs among the exhibits, addressing themes as diverse as architectural history in Europe and Japan, kitchen design and changing gender roles, the history of tatami-mat flooring, shear wall vs. post-and-beam structural design, and what it means to build with mud.

|

| Installation view of Architecture in Animation. © Studio Ghibli |

Fujimori's meditations are conversational but heady, and they and all the captions are provided in Japanese only. Still, museumgoers can enjoy the exhibits for their artistic merit alone. Ghibli is renowned for the painterly look of its hand-drawn animations, a style that's clearly evident in the 380 renderings of interiors, exteriors, day and night views, wide shots, and close-ups on show. Even the youngest of visitors will enjoy the models, miniatures, and dioramas that bring familiar anime scenes to life. The exhibition has drawn an unprecedented number of people (100,000 in its first 55 days) to the museum, and when I visited there were as many art students in the galleries as there were children, young couples, and elderly fans. No doubt some of that pull was owed to early August announcements that the studio will be taking a hiatus from production for a while.

|

|

|

|

| Among the exhibits is a sprawling diorama of the mountaintop home featured in Heidi: A Girl of the Alps. A 1974 television adaptation directed by Ghibli cofounder Isao Takahata, it predates the studio by a decade but is one of the earliest collaborations between him and Miyazaki, who worked on the layout and scene design. At right, this ceiling-high, walk-around model of the Spirited Away bathhouse took six months to build. © Studio Ghibli |

The route moves through clusters of films staged in Japan, then Europe, then Japan again. Throughout, one gets a sense of how much detailed and even poetic observation is invested in each and every frame. Marnie director Hiromasa Yonebayashi's conceptual sketches, for example, call for the blush of tomatoes on the vine and the "happy intimacy" of a mailbox, while sweeping scenery shots show the tiniest wire baskets and plant pots overturned pell-mell in the Oiwa family's yard.

|

| The slate mansard roof and clapboard siding of the House of Georg de Lalande, a 1910 structure originally built in Shinanomachi, and various Japanese buildings on the museum's campus. After viewing the Ghibli exhibits, it's fun to walk around the grounds and think about how these and other structures have been referenced by the studio's animators. © Susan Rogers Chikuba |

The last exhibits showcase the fantasy settings of Castle in the Sky (1986) and Nausicaä. Enlarged cross-sections of Laputa, the flying island, are tagged with cuts from actual scenes for a detailed look at how the drama and setting interrelate, and commentary by Fujimori draws parallels between its castle and The Tower of Babel by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. For Nausicaä, which of all the Ghibli feature-length films is the only one set in the future, we learn that the dwelling spaces of the capital Pejite are made of sunbaked bricks after the adobe architecture of Djenné in Mali, and that the people of the valley live in soft-rock cave houses like those of Cappadocia in Turkey. This is pure Ghibli: for all of the industrial machinery, gadgetry, and flying machines that populate so many of the studio's films set in days gone by, the future is evinced by a more primitive or earthy connection between us and our built environment -- a return to basics in the aftermath of having taken on technologies that are too big for us.

|

|

|

|

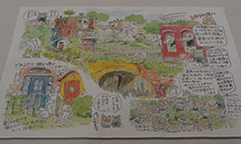

| Illustrated panels by Hayao Miyazaki form an afterword to the show. © Studio Ghibli |

The exhibition concludes with 13 manga panels by Miyazaki that first appeared in Mushime to Anime, a 2008 compilation of his conversations with philosopher Takeshi Yoro. Miyazaki's proposals for the ideal community of the future envision a low-rise, organic world of curving shapes and forms where there are no concrete walls, but plenty of trees with branches just right for climbing. Housing is modeled after the Reversible Destiny Lofts of Shusaku Arakawa and Madeline Gins, cars are parked away from the town center, power lines are underground, and no plastic is in sight. Electric vehicles are available for rent, vending machines are replaced by kiosks and cafés, preschool and eldercare facilities are adjacent to one another, and children, who mostly play outside, already know at kindergarten age how to sew, use knives, tie knots, and build fires. Parents are encouraged to limit viewings of Totoro and other videos to once a year. And because "almighty gods with names" are tricky, shrines are dedicated to ubusunagami -- the guardian deities of one's birthplace. Miyazaki names this blueprint utopia Ihatov, after the dreamland imagined by Kenji Miyazawa, but emphasizes that the choice for such technology-aided sustainable living is ours to make, and needn't be a dream -- since we already once knew how to live this way.

Tokyo may not be your heart's homeland, but the months from now until mid-December, when this exhibition closes, are one of the city's best seasons. Exploring the museum's real-life structures from times past along with imaginative places that live on in anime, while musing over the ways in which these worlds intersect, makes for a sweet autumn outing.

|

|

A former ceremonial hall built on the Imperial Palace grounds in 1940 and moved to Koganei the following year, the Visitor Center is both gateway to the Edo-Tokyo Open-air Architectural Museum and home to its special exhibitions. © Susan Rogers Chikuba

All photographs are by permission of Studio Ghibli and the Edo-Tokyo Open-air Architectural Museum. |

|

|

Susan Rogers Chikuba

Susan Rogers Chikuba, a Tokyo-based writer, editor and translator, has been following popular culture, architecture and design in Japan for 25 years. She covers the country's travel, real estate, hospitality and culinary scenes for domestic and international publications. |

|

|

|