|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Changing Dimensions: The Jiro Takamatsu Exhibition

Christopher Stephens |

|

|

| Strings in Bottles (1963; reproduction made in 1985), The Estate of Jiro Takamatsu |

At first glance, there doesn't seem to be anything particularly remarkable about the shadow on the wall. It has a human form and apparently belongs to someone standing nearby. But then you see that there are actually two shadows with identical forms, slightly staggered and not quite the same size, which overlap in the middle. This must mean that there are two light sources positioned at different angles overhead. Then you suddenly realize that there isn't anyone else around, and since you're the only one standing there, shouldn't the shadow be yours?

This is one of many curious and unnerving discoveries that await at the Jiro Takamatsu: Mysteries exhibition, running through March 1 at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. Born in Tokyo in 1936, Jiro Takamatsu was an extremely prolific artist with a wholly unique and intricate worldview, developed over a 40-year career that ended with his untimely death in 1998.

|

No. 273 (Shadow) (1969), The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo |

Takamatsu first rose to prominence in the early 1960s after forming the now legendary Neo-Dada group Hi-Red Center with Genpei Akasegawa and Natsuyuki Nakanishi (the group's name was derived from the literal translation of the first Japanese character in each artist's surname; "taka," for example, means "high"). Staging unannounced happenings in public places, the group performed seemingly nonsensical actions such as dragging long pieces of spiky black string across a train platform, and scrubbing down a Ginza sidewalk while clad in white lab coats to "promote cleanliness and order in the metropolitan area." The latter was intended as a satirical jab at the city's overzealous efforts to prepare for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

String also figured in Takamatsu's solo pieces of the period. In one work, he wove a thick web, using string of various colors and thicknesses, around household items like lamps and desks, and in another, he heaped hundreds of pieces of white rope on top of a ladder until it was nearly hidden from view. And though Takamatsu's work was never overtly political, Strings with Bottles, consisting of a group of empty cola and beer bottles, each packed tightly with a long piece of string with one end trailing outside, would certainly have reminded contemporary viewers of Molotov cocktails and the student protests that were raging at the time.

|

|

|

|

|

|

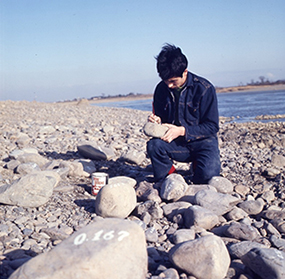

Stone and Numeral (1969), Fuchu Art Museum |

|

Compound (Chair and Brick) (1972), The Estate of Jiro Takamatsu |

Takamatsu developed approximately 20 series over the years. The longest running ones, String and Shadow, spanned almost his entire career. Others, like the Stone and Numeral series, ran their course after only a year or two. In the latter work, Takamatsu picked up stones from the dry bed of the Tama River and painted numbers on them. He began with the decimal 0.1 and after exhausting all of the two-digit numbers, moved on to three digits until he reached 282 (or perhaps 279 -- accounts differ). Inspired by the "potential of infinite proliferation," Takamatsu used this and similar methods to pursue his eternal goal of attaining the "true totality" of a given object.

On the other hand, the Compound series, begun in 1972, focused on two or more objects. Takamatsu took ordinary things like chairs and bricks and combined them in ways that rendered them useless. This approach also negated the words "chair" and "brick." Reduced to simple vertical, horizontal, and diagonal elements, the objects could then be used to represent physical laws.

|

|

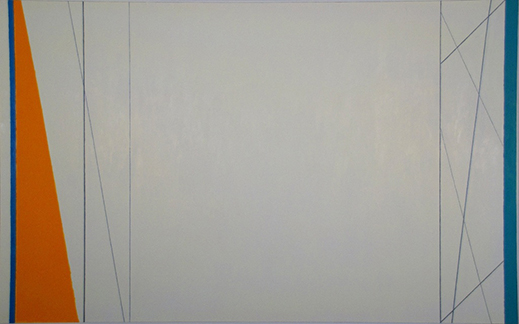

Space in Two Dimensions No. 1035 (1982), Church of Perfect Liberty

All works by Jiro Takamatsu. All images © The Estate of Jiro Takamatsu, provided courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates. |

Takamatsu later expanded on this idea by trying to eliminate one dimension of a solid to make a plane. Then he reintroduced the lost dimension to show that objects do not necessarily retain their original form and are likely to become distorted in the transition from, say, two to three dimensions. One concrete example is the Space in Two Dimensions series, which often recalls a geometric pattern or schematic drawing, but as the title suggests, is not intended to depict a space but rather to be one. Thus the works are not, in the strictest sense of the word, paintings.

Some visitors to the exhibition may be put off by the abundance of text (in both Japanese and English). Nearly every work is accompanied by a lengthy description, including quotations from the artist and background information. Bypassing these is of course an option, but truly understanding Takamatsu's work requires more time and effort than the average artist, as his ideas are complicated and frequently allude to an obscure scientific or philosophical notion. (The exhibition does start off light, however, with an interactive area called "Shadow Lab," which helps unlock the mysteries of the Shadow series.) The complexity of Jiro Takamatsu's vision has unfortunately led to misunderstandings about the true nature of his art, but this exhibition, and a second, completely different and larger one slated for April at the National Museum of Art, Osaka, should help set the record straight.

|

|

Christopher Stephens

Christopher Stephens has lived in the Kansai region for over 25 years. In addition to appearing in numerous catalogues for museums and art events throughout Japan, his translations on art and architecture have accompanied exhibitions in Spain, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, South Korea, and the U.S. His recent published work includes From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and Gutai: Splendid Playground (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2013). |

|

|

|