|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Gentle Acts of Subversion: The Genpei Akasegawa Exhibition

Christopher Stephens |

|

|

|

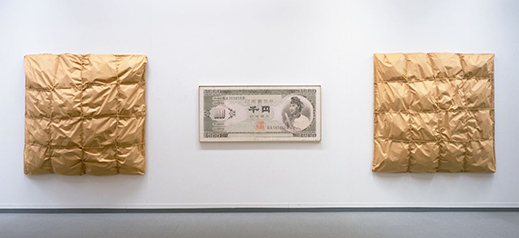

Fact or Method 1, 2 (1963/1994), left and right side; Morphology of Revenge (Take a Close Look at the Opponent before You Kill Him) (1963), center |

There has probably never been a better ambassador for Japanese contemporary art than Genpei Akasegawa. Universally admired and profusely talented, Akasegawa made his name in fine art, but went on to draw manga, take photographs, and write countless books on an array of subjects. His fine art was obscure enough to earn the praise of hardcore enthusiasts, and his writing accessible enough to attract a wide readership. Akasegawa is best remembered by the general public for his 1998 book Rojin Ryoku (Senior Power), in which he argued that symptoms of decline such as memory loss were actually proof of increasing strength in later life. Like everything he did, the book is notable for the artist's unique sense of humor and style.

Featuring over 500 items from throughout Akasegawa's 50-year career, "The Principles of Art" by Akasegawa Genpei: From the 1960s to the Present (running through the end of May at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art) is likely to stand as the most comprehensive introduction to the artist's work for many years to come. Unfortunately, Akasegawa, who suffered from a string of ailments over the years and had undergone surgery for stomach cancer in 2011, succumbed to sepsis two days before the traveling exhibition first opened at the Chiba City Museum of Art last October.

|

|

Canned Universe (1964/1994) |

Born in Yokohama in 1937, Akasegawa spent most of his childhood in Oita Prefecture, where he met the future architect Arata Isozaki and the artist Masanobu Yoshimura, before eventually graduating from high school in Aichi Prefecture, where the artist Shusaku Arakawa was one of his classmates. After moving to Tokyo in the mid-'50s and attending Musashino Art University, Akasegawa followed what was then the accepted path for a budding artist by showing his work in invitational exhibitions like the Yomiuri Independant. In 1959 he became involved with the Neo Dadaism Organizers, a short-lived but now legendary group that included Yoshimura, Arakawa, and Ushio Shinohara among many others.

In 1963 Akasegawa formed Hi-Red Center, an experimental performance group, with Natsuyuki Nakanishi and Jiro Takamatsu (the group's name was derived from the literal translation of the first Japanese character in each artist's surname; "aka," for example, means "red"). Operating anonymously, Hi-Red Center made use of "direct actions" and printed matter that appeared to be part of everyday life but were actually intended to undermine it. These projects included the "Shelter Plan" (1964), in which the artists rented a room at the Imperial Hotel and invited certain friends and associates to be measured for custom-made, single-occupancy nuclear shelters. Participants such as Yoko Ono and Nam Jun Paik were photographed from all four sides and the top of their heads and bottom of their feet to produce a folded rectangular model, and medical charts with detailed physical data such as the size of each person's mouth cavity were filled out and authorized with the subject's fingerprint. Over 50 plans were completed, but the shelters were never actually built.

|

|

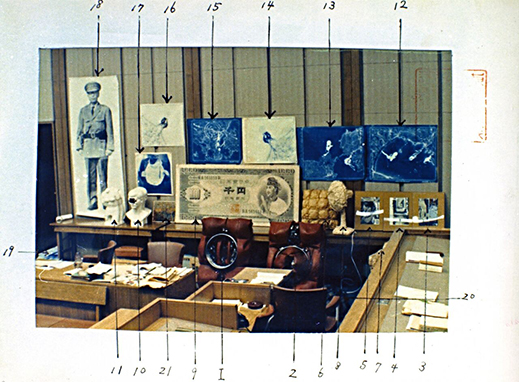

1,000-Yen Note Incident Round-Table Conference, The Great Courtroom Exposition (1966/1994),

© 1,000-Yen Note Incident Round-Table Conference |

In 1964 Akasegawa also received a visit from the Tokyo Metropolitan Police in connection with several replicas of a 1,000-yen bill (which at the time bore a picture of the sixth-century regent Shotoku Taishi) he had made the previous year. The authorities had come across the copies at a small printing company while in the process of investigating an allegedly obscene book that a low-ranking member of a crime syndicate had been carrying when he was arrested for shoplifting. This led them to suspect that Akasegawa was in some way connected to a high-profile counterfeiting case called the Chi-37 Incident, an allegation that the Asahi Shimbun newspaper repeated. Termed an "ideological pervert" by the police commissioner, Akasegawa and the two printers were charged with "making something that could be mistaken for money," rather than intentionally setting out to produce fake bills (the reverse side of the main work, Model of 1,000 Yen Note, was blank; the others carried information about an exhibition).

The case has endured as one of the strangest incidents in Japanese art history, and continues to be studied not only because of the absurd charges, but because the court proceedings attracted a who's-who of contemporary cultural figures, including the critic Shuzo Takiguchi and the writer Tatsuhiko Shibusawa, who took the stand in Akasegawa's defense. Photographs also reveal that the courtroom was literally transformed into an exhibition, with examples of Akasegawa's pictures tacked up on the walls, sculptures displayed on cabinets and chairs, and Nakanishi's work All Men's Catalogue '63, a long scroll of life-sized nude photographs of the Hi-Red Center members shot from behind, stretched across the public gallery. The trial itself began in 1966 and ended with Akasegawa being found guilty and receiving a suspended sentence of three months. He appealed the decision twice in an effort to have the printing plates and other confiscated materials returned to him, but finally lost in 1970.

|

|

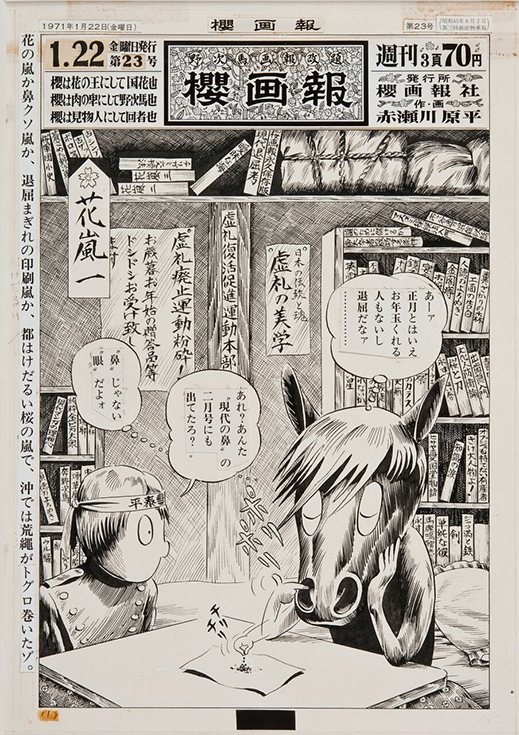

Sakura Gaho No. 23: Flower Storm 1-1 (1971) |

In the '70s Akasegawa turned to more introspective pursuits, publishing highly realistic and detailed satirical cartoons in various publications including his own newspaper Sakura Gaho (Cherry Blossom Pictorial) and the underground manga magazine Garo. He also collected colorful matchboxes and magazine advertisements, and combined them to create and reveal new meanings. This was followed by two slightly more scientific but equally humorous approaches to art that hinged on the discovery of curious sights in everyday places. The first focused on photographing practical objects that seemed to have no actual use, such as doors that opened onto walls and staircases that led into space. Akasegawa named these "Thomassons" after a foreign baseball player who had been recruited by the Yomiuri Giants with much fanfare only to strike out repeatedly.

The second, a similar but more open-ended methodology, led Akasegawa to form the Street Observation Society, a group that documented and analyzed roadside oddities like "plant wipers" (swaying vegetation that had apparently left semi-circular marks on concrete walls) and handwritten signs made by local residents to offer helpful advice on mundane activities like putting out the garbage that could be interpreted in an inadvertently funny manner.

Though the medium for Akasegawa's expressions varied, he remained constantly active and inventive throughout the last half century. This is abundantly clear from the huge number of displays and explanations (in Japanese with some English) in the exhibition, which makes for a fascinating afternoon at the museum and confirms that Akasegawa is one of Japan's true cultural treasures.

|

|

Pure Staircase at Yotsuya Shoheikan (1972)

All works by Genpei Akasegawa. All images © The Estate of Genpei Akasegawa, except where otherwise noted; provided courtesy of the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art.

|

|

|

Christopher Stephens

Christopher Stephens has lived in the Kansai region for over 25 years. In addition to appearing in numerous catalogues for museums and art events throughout Japan, his translations on art and architecture have accompanied exhibitions in Spain, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, South Korea, and the U.S. His recent published work includes From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and Gutai: Splendid Playground (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2013). |

|

|

|