|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

No Fire This Time: Kawagoe's Kurazukuri Museum

Michael Pronko |

|

The facade of the Kurazukuri Museum reveals the thickness of the storehouse walls through the window openings upstairs. Other structures had thinner wood walls, and were allowed to burn if a fire broke out. |

The city of Kawagoe, an hour outside of Tokyo, boasts one of Japan's first fireproof business districts. After numerous conflagrations burned down its bustling merchant storehouse zone, Kawagoe built itself back up to withstand disaster. It is well worth the train ride to Kawagoe and its fascinating Kurazukuri Museum to find out just how they did that, and did it so beautifully.

Housed in a shop, residence and storehouse complex built after one of the most devastating fires in 1892 by a tobacco merchant (this was in the days before tobacco became a state monopoly), the museum lets visitors wander inside what was once a home and business. The buildings themselves are the main exhibits, but they also contain absorbing smaller displays with maps of the fires, merchant association posters, and explanations of construction and firefighting techniques. One sees how the merchants lived, but also how they survived. After all, kura, meaning storehouse or warehouse, are one of the oldest types of structures in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

A piece of the roof set on the ground for closer inspection. The design for this tobacco merchant's storehouse is a bit plainer than that of many other roofs in the district, some of which are extremely elaborate. |

|

Buildings for living quarters and shops were made from wood, while the expensive fireproofed construction was saved for the storage of valuable property and goods. |

During the Edo period (1603-1867), Kawagoe had a thriving trade distributing goods to the ever-expanding government seat of Edo (now Tokyo), just a few miles downriver. Everything from candy and sake to lumber and tobacco was produced, stored and sent on boats down the nearby Iruma River, which flowed conveniently into the Arakawa and Sumida Rivers, and on through the heart of Edo.

Because of its close connection to Edo, Kawagoe is nicknamed Ko-Edo, or "Little Edo." That name fits especially well since the numerous earthen, black-roof-tiled warehouses along its main street were copied from those of Nihonbashi merchants. Even today, looking down the thoroughfare (and ignoring the traffic), one can still conjure a vision of how things must have looked over a hundred years ago.

The museum is one of the plainer buildings in the district, however. Many of the others that line the street have more elaborate designs on their walls, tiles, windows and doors. But in the museum, the attention to aesthetic detail can be seen up close. The merchants spent lavishly on their homes and storehouses, not just to build fire-resistant structures -- with special walls made from layers of clay -- but also to make them look nice. Their fire-preventing function and attractive form are in perfect harmony.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Some of the firefighting equipment on display, with water pumps in the foreground. In the case in back are samples of the tough, thick clothing worn by firefighters, including a coat bearing a protective dragon design. |

|

A cutaway section of wall, exposing the bamboo lattice, wood struts, and layers of different types of clay and plaster, shows just how much time, effort and money went into building the storehouses. |

The museum displays design plans, cross sections of the walls, roof tiles, fire-resistant doors, and even the firefighting equipment every merchant kept on hand -- though most firefighting in those days consisted of tearing down buildings to make firebreaks. Waterworks were yet to be developed.

Some of the storage structures were designed for items that could be easily carried to safety in case of fire, but others were made for harder-to-carry goods. Those buildings could be sealed tightly shut to keep the fire outside and the valuables safe inside. Especially interesting is the anagura, an underground vault set into the floor at the building entrance that is large enough for a person or two and plenty of small valuables. The merchants seemed to put a value on everything and to have a plan for every contingency.

That planning was important since in those days, the warehouses held the merchants' entire financial assets. The numerous fires of the period played havoc not just with the lives of the merchants themselves, but also with the entire local economy. A fire could wipe out the whole material and monetary network of the city, causing runaway inflation, upending distribution, and destabilizing markets. In that sense, the merchants' well-protected warehouses became one of the building blocks of Japan's modern economy.

|

|

|

|

|

|

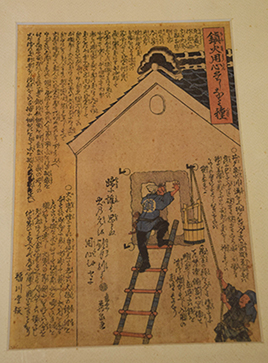

An ukiyo-e woodblock print explains how the windows could be plastered shut in case of fire. |

|

Squat, stodgy, yet rich in small details, the storehouses performed their essential function of storing goods safely while also maintaining an aesthetic appeal with bold lines, balanced sections, and special touches meant to display status.

All photos by Michael Pronko. |

The Kurazukuri Museum, and the old storehouse zone around it, is the best place to start looking around town, but Kawagoe is also home to the Kawagoe City Museum, the Kawagoe Art Museum, Kawagoe Castle's Honmaru Goten buildings, and the lovely Kita-in temple, with its statues of 500 rakan disciples of the Buddha, as well as Kashiya Yokocho ("Candy Alley"), which stretches out behind the museum. Around the corner from the museum is a bell tower built to watch for fires as well as to tell time, two basic necessities for merchants.

Both the Kurazukuri Museum and Kawagoe itself offer a fascinating view of how closely connected economics and history are to architecture and building. Though one needs some imagination to piece together how it would have all looked in the Edo period, the museum helps to paint a vivid picture of this complex, interlocking network of production, warehousing, distribution and living, all set in appealing, intriguing buildings.

|

| | Kawagoe City Kurazukuri Museum (in Japanese only) |

| | 7-9 Saiwai-cho, Kawagoe, Saitama

Phone: 049-222-5399

Hours: 9 to 5 (last entry 4:30); closed Mondays

Access: Kawagoe has two main stations, Kawagoe (on the JR Kawagoe and Tobu Tojo Lines) and Hon-Kawagoe (on the Seibu Shinjuku Line), both roughly one hour from downtown Tokyo. |

|

|

|

Michael Pronko

Michael Pronko teaches American literature, film, art and music at Meiji Gakuin University. He has appeared on NHK, Sekai Ichiban Uketai Jugyo, and other TV programs. His publications include several textbooks and three collections of essays about Tokyo. He writes regular columns for Newsweek Japan, ST Shukan, The Japan Times, and for his own websites, Jazz in Japan and Essays on English in Japan. |

|

|

|