|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

A Forest Grows in Otemachi

Susan Rogers Chikuba |

|

A worker tends grounds that are knee-deep in ferns. Is this really central Tokyo? |

When the real-estate firm Tokyo Tatemono Co., Ltd. and architecture giant Taisei Corporation first announced detailed development plans for Otemachi Tower in the heart of Tokyo's financial district, their greening proposal seemed almost utopian: a biodiverse forest of some 200 deciduous and evergreen trees and a ground cover of ferns, grasses, and wildflowers? All of this watered by manmade conduits fed by rainwater and engineered to mimic the underground streams of a naturally undulating landscape?

|

|

|

|

|

The paved walkway through Otemachi Forest shows the typical tree-planting pattern of most urban plazas, with little space left around the trunks for ground seepage. But here, the adjacent woodland carpet absorbs plenty of rain, and the passageway is gently pitched toward it so runoff heads in the right direction.

|

It seemed an amazing scheme for the design of an urban public space, and well beyond oft-heard corporate claims about mitigating the heat-island effect. If pulled off, the 3,600-square-meter Otemachi Forest, occupying one third of the property's total site area, would be a real departure from the typical setback plaza that's dotted with a few carefully pruned trees, each one sprouting forlornly from a square patch of dirt in a hard expanse of concrete or tiled stone.

As it turned out, the developers' vision for Otemachi Forest, realized in 2014, was no hollow sound bite. Granted, its creation was motivated in part by a municipal provision that relaxes the maximum allowable floor area for large-scale developments that are deemed to enhance their host district in some distinct way. (Otemachi Tower garnered a FAR index of 16, the highest at that time in Tokyo. That means its total floor area could be 16 times the size of the site.) But beyond assertions that the woodland floor will improve the drainage of this low-lying section of the city and that the plantings will help lower temperatures and improve air quality in the neighborhood, the story of how this unlikely oasis came to be is essentially a humanistic one, more along the lines of "Because it'd be nice to have a forest here, wouldn't it?"

|

|

|

|

|

|

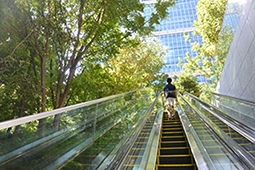

Natural light from the forest and its sunken plaza fills the terraced void of the first floor and two basement levels of Otemachi Tower. A ride on the escalator from the lower-level shops and subway lines delivers city dwellers into a refreshing world of green. |

The creation of Otemachi Forest began as early as 2004, when the property was slated for redevelopment. Over time the project evolved into a full-scale study of how natural woodlands grow and mature, and how such an ecosystem could be successfully planted to thrive in the city center given this site's particular conditions for soil, wind, and light. With few, if any, pertinent case studies to sample, the developers did the unprecedented: years before Otemachi Tower was to be completed, they established a test nursery at a rural arboretum 70 kilometers away across Tokyo Bay in Kimitsu, Chiba Prefecture. There they poured concrete at varied heights and pitches to simulate the planned lay of the land at the Tokyo site, filled that foundation with soil, and, in consultation with a team of arborists, selected trees of varying ages, all native to the Kanto region. These were then planted to grow at their ideal soil depth and canopy width. One third the scale of the eventual forest, this "pre-forest," as it was called, was later transferred to Tokyo and then tripled in size.

|

|

|

|

|

|

A stream runs through Otemachi Forest, nurturing its varied flora. It's fed by rainwater that's captured on site and recycled; at right is one of several collection points. |

Indigenous ground-cover plants were incubated at Kimitsu, too. For three years this entire plot of land, including the drainage system engineered for replication in Tokyo, was carefully tended and fine-tuned while the Otemachi property was first razed and then rebuilt. With the trees healthily growing and their root system firmly established, the Kimitsu plot was transferred, foundation and all, to its destined home in the capital in 2013, once the tower construction was largely done.

The tree mix -- 18 species altogether -- includes several kinds of pine, oak, and beech, randomly clustered for variations in height and trunk girth as well as for gaps where plants can flourish. It's a relatively young ecosystem as woodlands go, because the plan is to let Otemachi Forest evolve naturally for at least another century or two. What little signage there is on the site is rendered in translucent glass so as not to block sight lines. Glass screens, thoughtfully designed for both plants and people, border the forest on three sides, cutting out artificial wind gusts from surrounding towers as well as exhaust fumes while serving as discreet lighting for pedestrians at night.

|

|

|

|

|

|

No fussy manicuring means the trees appear as they do in nature. Sunlight dapples the lush ground cover. |

In the first year after the move, eight of the 14 anticipated species of songbird had been sighted, at least 66 insect species were in residence, and some 280 species of plants (more than half of them unplanned newcomers) were thriving, among them dogtooth violets, bramble fruit, lilies, and anemones. Rainwater collected from the tower roof and from seepage through the forest floor is stored underground in tanks, to be recycled into the sprinkler system and the stream that runs through the site. Weeding is a relaxed affair, conducted once weekly and targeting only invasive species not native to Kanto. Leaves are mostly left to decompose where they fall, eventually returning to the soil. And the forest's planners hope that its proximity to the Imperial Palace gardens will boost the area's bird population still more: while brown-eared bulbuls, white-eyes, dusky thrushes, Oriental turtle doves, sparrows, green finches, and more have already caught on to the new digs, starlings, buntings, woodpeckers, shrikes, and other likely species are still on the watch list.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Much of the enjoyment of Otemachi Forest comes from observing its seasonal transitions close-up. |

Sitting atop the Chiyoda, Hanzomon, Marunouchi, Mita, and Tozai subway lines of Otemachi Station, Otemachi Forest is a real gift of civil engineering to Tokyo, in particular to a district whose population swells each weekday from a mere two digits to hundreds of thousands of people. Headquarters for the Mizuho Financial Group, the site is just two blocks from the Otemon gate of the Imperial Palace and connects directly to Naka-dori, a pedestrian-friendly commercial lane that leads through Marunouchi all the way to Yurakucho. For visitors exploring on foot as well as office workers on break it's a spot where, to paraphrase the naturalist John Muir, you might receive far more than you seek. Muir also said that a doorway to a new world lies between every two pines, and that's something the inspired team at Tokyo Tatemono and Taisei have demonstrated for sure.

|

|

Texting, talking, reading, eating. The things we spend our time doing may not differ so much from day to day, but the setting can make all the difference.

|

All photographs are by the author.

|

|

| | Otemachi Forest |

| | 1-5-5 Otemachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo

Open daily year-round |

|

|

|

Susan Rogers Chikuba

Susan Rogers Chikuba, a Tokyo-based writer, editor and translator, has been following popular culture, architecture and design in Japan for three decades. She covers the countryfs travel, art, literary and culinary scenes for domestic and international publications. |

|

|

|