|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Rediscovering a Modern Master of Japanese Architecture: Takamasa Yosizaka

James Lambiasi |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Takamasa Yosizaka. (Photo: Atelier U) |

The postwar construction boom in Japan was a time of prolific achievements among Japanese architects, many of whom were considered "modern masters" for their pioneering designs. A select number of these architects became well known internationally, and interest in the history of their works needs no extra promotion. Other architects, on the other hand, have a bit more obscure place within Japanese architectural history and consequently need a bit more attention in order to discover their significance. Takamasa Yosizaka is an architect of this latter sort; his work today is not very well known, but the breadth of influence he had on modern Japanese architecture is literally built all around us. Discovering the importance of Yosizaka's work is possible through the meticulously curated exhibition at Tokyo's National Archives of Modern Architecture, Discontinuous Unity: Architecture of Yosizaka Takamasa + Atelier U.

There are two important aspects to consider when viewing firsthand this collection of works by Yosizaka. One aspect is his role in providing a major link between Japan's burgeoning architectural development in the 1960s and 1970s and the design philosophy of the master of modern architecture, Le Corbusier. Yosizaka worked in Le Corbusier's atelier in Paris for two years before setting up his own office, Atelier U, in 1964, and he was instrumental in translating many of his mentor's works from French to Japanese. He was also one of three Japanese architect apprentices of Le Corbusier who oversaw the only project by Le Corbusier realized in Japan, The National Museum of Western Art.

|

|

|

|

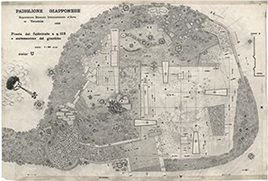

Japan Pavilion, Venice Biennale, first-floor plan drawing depicting the open-air piloti ground level zone, 1984 (redrawn). (Property of National Archives of Modern Architecture) |

|

Model of the Yosizaka House. (Exhibit photo by James Lambiasi) |

The second important aspect to understand is that while Yosizaka utilized the technology and architectural vocabulary of Le Corbusier, he redefined the use of concrete by focusing the purpose of design on community and human relationships. Whereas the sculptural forms of Le Corbusier retained more of an artistic formality, the aesthetic developed by Yosizaka seems to melt forms softly, deferring to the movement of people to explain their shape. This is evident in his design method of sculpting with clay, which exemplified the visceral relationship he saw among people, place, and material. This desire to reflect the simultaneous nature of human relationships, which he saw as establishing unity while not sacrificing the identity of individual parts, led him to develop his influential theory of design collaboration known as "discontinuous unity."

|

|

|

|

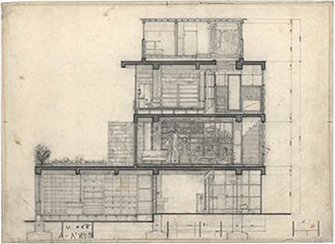

Yosizaka House, measured section drawing, 1973.

(Property of National Archives of Modern Architecture) |

|

Yosizaka House, 1955. (Photo: Eiji Kitada, 1983) |

The exhibition presents Yosizaka's work in four segments representing important aspects of his theory of discontinuous unity through house, form, organization, and civilization. The house represented the first base of community to Yosizaka, being the family. Including his own home, the exhibits of houses illustrate his view of house as layered ground planes on which different activities may occur. Yosizaka saw form as the product of discussion, collaboration, and hands-on work. Be it a roof shape that sheds snow, a building cantilevering off a mega-column structure, or a conical building embedded in the landscape, Yosizaka treated form as an extension of the collaborative process and consequently imbued with life. The exhibits depicting organization embody his aforementioned design methodology of collaboration and group discussion. This is very evident from the central exhibit, an oil-based clay model of the Inter-University Seminar House in Hachioji. Probably the best known of his built projects, this is a village-like camping complex that exudes life through the vitality of its individual forms while simultaneously knitting seamlessly with the undulating landscape of the site. The fourth area of exhibits regarding civilization depicts the way in which Yosizaka's political views were intertwined with his views of community and equality. Global maps with reversed orientations show his concern with political hierarchy on a global scale, while life-sized scale details show his keen interest in the interaction between materials and humans.

|

|

Overview of exhibits. (Photo by James Lambiasi) |

On a personal note, I must admit that my favorite exhibit is indeed the 1:50 scale model of the Inter-University Seminar House. Over the past 20 years I have had the opportunity to conduct workshops with architecture students in this complex, and the feeling of wonder and inspiration one has when navigating a stair through an inverted pyramid or conducting class on an undulating rooftop truly reveals his love for connecting human activities. Interacting with this model, as well as the other exhibits, is a great opportunity to experience firsthand Takamasa Yosizaka's "discontinuous unity," and the contribution he made in creating a humanistic approach to architecture.

Inter-University Seminar House, section drawing of main building, 1963. (Property of National Archives of Modern Architecture) |

The inverted pyramid-shaped main building. (Photographed 1997; property of National Archives of Modern Architecture) |

Clay model exhibit of Inter-University Seminar House.

(Photo by James Lambiasi) |

|

Plan exhibit of Inter-University Seminar House, Matsushita House. (Photo by James Lambiasi) |

Clay model exhibit of Inter-University Seminar House. (Photo by James Lambiasi) |

|

All photos reproduced by permission of the National Archives of Modern Architecture, Agency for Cultural Affairs.

|

|

|

James Lambiasi

Following completion of his Master's Degree in Architecture from Harvard University Graduate School of Design in 1995, James Lambiasi has been a practicing architect and educator in Tokyo for over 20 years. He is the principal of his own firm Lambiasi + Hayashi Architects, has taught as a visiting lecturer at several Tokyo universities, and has lectured extensively on his work. James served as president of the AIA Japan Chapter in 2008 and is currently the director of the AIA Japan lecture series that serves the English-speaking architectural community in Tokyo. He blogs about architecture at tokyo-architect.com. |

|

|

|