|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Sense of Place: The Warm Gaze of Seiichi Motohashi at Izu Photo Museum

Susan Rogers Chikuba |

|

I was too late for the canopy of white and purple wisteria that accents the long leafy approach to Izu Photo Museum each spring, but the adjacent Clematis Garden will be popping with flowers to enjoy all summer, along with the sculptures by Giuliano Vangi. Photos by Susan Rogers Chikuba |

The first thing you'll notice upon arrival at the hilltop art complex Clematis no Oka in Shizuoka Prefecture is the fragrant scent -- right there in the parking lot -- of meadow flowers. A few deep breaths of this potent tonic, and any world-weary city woes give way to mounting anticipation: here on this sprawling site in the foothills of Mount Fuji are four museums, a sculpture garden, and wooded trails to explore. Among these delights is the Izu Photo Museum, which through July 5 is showcasing five decades of photographs and films by Seiichi Motohashi.

|

|

|

|

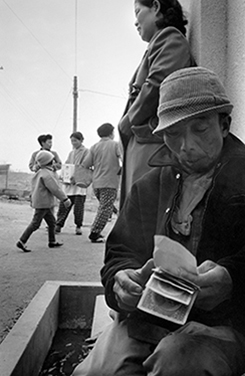

| It seems hard to believe that these photographs of Ueno Station, shot between 1980 and 1982, are not from a far more distant past -- note the stenciled departure times updated by hand, and matter-of-fact campouts on the floor. © Motohashi Seiichi |

A prolific photographer well known for his books, Motohashi has documented life's hard beauty in such disparate settings as coal mines, fishing communities, circuses, and an Osaka slaughterhouse. Many of his publications target the YA set and continue to be staples of school library holdings today, years after their first editions were released. Yama (The Coal Mine) won the Taiyo Prize in 1968; Nadya's Village, one of several works chronicling the aftermath of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, took the 1998 Domon Ken Award. His Abattoir, published in 2011, was the first book ever compiled on a Japanese slaughterhouse, a subject long fraught with taboo issues of worker discrimination. The daunting scale of the Chernobyl accident and the difficulty of documenting it with stills alone prompted Motohashi to revisit an old interest in moving images as well. His film version of Nadya's Village was released in 1997, followed by Alexei and the Spring in 2002. Both depict the lives of villagers who chose to stay on in the exclusion zone, farming and raising animals and continuing to live off the land.

All of these themes and more -- a total of nine bodies of work from 1963 to 2015, encompassing well over 200 prints and excerpts from five films -- are on display. The Chernobyl series is given the most weight, clearly because of the immensity of the disaster, but also because this year marks the thirtieth and fifth anniversaries respectively of the meltdowns in Russia and Fukushima.

|

|

|

|

Five years after the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster, Motohashi was asked by the Japan Chernobyl Foundation to document its aftermath. These scenes are from the Belarusian Research Center for Pediatric Oncology and Hematology (1991), and Ippolitovka Village in Chechersk, Belarus (1994), where seedlings sun in a window, awaiting planting in the soil. © Motohashi Seiichi |

Closer to home, Motohashi's Ueno Station series looks at the days before bullet-train extensions diminished that terminal's role as the gateway to Tokyo for travelers and migrants from the north, namely Tohoku and Hokkaido. Slaughterhouse, also from the 1980s, covers a time not very long ago when meat processing had yet to be mechanized. The municipal facility near Osaka where Motohashi took these shots is no longer in operation. In a day when so few of us slay the animals we eat with our own hands, the series stands, in the artist's words, as a record of "people who connect lives to other lives."

Matsubara, Osaka, 1986 © Motohashi Seiichi |

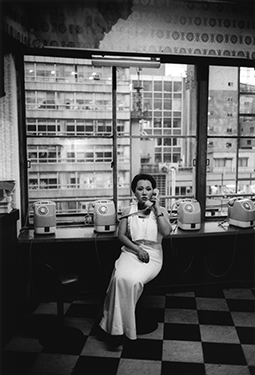

Although Motohashi focuses his lens on the hardscrabble lives of ordinary people left in the lurch of failed or transforming economic and social models, what we see through his warm gaze is not struggle but rather the strength, tenacity, and inherent hope of the human spirit. To its credit the exhibition does not present the nine series chronologically (there are more discoveries to be made when timeframes are mixed up), but for the record they are Ofuyu (1963-), Yoron (1964-), The Coal Mine (1964-), Performance East and West (1972-), Circus (1976-), Ueno Station (1980-), Slaughterhouse (1986-), Chernobyl (1991-), and Arayashiki (2011-).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The Ofuyu and Yoron series sampled above are Motohashi's earliest, and premiere at this show. Straddling Japan north and south, they take us to a remote fishing village in Hokkaido (top) and a small island southeast of Kyushu (bottom) that lost many residents to the 1963 Mitsui Miike coal mine disaster. Ofuyu, Hokkaido, 1963-4 and Yoron, Kagoshima, 1964 © Motohashi Seiichi |

A number of photographers visited Japan's coal mines in the 1960s to document what had been the backbone of the country's rapid economic growth, even as mining had begun to give way to oil imports. Motohashi's own interest in the subject was spurred by nonfiction writer Eishin Ueno's Owareyuku kofutachi (Miners under the Gun) and Ken Domon's photo book Chikuho no kodomotachi (Children of Chikuho), both 1960 bestsellers detailing the poverty and harsh working conditions of Kyushu coal miners.

Seeking a deeper understanding of the miners' lives than presented by Domon's photorealism, and enamored of Ueno's live-in documentary style (the essayist had moved with his family to Chikuho and became a miner himself to better understand the conditions he observed), Motohashi took the Kyushu mines as the subject of his college thesis and continued to photograph the demise of the coal industry and related loss of livelihood for individual families there and in Hokkaido for three more years. He maintains that he learned more from Ueno's approach and intimate line of sight as a writer than he did from any photographic records of the time. That compassionate stance defines his work to this day.

|

|

This photo of a wedding in a contaminated zone of Belarus begins and ends the exhibition, inviting us to rethink our impressions before and after. Dudichi Village, Chechersk, Belarus, 1996 © Motohashi Seiichi |

Motohashi was schooled at Jiyu Gakuen, renowned for a curriculum that fosters independent thinking and social service. In 1956, at the tender age of 16, he saw the groundbreaking MoMA exhibition The Family of Man when it came to Tokyo. While moved by its optimistic humanism, he later realized that he was uncomfortable with the notion of lumping diverse ethnicities, religions, and cultures together in the name of unity. He became aware that his personal credo is closer to the idea that we are, each of us, a universe, and so our ultimate challenge is to accept one another even with our many differences.

|

|

|

|

|

Chikuho Region, Fukuoka, 1965 © Motohashi Seiichi |

Haboro Coal Mine, Haboro, Hokkaido, 1968 © Motohashi Seiichi |

|

|

|

|

|

Gomel, Belarus, 1991 © Motohashi Seiichi |

|

Shirovichi Village, Chechersk, Belarus, 1993 © Motohashi Seiichi |

Throughout his career Motohashi has spent long periods of time with his subjects, crawling with them into mine shafts, purchasing their produce grown on irradiated soil, breaking bread with them, celebrating their triumphs of paydays and weddings. The show's title, Sense of Place, reflects his view that, whether alone as individuals or together as communities, we carry a place within that is unique and that continues to evolve. Real exchange and learning happen when we pause to observe and bear witness to that diversity and flux. "On my first visit to Belarus," he writes, "I was appalled by the idea of photographing children suffering from leukemia and thyroid cancer. At the plant, too, standing in front of that sarcophagus with a Geiger counter wildly beeping, I thought this was a place that I should never return to again." Those feelings changed when Motohashi was taken to Chechersk and introduced to villagers who had determined to stay on in a contaminated zone some 170 kilometers north of the accident. Chernobyl is the work of more than 30 visits since.

|

|

|

|

|

Maki Cooperative School, Otari, Nagano, 2013 © Motohashi Seiichi

|

Motohashi's latest series, Arayashiki, captures communal living at the self-sustaining social welfare residence of that name, a place where people with handicaps and others who have stepped out of the societal mainstream either by choice or by circumstance live and farm off the land. Located in the remotest reaches of Nagano Prefecture, it was founded by a former teacher of the artist at Jiyu Gakuen, so Motohashi felt he was coming back to his own roots in studying this subject. His documentary film about the residence is titled Take Your Time -- Arayashiki.

Kinoshita Circus, Yokkaichi, Mie, 1979 © Motohashi Seiichi |

In 1972, Motohashi began providing photographs for a column on popular entertainment written for Taiyo magazine by actor Shoichi Ozawa, who was examining performing-arts forms that were newly emerging, in transition, or fading out as Japan's post-Olympics economic engine continued to surge, more people moved into cities, and regional modes of folk entertainment became tourist attractions. That collaboration lasted four years and continued when Ozawa carried on the series in his self-published quarterly Performance East and West. Of his circus shots Motohashi wrote, ". . . the landscape of towns and villages across Japan was changing virtually by the day. In exchange for everything becoming neat and trim and convenient, we gave up open spaces, and hours spent doing not much of anything at all. The circuses I encountered back then gave me a sense of comfort for the first time in a long time."

|

|

|

|

An ad describes the "swarm of new faces" amid the ranks of hostesses at a Ginza cabaret. On rainy days when business was slow, the women would hit the phones to draw clientele in. Cabaret (Cabaret Hollywood), Ginza, Tokyo, 1975 © Motohashi Seiichi |

|

Photo by Susan Rogers Chikuba |

After so many time-sweeping tales told in black and white, a stroll through the rolling green lawn, shaded groves, and countless blooms of the Clematis Garden adjacent to the museum feels intensely saturated in color.

All black-and-white images were taken by the artist and are provided courtesy of Izu Photo Museum.

|

|

|

Susan Rogers Chikuba

Susan Rogers Chikuba, a Tokyo-based writer, editor and translator, has been following popular culture, architecture and design in Japan for three decades. She covers the country's travel, art, literary and culinary scenes for domestic and international publications. |

|

|

|