|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Flaming Youth: Art Informel and Its Influence on Japan

Christopher Stephens |

|

Kazuo Shiraga, Ten'ansei seimenju (1960), Yamamura Collection, Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art |

A government white paper released in 1956 declared that "the postwar era is already over." This phrase, quickly embraced by the public, signaled that all of the efforts to rebuild the country over the previous decade or so had succeeded and it was now time to move into a new phase in Japan's history. A similar optimism took hold in the art world, prompted in large part by the French critic Michel Tapié.

In the early '50s, Tapié (1909-87) identified what he saw as a radical change in the nature of artistic expression. Tapié coined the term Art Informel ("unformed art") to collectively refer to a succession of international trends, such as abstract expressionism and lyrical abstraction, that opted for improvisational techniques and dispensed with traditional materials and notions of composition. Though his initial focus was on Europe and America, Tapié worked tirelessly to spread the word by organizing exhibitions throughout the world. His influence proved to be particularly strong in Japan, where his name is probably better known today than it is in the West.

A Feverish Era: Art Informel and the Expansion of Japanese Artistic Expression in the 1950s and '60s, running through September 11 at the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, revisits this eventful period in postwar history to trace the emergence of a uniquely Japanese approach to modern art.

|

|

Kanjiro Kawai, Vase (1962), National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto Collection |

To provide some context, the exhibition begins with works by people like Sam Francis and Lucio Fontana, who were among the 17 artists Tapié selected for a show titled Art of Today's World that toured Japan in 1956. Hailed by Japanese viewers, the event led to the widespread use of phrases like "Informel shock" and "Informel whirlwind" in the media. This in turn inspired Tapié to visit the country the following year and develop lasting relationships with Jiro Yoshihara (head of the Gutai Art Association) and Sofu Teshigahara (founder of Sogetsu-style ikebana). Together the men organized other exhibitions in Japan, and Tapié gave a number of young Japanese artists, particularly those associated with the Kansai-based Gutai group, their first international exposure.

The first of the Kyoto exhibition's four sections, "The Body, Action, and Flowing Lines," includes violent calligraphic pieces such as Yuichi Inoue's Work No. 9 (1955) and action-packed paintings like Kazuo Shiraga's Ten'ansei seimenju ("Dark Star, Blue-faced Beast" -- both epithets of Yang Zhi, a hero in the classic Chinese novel Water Margin) (1960). The works are so vibrant that one can practically see the artists splashing paint across the canvas -- or in Shiraga's case, madly smearing paint around with his feet. These methods are definitely worlds apart from the studious, detached approach favored by the Old Masters.

|

|

Taro Okamoto, Men Aflame (1965), National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo Collection |

The second section, "Primitivity, Life, and Ecological Images," focuses on abstract depictions of living creatures and beings. Kazuo Yagi's Bud (1964), for example, resembles a smooth ceramic coconut with the top and one side stripped away to reveal what looks like a nest of worms or a pile of brains. Taro Okamoto's painting Men Aflame (1955) is a riot of detached eyes, snaking lines, and distorted shapes rendered in bold primary colors. Though public monuments like Tower of the Sun (built for the 1970 Expo in Osaka) made Okamoto the era's most famous artist in Japan, he is relatively unknown abroad.

Along with paintings like Zenmei Takase's Mugen 36 (1964), consisting of hundreds of vermilion seals stamped on a black ground, the third section, "Repetition, Aggregation, and Covered Pictures," features photographs by Shomei Tomatsu that are filled with a colorful shower of seeds, petals, and leaves.

Sofu Teshigahara, Tree's Breast (1957), Sogetsu Foundation (photo: Yoshitaka Uchida) |

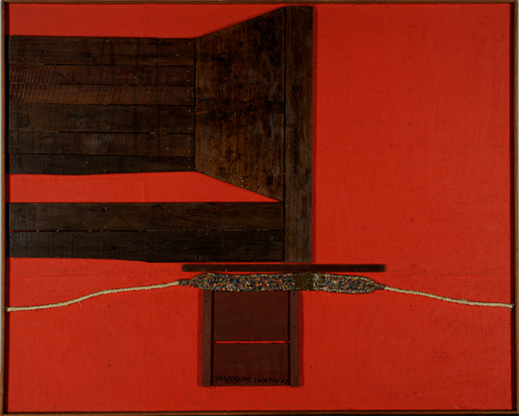

The exhibition concludes with "Material and Matter," a section that explores the use of unusual materials such as sand, tar, and fabric. Ko Nomura's Fissure-1 (1964) is a thick mass of layered newspaper, which is still readable but has the appearance of tough brown leather stamped with ghostly messages. A massive crevice runs through the middle of the work without revealing exactly what lies at the bottom.

As the exhibition's title suggests, this era in Japanese art, prior to the rise of Mono-ha and similarly conceptual pursuits, was distinguished by a sense of excitement and immediacy. Though some of the over 100 works on display have not stood the test of time, taken as a whole they deftly convey the social and artistic concerns of the day. The show also encourages us to reflect on what was essentially the first global art movement, and a period in which Japanese artists were integrating foreign styles and trends and striving to reach an international audience.

|

|

Shigeyoshi Iwata, Work - 139 (1963), National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto Collection

|

All images provided by the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto. |

|

|

Christopher Stephens

Christopher Stephens has lived in the Kansai region for over 25 years. In addition to appearing in numerous catalogues for museums and art events throughout Japan, his translations on art and architecture have accompanied exhibitions in Spain, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, South Korea, and the U.S. His recent published work includes From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and Gutai: Splendid Playground (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2013). |

|

|

|