|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

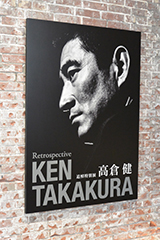

The Eyes Have It: Ken Takakura Retrospective at Tokyo Station Gallery

Susan Rogers Chikuba |

|

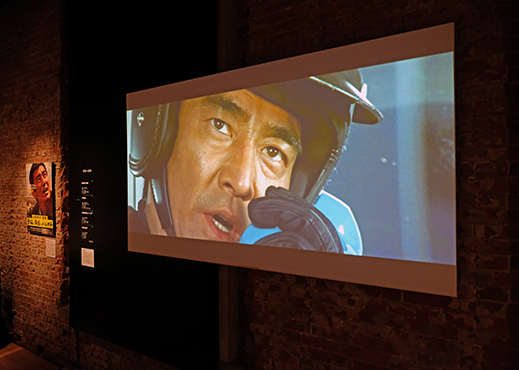

The exhibition opens with grainy close-ups of the actor and street shots of his movie posters by Daido Moriyama. Many of the roles Takakura played were men of few words whose eyes said it all. Photo by Jeff Amas |

Stories, stories, stories. We are inundated with them, and with others' reactions to and opinions about them. So kudos to Tokyo Station Gallery for offering a retrospective that's light on interpretive messaging and heavy on sensory impact. Whatever the cinematic icon Ken Takakura (1931-2014) means to you personally, and whatever new insights you gather from these exhibits on his lifework, you'll come away having felt the man, his time, his persona, his art.

Takakura's surprise line "And I do speak fucking English" in Ridley Scott's Black Rain (1989) is said to have inspired a new crop of students at English conversation schools across Japan. Other overseas productions he appeared in are Sydney Pollack's The Yakuza (1974), Fred Schepisi's Mr. Baseball (1992), and Zhang Yimou's Riding Alone for Thousands of Miles (2005). Photo by Jeff Amas |

"How to curate this was a real challenge, frankly," gallery director Akira Tomita told me the day before the exhibition opened. "Obviously cinema is an art, and a film can stand as a work of art. But our task was to present the legacy of a single actor. How do you split the public persona from the private man? Or separate the objective from the subjective? Ken Takakura made 205 films over a career that spanned 58 years and any number of roles. So we decided to present the full arc of his work as an artist -- that includes showing an excerpt from every film he made -- and let people see for themselves what view emerges."

Given Takakura's enduring star status, and the fact that 70 of those movies are not even commercially available, it's no surprise the museum has adopted a "by reservation only" admissions policy. Some of the films, recovered from long years in storage, were badly damaged; one exhibit introduces the scanning, cleaning, color correction, and repair efforts made during the 15 months of preparation.

|

|

Takakura debuted in 1956 at the peak of Japan's golden age of cinema, when film companies like Toei, Toho, and Shochiku were churning out 100 works annually. Photo by Jeff Amas |

The bulk of the show sits in the second-floor galleries, where Takakura's filmography is presented chronologically. The exhibits, which include scripts and photos from his estate in addition to the clips, are loosely grouped into six sections: the early, middle, and later years of his time under contract to Toei from 1956 to 1975, and the same for the remainder of his career working independently until his death in 2014.

Tomita, who watched 120 of the films in the planning process, pointed out that for Takakura's older fans, weekly outings to the movies were common. "For me, too," he said, "revisiting these works opened a window onto whole chapters of my life. A lot of memories came flooding back." Brief yearly timelines of key local and world events are provided in each section, a conceit that illumines cinema's place in Japan's larger history even as it enables viewers to approach and interpret the retrospective in a personal way.

|

|

The 1975 box-office hit Shinkansen daibakuha (The Bullet Train, Super Express 109) inspired the 1994 Keanu Reeves remake, Speed. For Takakura, who played the bad guy for once, it was a career turning point as he transitioned from a contract player to an independent actor with freedom to choose his roles. Photo by Jeff Amas |

Such is the meat and bones of the exhibition, and you could easily spend two hours taking it all in. The spirited heart of it, however, is found in the third-floor galleries, where works by two of Takakura's personal and professional admirers are showcased as a prologue to the filmography displays.

Daido Moriyama's photos, taken in 1968 and 1973, are noirish and fervent and capture the mood of the time, a period when Takakura had shot to fame in yakuza chivalry movies. His portrayals of the antihero who stands up to absurd injustices in order to protect those important to him resonated with wartime survivors and student protesters alike. Photo by Susan Rogers Chikuba |

The first space you'll enter is covered in images by photographer Daido Moriyama. The impact is arresting, gritty, charged with yang. A single glass stand holds a rare early copy of Yukon, Takakura Ken (Restless Spirit: Ken Takakura), a tastefully erotic tribute to the actor compiled in 1971 by Tadanori Yokoo and featuring the work of Moriyama and other leading lights of the postwar experimental arts movement.

A dramatic light-and-sound installation by Tadanori Yokoo uses trailers from 1964 to 1968 to give gallerygoers an impression of "Takakura's second coming." Those characters splashed across the far wall read "AT THIS THEATER SOON." Photo by Susan Rogers Chikuba |

The Yokoo connection veritably explodes in the next two galleries, with installations that the artist conceived and designed himself. In the first, trailers for six sword-swinging, street-fighting yakuza films of the mid-1960s play simultaneously over the four walls and ceiling in a stunning 16-minute loop that drives Takakura's dynamism right at you full-up and front-on.

Seven projectors are used to accomplish this in the 116-square-meter room. "At first, it was hard to envision what Yokoo had in mind," Tomita told me. "His concept was for people to feel as though they were inside Takakura. It took a lot of fine-tuning to get the timing and angles just right. I think most people will walk out of here feeling like they've just experienced something spectacular."

Yokoo's tribute shows a young Takakura when the actor's career was at full throttle. Low-budget films were at their peak production, and he was doing four or five a month. Photo by Susan Rogers Chikuba |

What with the flashing titles in chunky brushwork, fisticuffs, and blood-spurting blade fights swirling all around you and above -- this against a tumult of groans, yells, keening strains of enka songs, and Takakura's soft baritone growl as that chiseled body whirls in and out to dispatch villains and save the day -- well, yes, it absolutely is spectacular. Galvanizing even. After all that, it makes perfect sense to me that Yokoo next directs our attention to the cool, dark, and mysterious yin of waterfalls, tucked away in the gallery's intimate cupola space.

Ryuten (Flux), a mixed-media installation, is visceral, vertiginous, slightly terrifying to enter, and ultimately a highly personal and spiritual homage. Portraits of Takakura, who is known to have engaged in ascetic waterfall training, appear here and there among thousands of vintage waterfall postcards. Photo by Jeff Amas |

Takakura is remembered for his dark, brooding drifters, stoic tough guys, and heroic loners caught in the forever battle between love and duty. Hardened yet caring, courteous and aloof, such men of few words are often made out to be emotionally distant. But watch how he lets these figures speak with their eyes, the slightest twitch of a facial muscle, or, at times, silence. The subtlety says volumes.

The last display case holds Takakura's script for Kaze ni fukarete (Blowing in the Wind), a Yasuo Furuhata film about an elderly hunter, living alone, who in his final days begins to reach out to people he has known. It was never made: Takakura passed away just months before production was to begin. Nearby sits the trunk he used when filming abroad for Umi e -- See you (1988). That's a quiet piece of poetry that surely would have won the man's knowing nod of approval.

|

|

|

|

Admission tickets cannot be purchased at Tokyo Station Gallery for this exhibition. Reservations can be placed online, by phone, or at Lawson Ticket, Ticket Pia, and JTB shops. Call 03-5777-8600 or see the gallery website for details. Left photo by Jeff Amas; right photo by Susan Rogers Chikuba |

All images are by permission of Tokyo Station Gallery. |

|

|

Susan Rogers Chikuba

Susan Rogers Chikuba, a Tokyo-based writer, editor and translator, has been following popular culture, architecture and design in Japan for three decades. She covers the country's travel, art, literary and culinary scenes for domestic and international publications. |

|

|

|