|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese residents of Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Masato Otaka and his Philosophy of PAU

James Lambiasi |

|

Masato Otaka explaining the Sakaide Artificial Ground Project, 1966. (Property of the National Archives of Modern Architecture) |

Many can say they are familiar with the Metabolism movement in Japanese architectural history. Important architects like Kenzo Tange and Kiyonori Kikutake come to mind, or the iconic image of Kisho Kurokawa's Nakagin Capsule Tower. Of the seven original Metabolists who introduced their philosophy at the 1960 World Design Conference in Tokyo, however, we are less familiar with architect Masato Otaka (1923-2010). Fortunately we are now able to understand his oeuvre in meticulous detail through an exhibition highlighting his life's work, Uniting Architecture and Society: The Approach of Otaka Masato. Currently showing at the Agency for Cultural Affairs's National Archives of Modern Architecture in Tokyo, this is an extensive collection of his sketches, plan drawings, and models that have fortuitously been preserved for over a decade.

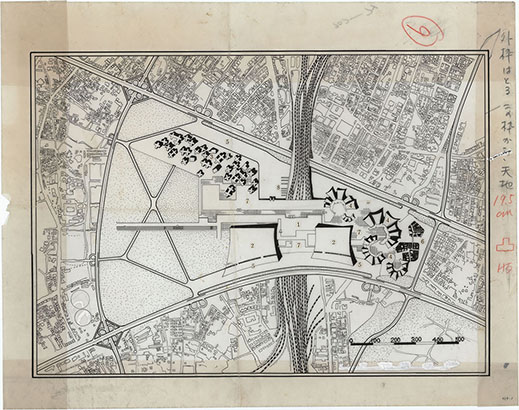

Although Otaka did not reach the level of international fame of some of his other Metabolist colleagues, through this exhibition we are able to identify key elements of his philosophy that are nevertheless of great importance. Exhibits of his works are organized into three sections, starting with his formative years as an architect, going on to understand his work as art and prefabrication, and concluding with his urban projects. Given that he began his career as an employee of Kunio Mayekawa, one might first understand how his work was influenced by Mayekawa and in turn Mayekawa's own mentor, Le Corbusier. From early on, Otaka's interest in taking advantage of the new technology of reinforced concrete to create new physical forms and urban environments is clear. A collaborative project with Fumihiko Maki, the Shinjuku Subcenter Project based on the Group Form Concept, introduces a very Metabolist idea of defining irregular spaces through loose groupings of buildings as opposed to rational street spaces. His daring move to extend a park over the train lines also introduces the artificial ground plane, something that would evolve into a very important aspect of his work.

|

|

Shinjuku Subcenter Project based on the Group Form Concept, 1960, in collaboration with Fumihiko Maki. (Property of the National Archives of Modern Architecture) |

When Otaka opened his own office in 1962, he was able to articulate his philosophical goals through his acronym PAU, standing for Prefabrication, Art & Architecture, and Urbanism. In the housing development Sakaide Artificial Ground he employed new concrete building methods to invent a new urbanism. In order to separate buildings from the rational street grid, he created an artificial ground plane six to nine meters above grade, which allowed the buildings above grade to interact in a more flexible manner, free from interaction with the vehicle.

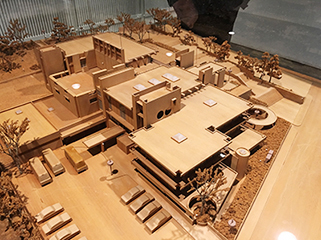

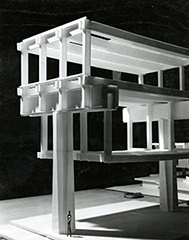

His achievements in prefabrication are evident in his Chiba Prefectural Library, in which precast and pretension concrete beams are assembled at site. In parallel with developing this new technology, Otaka in fact develops a new architectural aesthetic as well. Rather than hide the fact that elements are prefabricated, the desire to showcase pieces coming together, like a big Tinkertoy set, leaves its mark on his work. His adroitness in prefabrication is even further refined in the Tochigi Prefectural Council Building, where prefabricated elements actually hang from a larger mega-structure and highlight the organic nature of Metabolist design.

|

|

|

|

Wooden model of the Chiba Prefectural Library, 1968. (Property of the Chiba Prefectural Library) |

|

Tochigi Prefectural Council Building (1966). (Photo by Osamu Ishizaki; property of the National Archives of Modern Architecture) |

The third and final section of the exhibition focuses on his urban planning work. In addition to architectural design, Otaka was able to concentrate efforts on the planning level as well. This included overseeing committees, participating in boards to draft new urban regulations, and developing urban programs. Therefore, while one might not know the name Masato Otaka, one is likely to be very familiar with his urban project achievements. The Tama Center Station Plaza and Pedestrian Deck is one such project, as is the Yokohama City Center Waterfront Redevelopment, better known as Minato Mirai 21.

Centrally located in the exhibition is a very large model of the Motomachi Apartments, a huge housing complex in Hiroshima that was built to replace the "A-bomb slums" that sprang up in the aftermath of the atomic bomb devastation of World War II. The complex itself encapsulates all the philosophical goals of PAU, as the prefabricated architectural elements combine to create a futuristic urban space hovering above the vehicular ground plane. As emphasized in the model, it is located conspicuously on axis with the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, which to an urban planner today might seem too strong a position for a residential apartment building. Perhaps it is this awkwardness that generates such a poignant image, in that one is given to understand that the era in which Otaka created his work was a time of movements imbued with philosophical reactionism. To an observer today, his work might have the ubiquitous appearance of so many of the dated concrete buildings found throughout Japan. My hope, however, is that visitors to this exhibition might appreciate the understated strength of Otaka's ideas, many of which thread through our perception of modern design today.

|

|

|

|

Axis view of Motomachi Apartments, Hiroshima, 1969-78. (Model production: Hiroshima University) |

|

Overview of the exhibits. All of the explanatory text is in Japanese and English. (Photo by James Lambiasi) |

All images by permission of the National Archives of Modern Architecture, Agency for Cultural Affairs. |

|

|

James Lambiasi

Following completion of his Master's Degree in Architecture from Harvard University Graduate School of Design in 1995, James Lambiasi has been a practicing architect and educator in Tokyo for over 20 years. He is the principal of his own firm James Lambiasi Architect, has taught as a visiting lecturer at several Tokyo universities, and has lectured extensively on his work. James served as president of the AIA Japan Chapter in 2008 and is currently the director of the AIA Japan lecture series that serves the English-speaking architectural community in Tokyo. He blogs about architecture at tokyo-architect.com. |

|

|

|