|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese residents of Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Yayoi Kusama: All the Stars in the Sky

J.M. Hammond |

|

UNBEARABLE WHEREABOUTS OF LOVE (2014), My Eternal Soul series, acrylic on canvas, 194 x 194 cm. © Yayoi Kusama |

Yayoi Kusama's huge yellow and black pumpkin sculptures can be spotted in the most unlikely of places across Japan, and now one stands outside The National Art Center, Tokyo. It's there as part of her large-scale retrospective My Eternal Soul, which brings together over 250 works spanning her entire career.

Kusama, alongside artists such as Takashi Murakami, has become one of the faces representing Japanese contemporary art internationally, especially since the turn of this century and a major show at the Tate Modern in London, which sparked a run of exhibitions across the globe. In 2014 one of her works was sold at auction at the highest price for any living female artist.

Kusama began experiencing visual and aural hallucinations as a child, and this has played a large part in her art, and in her artistic mystique. These canvases can offer a personal, private world of imagery in a similar way to "outsider" artists, who like, Kusama, see the world in their own idiosyncratic way. But although her work is sometimes included under this heading, unlike these outsiders, Kusama works within, rather than outside, the spinning wheels of the monetized art world.

Broadly speaking, the exhibition is divided into two parts -- the first in a huge central area showcasing her My Eternal Soul series of large-scale paintings executed over the last decade; and, in smaller galleries and rooms surrounding this space, a look at her activities during earlier periods of her life. In addition, three other works join the above-mentioned mixed-media sculpture of the pumpkin outside the museum's walls.

|

|

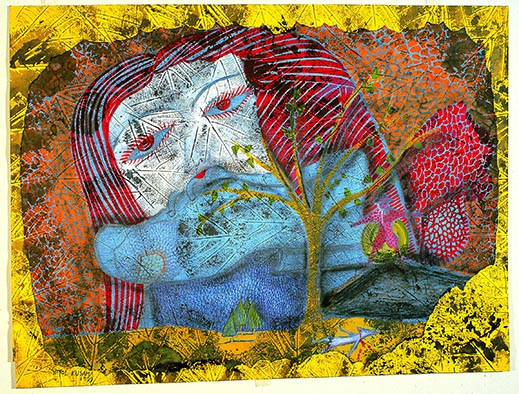

I Who Committed Suicide (1977), ink, ball-point pen, watercolor and collage on paper, 39.5 x 54 cm, The Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo. © Yayoi Kusama |

The title of the series points to Kusama's concern with such themes as life, death and love in the works on display, which number well over a hundred. Acrylic being her medium of choice here, the colors are often vibrant, and many of the canvases are packed with detail.

Size as well as scale plays a part in the room's undeniable impact. Kusama started the series with canvases of different sizes, but soon settled on a standard format of 194 x 194 cm, and these are hung in rows of two along both long walls of the room (three high along the shorter end wall).

Many visitors to the exhibition seemed to surrender themselves to experiencing the works as a whole -- at least as an initial reaction, before observing them up close. As photography is allowed in this room, but not elsewhere in the exhibition, a festival mood prevailed as people took colorful selfies in front of the paintings.

Viewers may be tempted to look for patterns linking some of these works, and some correspondences can certainly be found. Where in many earlier works, dots were everywhere, here tiny human eyes repeated endlessly function in a similar manner. Indeed, the pieces could almost be approached as a kind of puzzle: you could contemplate the meaning of the title given each work, and how it corresponds to the images you see in front of you. You could try to decipher all the various elements, figurative or abstract, in each individual picture, or try to work out how similar motifs relate to each other across paintings.

For example, the teacup, boot and eyeglasses in Abode of Happiness, when seen in isolation, could suggest the small domestic pleasures of life. Yet when the same elements appear again in The Silvery Universe they form part of a more cosmic scenario.

|

|

Pumpkin (2007), mixed media, 450 x 500 cm, Forever Museum of Contemporary Art. © Yayoi Kusama |

Moving away from this kind of densely-packed imagery, a number of paintings, particularly those from around 2015-16 (the most recent works in this section), reveal simpler compositions with bigger, open shapes. One of these shapes is an irregularly-outlined square design taking up most of the frame. Tempting as it may be to look for patterns in the use of a particular shape (or color, or color combination), any given element can appear again elsewhere in a different guise -- and this uneven square motif is used, alternately, to convey the ideas of the heart, death, emancipation from sorrow, and the soul -- all related, but not identical concerns.

If Kusama, now in her late eighties, seems to have a preoccupation with death, this could understandably be seen as a natural concern for someone entering her twilight years. Yet as the next room demonstrates, Kusama was making works from at least her twenties that show a concern with mortality.

Her hallucinations also began at an early age, and her taking up art was a way to deal with and overcome them, particularly through the repetition of simple forms such as the polka dot -- an attempt to obliterate the gap between the self and the universe.

Endless repetition is at the core of the Infinity Net paintings she began executing after she moved to America in the late 1950s. Here, she seems to have spread the paint over the canvas thickly and then scraped or chipped it away in tiny repetitive nicks to reveal the ground beneath. While these marks lack the even roundness of the dots she later became associated with, they could certainly be seen as a precursor. Alongside some works entirely in white, three red canvases reveal, through these holes, the depths beneath: in two cases this takes the form of a rich black, while in the other it is the unprimed off-white canvas itself.

Kusama went on to develop this aspect of her art, as is evident in a short film from 1967 being screened here. In Kusama's Self-Obliteration the artist covers herself, as well as the horse she is riding on, with dots. She also obliterates a cat -- but luckily for the feline, only with a patchwork of leaves.

|

|

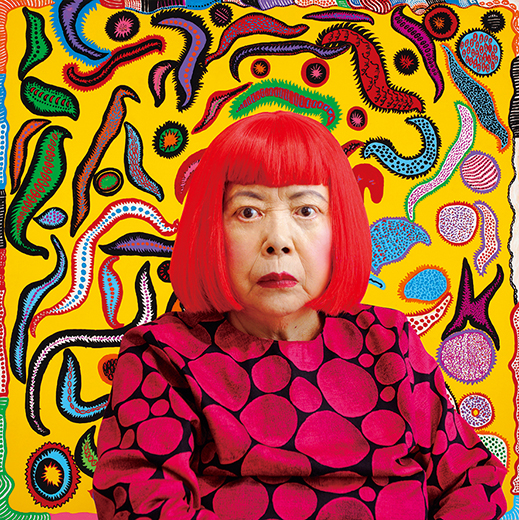

Portrait of the artist. © Yayoi Kusama |

Where a retrospective of an artist's career often reveals development and change as much as constant or recurring themes, in Kusama's case the latter tendency is pronounced. This year's Dots Obsession, a mixed-media installation featuring white mannequins plastered with red dots, explores the same fixation as her film from five decades ago.

Back in those days, Kusama was both a key figure in the New York underground art scene and active in protests against war and the commercialization of culture. In more recent years too, she has been known to question art's close ties with money -- at one biennale she set up an installation of countless balls and then proceeded to sell them off cheaply, one at a time, to the audience. Yet such antics haven't stopped her fully participating in the full-scale commercialization of her own art. Her polka dots may suggest infinity in the cosmic sense, but they are also infinitely reproducible -- on everything from cases for smartphones to boxes of cookies.

The exhibition comes to an end with an installation of a line of furniture modeled on her yellow and black pumpkin motif, a not-so-subtle hint for the audience to prepare to turn into customers, and (as the street artist Banksy has phrased it) to exit through the gift shop. The line of customers there was so long that some people likely spent as much time waiting to buy their Kusama-themed goods as they did in the exhibition itself. Such is the uneasy alliance between art and commerce in 21st-century Japan.

It's also notable, however, that the vast majority of the actual art pieces, particularly the more recent ones, are from the collection of the artist herself, not from museums or private owners, suggesting Kusama's deeply personal connection to her artistic output. As My Eternal Soul demonstrates, this output has been, and continues to be, prolific, imaginative and energetic.

|

|

|

|

J.M. Hammond

J.M. Hammond researches modernity in Japanese art, photography and cinema, and teaches in Tokyo, including as a faculty lecturer in the English department at Meiji Gakuin University. He has written about art for The Japan Times for over a decade. His essays include "A Sensitivity to Things: Mono No Aware in Late Spring and Equinox Flower" in Ozu International: Essays on the Global Influences of a Japanese Auteur (Bloomsbury, 2015) and "The Collapse of Memory: Tracing Reflexivity in the Work of Daido Moriyama" for The Reflexive Photographer (Museums Etc, 2013) [reprinted in the same publisher's 10 Must Reads: Contemporary Photography (2016)]. He has given various conference papers, including at the University of Hong Kong and the University of Oxford. |

|

|

|