|

|

|

HOME > FOCUS > Legacies of the Man Who Sculpted Wind from Trees, at the Museum of Modern Art, Hayama |

|

|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese residents of Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Legacies of the Man Who Sculpted Wind from Trees, at the Museum of Modern Art, Hayama

Susan Rogers Chikuba |

|

The 20 or so sculptures by Ainu artist Bikky Sunazawa on exhibit are rightly given plenty of space across three rooms, a generosity that suits the transcendent connections he sought through his art. Photos by Susan Rogers Chikuba |

The masterwork stands -- or rather, abides -- alone in the center of the first gallery of Sunazawa Bikky: Sculpted Spirits in Wood, a show running through 18 June at the Museum of Modern Art, Hayama. Tongue of God is at once erotic, comical, wild; at rest and yet very much alive. Two meters high and more than half that around, it's a solid mass of oak that looks so natural one wonders if it was brought in from the woods as is. Closer inspection reveals that its cracked and weather-stained surface is covered in thousands of rhythmic, tightly flowing dimples shaped by a chisel. The rippling caresses invite us to reach out and touch it. Unfortunately, this is not allowed.

|

|

|

|

|

Tongue of God (1980) was one of the first pieces Sunazawa made in his last and most beloved studio, a former elementary school set amid deep forests in northern Hokkaido. Photo by Susan Rogers Chikuba

|

The sculpture is said to resemble the tapered end of the ikupasuy, a prayer stick used in Ainu rituals to communicate with the gods. The tongued portion of that instrument is typically carved with a design that identifies the worshipper. Sunazawa's monument seems an apt mediator for an individual who was larger than life and whose gift was expressing, in abstract form, a mythology derived from Ainu traditions yet driven by his own poetic visions. In Ainu folklore, oak is a benevolent tree spirit that's willing to provide assistance. Indeed, Tongue of God seems to hum expectantly as you stand before it. It's held in the permanent collection of the Sapporo Art Museum, but is only occasionally brought out on display, and even less frequently lent out for tours. Take this opportunity to converse with it in Hayama if you can.

|

|

|

|

|

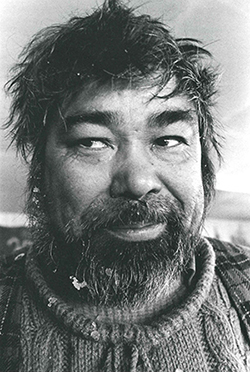

Bits of ice and frozen chips of wood would fly as Sunazawa worked on logs with axes and chisels in his Otoineppu atelier. He likened his intense physical interaction with his material to a sensual relationship and considered his studio a "place to make love to the wood." Photo by Ruiko Yoshida

|

Born in 1931 to parents who were leaders in the movement for Ainu land and civil rights, in his late teens Sunazawa worked with his family and other households to establish a new settlement. At day's end he would sketch the cattle and horses. "In the beginning I just wanted to draw a horse as it was and capture its sturdiness and strength. But the more I drew, the more I wanted to capture the essence of the horse -- and eventually the animals I drew turned into abstract forms." Leaving Hokkaido for Tokyo at the age of 21, he became caught up in the avant-garde art world of the 1950s and '60s. Of this time he later wrote, "I learned more from the free-spirited conversations with artists than from anything else . . . We were of the same opinion that a work can't be called art if it doesn't have eroticism in it." By the 1970s he was back in Hokkaido and involved in the Ainu liberation movement. (Quotes from Asu o tsukuru Ainu minzoku [The Ainu Who Would Create Tomorrow] by Tsutomu Yamakawa, 1988, and a personal correspondence to filmmaker and graphic artist Katsumi Yazaki, 1981)

|

|

|

|

|

Nude (1) (1980); photo by Tadasu Yamamoto. Many of Sunazawa's nudes are compiled in the luscious tome North Women, published by Yobisha in 1990. |

| |

|

|

|

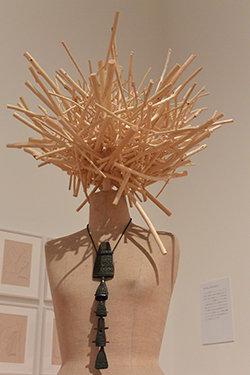

A shaved branch tufted at one end, the inaw is another ceremonial implement that influenced Sunazawa's designs. The Ainu believe that after receiving a prayer it turns into a bird. Sunazawa envisioned its shape both as birds and as wooden flowers, and presented these forms as heads. Woman with a Wooden Head (detail, 1983); photo by Susan Rogers Chikuba

|

Sunazawa's graphite and watercolor nudes, 22 of which are on display in this show, reveal his playfulness and fascination with the sensual. One also sees in them the lines of tree limbs and the girthy forms of logs and stumps, the raw material of his sculptures. Like them, his drawings seem steeped in a vision of nature that goes beyond physical form to address the spirit-life it's endowed with.

Sunazawa was a proponent of participatory art, a stance rooted in the Ainu belief that all things in nature, animate or otherwise, have kinship. He believed that sculptures should be touched, and that one's tactile sense would lead to a different, even transcendent, way of "seeing" the work. He would sometimes cover his creations with a black cloth and let people explore an exhibition hall with their hands alone -- to literally grasp, in a sight-centric world, the deeper meaning of what it is to be human. His hope was to stimulate the senses that are more often used by animals. In 1982 he debuted his Juka (Wooden Flower) series by preparing truckloads of stripped willow branches for viewers to affix to a tree, rather like birds preparing a nest.

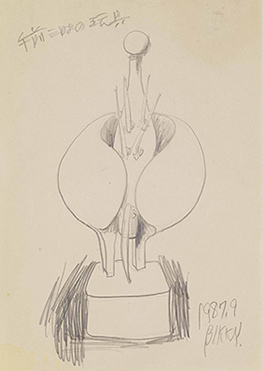

Sunazawa believed that through his woodworking, and as a part of nature himself, he was giving new life to the spirit of a fallen tree. Like the tree's gift of material, his visions were sometimes decades in the making. Toy of Three in the Morning, a series named for the hours before daybreak when he did most of his work, is a collection of whimsical insect-like forms he produced in earnest from the mid-1980s but which can be traced to Aoi sakyu ni te (In Blue Sand Dunes), a collection of prose and poems he published in 1976. The book, in turn, was inspired by images that had come to him in dreams as early as 1964. In contrast to his bold sculptures with textured surfaces that show signs of his axing and adzing and chiseling, these smaller works have smoothly polished finishes and deftly engineered movable parts.

|

|

|

|

Drawing and finished work from the Toy of Three in the Morning series (1987). The wee hours were when the normally gregarious Sunazawa would turn inward. It was his habit to sketch from 11 p.m. until 3:30 a.m., when the sound of the limited express on its run from Sapporo to Wakkanai would signal him to begin carving. Left photo by Tadasu Yamamoto; right photo by K-Photo Service |

If Sunazawa were still alive perhaps we would be allowed to touch the sculptures on display. But we can take consolation in his assurance that the power of the tactile sense is there, in us and inhabiting his works. "The more you focus on [it], the more endless the concept becomes. It eventually becomes visual. Its point of view is always there," he wrote in "Hands," a 1988 catalog essay.

In the pair of sculptures Northern King and Queen (1987), each has a trio of spheres with complementary inside-out volumes. Feelers protruding from the head of the female figure suggest receptivity. Photo by Susan Rogers Chikuba |

Throughout his life Sunazawa struggled to reconcile his deep pride in being Ainu with the narrow routes of creative expression available to an indigenous man in Japan -- namely, carving traditional art or crafting objects for the tourist trade. In 1983 he was 51 and feeling disillusioned by the prospects available to him outside of Hokkaido. A three-month prefectural scholarship for artistic exchange, and a serendipitous meeting with a University of British Columbia professor who was an expert on legal matters concerning First Nations peoples, set him on a path that would bring new insight.

Sunazawa accepted an invitation to work in the Granville Island studio of Haida carver Bill Reid, one of Canada's most revered artists. While in Vancouver he saw the art of many Northwest Coast First Nations people showcased in lavish books and fetching high prices at galleries. The experience freed him from the received notion that his indigenous identity was a liability to furthering his creative expression. He also traveled to Tsimshian Gitksan settlements on the Upper Skeena River, where he saw totem poles from the late 19th and early 20th centuries next to those more recently erected. He described the sight of them in their natural setting -- cracked and split, scarred by the elements, some fallen and covered with moss, all in various stages of their return to nature -- as "terrifically magical." It inspired him to create outdoor sculptures in wood so that natural phenomena would finish and then reclaim the work. He returned to Otoineppu with renewed vigor, confident that he could be both a contemporary sculptor and an Ainu one.

|

|

In Listening to the Wind (1986), an installation piece made for an exhibition at the Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art, four abstract figures bend in the way of the tree they inhabited. Sunazawa specified that the composition be arranged freely each time it is shown, to suggest different tales. Photo by Susan Rogers Chikuba |

In the autumn of 1988, in great pain from the cancer that would end his life short months later, Sunazawa wrote his most celebrated poem. It is both a love letter and a plea to the four winds of the North, South, East and West:

|

Wind,

You four-headed, four-legged beast

Your fury

Makes people love

Your interludes

Which they call the seasons

I pray, blow your strongest

Upon me, all of me

And then directly into my eyes

Wind—

Because you're a four-headed, four-legged beast

I'll give you

A lovely set of customized pants

Then

Won't you hold me, just once?

|

Translation by Susan Rogers Chikuba

|

Always sketching and playing with words, Sunazawa indulged his creative passions right to the very end. In January 1989 he famously traveled, on special reprieve from his doctor, from his bed at Asahikawa University Hospital to Kanagawa for the opening of the Contemporary Artists Series exhibition, where he directed the installation of his works from a wheelchair and made a brief speech. He died in Asahikawa four days later. His last words, written minutes before he passed, were "My disease is cured." It's said that during the Kanagawa show several of his sculptures sprouted mushrooms, a testament to his belief that nature would complete his work.

In 1987 two amateur astronomers from Hokkaido discovered a minor planet they named "Bikki" after the artist. At the time of this writing, a running list of sightings hosted by the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory shows that Sunazawa's celestial namesake was last observed on 24 May 2017, from Mauna Loa. As it and the other planets continue to turn, his Otoineppu atelier remains open, housed in a venue now called Eco Museum Osashima. Sunazawa's works can also be found in the collections of the Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art, Sapporo Art Museum, Hokkaido Asahikawa Museum of Art, and Toyako Museum of Art. At Hayama, special events related to the exhibition will be held on 3, 10, and 17 June.

Headlines and social network posts today are increasingly filled with the voices of indigenous people around the world, as greater recognition is sought for their wisdom and teachings. And yet Sculpted Spirits in Wood is, nearly three decades after Sunazawa's death, his first solo show to make it to a museum outside of Hokkaido. The time is ripe for a full retrospective.

All images are by permission of the Museum of Modern Art, Hayama.

|

|

|

Susan Rogers Chikuba

Susan Rogers Chikuba, a Tokyo-based writer, editor and translator, has been following popular culture, architecture and design in Japan for three decades. She covers the country's travel, art, literary and culinary scenes for domestic and international publications. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|