|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese residents of Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Plant Life: The Botanical Illustrations of Kawahara Keiga

Christopher Stephens |

|

Stauntonia hexaphylla (Thunb.) R. Br. (c.1824-1828) |

The artificial island of Dejima, located in Nagasaki Bay, was built in 1634 as part of the Japanese government's isolationist policy. With an area of 1.5 hectares and a single bridge connected to the mainland, the fan-shaped island was established as the only site for foreign trade in the country, housing Portuguese merchants for the first few years and the Dutch for the following 200 years, from 1641 to 1859. In principle, the inhabitants, who never exceeded 20 in number, were not allowed outside the gate, and the local Japanese, with the exception of those who performed services such as cooking, interpretation, and prostitution, were prohibited from entering the compound.

Among those with access to Dejima was Kawahara Keiga (c.1786-c.1860), an artist who began selling his works to Dutch traders in 1811. Since they were not allowed to travel freely, foreign residents were eager to learn more about Japanese customs and landscapes. This inspired Kawahara to make series of pictures depicting everyday events like childbirth, marriage, and funerals. Outside Dejima, Keiga's status attracted Japanese customers, who were similarly intrigued by foreign life. In addition to portraits, scenes of people dining and drinking, playing billiards, and performing dramas proved to be especially popular. Then, due to a fortuitous encounter with a German doctor, Kawahara branched out into botanical illustrations.

Currently on view at the Shimonoseki City Art Museum in Shimonoseki, Yamaguchi Prefecture is The Botanical Illustrations of Kawahara Keiga from the Collection of the Russian Academy of Sciences Library: Japan through the Eyes of Siebold, an exhibition set to travel to the Ibaraki Ceramic Art Museum in Kasama, Ibaraki Prefecture in the fall before a final stop at the Panasonic Shiodome Museum in Tokyo next January. The show focuses on the pictures Kawahara was commissioned to make by the German physician Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796-1866) and is rounded out with some of the artist's earlier works and related documents.

|

|

Ilex latifolia Thunb. (c.1824-1828) |

Posted to Dejima by the Dutch government in 1823, Siebold brought professional skills that were of great interest to local officials, giving him a freer hand than many of his compatriots. He was invited to leave the island to demonstrate Western medical practices and open a small school, where he trained some of Japan's earliest Western-style doctors. His daughter, Kusumoto Ine, later became the first female doctor in the country, eventually serving as personal physician to the Empress.

An avid natural historian, Siebold spent much of his time observing and cataloging plant and animal life. To document his findings, he enlisted Kawahara to produce more than a thousand works over a four-year period between 1824 and 1828. Many of these appeared in Siebold's books Nippon (1832-1851, 20 volumes), Fauna Japonica (1833-1850, five volumes), and Flora Japonica (1835-1870, 30 volumes), vast compendiums of textual and visual data that gave the outside world its first in-depth look at the mysterious nation.

Siebold's influence is nowhere more apparent than in the dozens of scientific names that are derived from his surname. These include Acer sieboldianum, a type of maple, Tsuga sieboldii, a variety of hemlock native to southern Japan, and Magnolia sieboldii, a magnolia found in Japan as well as southeast Asia. During his time in Japan, Siebold shipped thousands of plant specimens, many still living, back to the West. He is credited with establishing tea cultivation in Java by smuggling Japanese tea seeds to what was then the Dutch East Indies, and blamed for introducing Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica) to Europe -- the plant was initially embraced as a beautiful addition to the garden, but is today reviled as a highly invasive, noxious weed.

|

|

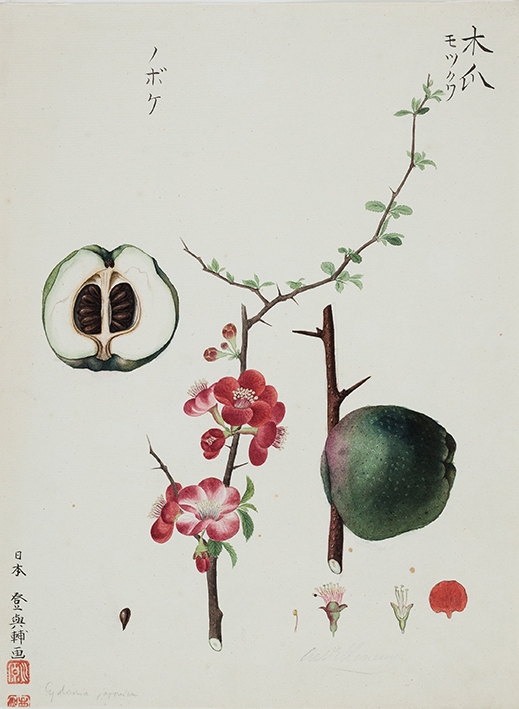

Chaenomeles japonica (Thunb.) Lindl. ex Spach (c.1824-1828) |

Though greatly impressed by Kawahara's skills, Siebold asked that the Dutch painter Carl Hubert de Villeneuve be dispatched to Dejima to give the artist a grounding in Western art. Combining these techniques with the traditional Japanese methods he had learned from his father, also a painter, Kawahara forged a style that recalls European natural history books of the era while remaining distinctly Japanese. His acutely observed, exquisitely detailed illustrations stand as accurate renderings of his subjects but also as stunning works of art.

Kawahara's standard approach was to depict a single branch of a given plant, usually in bloom, in the center of a blank plane. Then, at the bottom or off to one side, he added each element of the flower and each stage of its growth. Some works include the plant's roots, seeds, and fruit -- shown on the branch, separate, and in section. In most cases, the specimens were labeled in katakana script in the upper left of the sheet, kanji characters in the upper right, and signed with two vermilion stamps in the lower left. When Kawahara diverges from this formula, the results are even more eye-catching. Though most of the leaves and flowers are meticulously painted and shaded, some are simply outlined in sumi ink as if they were forgotten or left unfinished. This creates a striking visual contrast while highlighting veins and other details that might otherwise be overlooked. In Kawahara's Laurocerasus zippeliana, the leaves are so large that they extend well beyond the edges of the paper, and one is shown in the grip of three uncolored fingers (the only sign of human intervention in the exhibition), conveying a sense of scale. In what is perhaps the most memorable work in the show, Kawahara depicts a wax gourd (Benincasa hispida) attached to a flowering plant in the center of the picture with two detached yellow blossoms (one open, one closed) underneath. In the background there is an outline of a huge gourd, pushing the work beyond subjective observation into artistic innovation.

|

|

Benincasa hispida (Thunb.) Cogn. (c.1824-1828) |

Siebold's relationship with Kawahara came to an end in 1828, when, having completed his mission in Dejima, the doctor set sail for Java. He didn't get far, though. A storm caused the ship to run aground near Nagasaki and Japanese authorities discovered forbidden articles, primarily maps, in the 80 or so crates Siebold was attempting to take back with him. He was arrested, along with Kawahara and many of his other associates, returned to Dejima, and expelled from the country the following year. Kawahara, meanwhile, was subsequently released and published his own botanical encyclopedia in 1836, only to be arrested again several years later for depicting family crests in a picture of Nagasaki Port that was commissioned by a Dutch merchant. He was dismissed from the city, but a group of paintings at a local temple that bear his signature suggest that he returned at some point. Kawahara's later activities and the circumstances of his death remain unknown.

On an official visit to Japan in 2016, Russian president Vladimir Putin presented Prime Minister Shinzo Abe with a volume of Kawahara's botanical illustrations from the Russian Academy of Sciences Library in St. Petersburg. This is where the 125 works in this exhibition -- as well as the rest of Kawahara's 1,000 botanical works -- have resided since the 1860s, making the show a rare opportunity to experience a singular artist and relive a defining era in Japan's history.

|

|

Wisteria brachybotrys Siebold et. Zucc. (c.1824-1828) |

All images by Kawahara Keiga, provided by the Russian Academy of Sciences Library, St. Petersburg, 2017; reproduced courtesy of Art Impression.

|

|

|

Christopher Stephens

Christopher Stephens has lived in the Kansai region for over 25 years. In addition to appearing in numerous catalogues for museums and art events throughout Japan, his translations on art and architecture have accompanied exhibitions in Spain, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, South Korea, and the U.S. His recent published work includes From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and Gutai: Splendid Playground (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2013). |

|

|

|