|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese residents of Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Revelations: Wood Sculptor Takeki Fujito at the Sapporo Art Museum

Susan Rogers Chikuba |

|

Takeki Fujito with the series Okami to shonen no monogatari (Tale of a Boy and Wolves), a fable told in 17 verses and 19 carvings. He created it for this exhibition so that present and future generations can learn about the Hokkaido wolf, the Ainu people’s relation to it, and its extinction at the hands of late-19th century settlers. |

When Ainu woodcarver Takeki Fujito rests a hand on one of his finished works, he appears like a grandfather tousling the hair of a beloved child. Like many craftsmen he's not quick to speak. But as the ready spark in his eyes suggests, once the 83-year-old opens up his stories flow warmly, as full of life as the mythic yukar legends he heard at the knee of his grandmother and other elders from his childhood who knew and upheld the old ways.

|

|

|

|

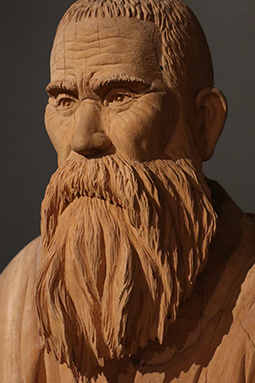

| Fujito Take zo (detail, 1992, camphor) is a life-sized statue of Fujito's grandmother, who raised him. |

|

Kawakami Konusa zo (detail, 1993, camphor) brings his great-grandfather to life. |

Some 70 years have passed since Fujito started carving bears at age 12 under the strict, even harsh, tutelage of his itinerant craftsman father. The retrospective now at Sapporo Art Museum through 17 December shows the full breadth of that career, in loosely chronological chapters that unfold to reveal a man coming home to himself while ever deepening his craft.

|

|

|

|

|

Jurei Kannon zo (Tree-spirit Guanyin; detail, 1969, Japanese yew). When he received this commission Fujita traveled to Kyoto and Nara and spent a week poring over Buddhist statuary. The work is enshrined at Shotokuji temple in Lake Akan, Hokkaido.

|

The exhibition opens with early carvings like the 1964 Ikari-guma (Angry Bear) and Jurei Kannon zo (Tree-spirit Guanyin), the commission that propelled Fujito out of the tourist trade into the art world. Made at the request of his earliest patron, who had taken over the helm of the lumber and land-lease company run by her late husband in Lake Akan, the statue is not only the deity of compassion but also an avatar for reposing the souls of trees cut in the early days of the firm's history.

The show ends with the debut of a new series, a fable about the Hokkaido wolf told from the Ainu perspective in 17 vignettes. In between are galleries filled with Fujito’s stop-action carvings of animals in the wild, his memorials to Ainu ancestors, and, of course, his celebrated bears, in guises from the comical to the fierce. We see them also in the unique role they played in the lives of the Ainu, who worshipped them as gods.

|

|

A screen grab from the exhibition's introductory video shows Fujito at work shaping the details of fur and rippling muscles. He is known for the lifelike movement he introduced to the bear-carving genre. ©Sapporo Art Museum |

"Bears taught me everything I know about carving." A realist, Fujito is renowned for the fine detail of his works -- right down to the twitch of a muscle or the pile and nap of an animal's coat. He never sketches his designs, working instead from his sense of the wood and what it holds, drawing out the image he sees in his mind with an arsenal of tools that fill his studio walls and drawers. For large works, the physical crafting might begin with a chainsaw or broadaxe, progressing to an array of smaller axes, chippers, gouges, chisels, awls and fine blades.

But the creative process starts earlier, with Fujito's first encounter with the tree -- whether a live one in the forest, a fallen log, or a piece of bogwood. "I'm working with material -- a life -- that was hundreds of years in the making. I have to do right by that," he says. Before cutting, he performs a kamuy no mi prayer ceremony to acknowledge his receipt of the forest's gift.

|

|

Connections between parent and child are a frequent theme for Fujito, who lost his mother when still an infant and whose relationship with his father was difficult at best. In Oyako-guma (Parent and Child; detail, 1994, camphor), a mother bear offers patient presence to her upset cub. |

So many of Fujito's works have a narrative quality to them -- a much larger drama captured in one telltale moment. I asked how his ideas come to him -- in dreams? While walking? In the bath? He told me it's a gradual evolution, the result of having felt his way into the material. "First I have to face the soul of the tree," he says. This may last for days as he reckons with the tree's spirit and considers the shape, girth, heft, and condition of its wood. "At night I take a bath, have dinner, enjoy a glass of wine, and go to bed. And then one morning when I awake, the idea is there."

In the 1970s and 1980s Fujito produced small tabletop figures depicting the customs and ways of the Ainu. His models were relatives born before the first waves of Japanese settlers arrived in Hokkaido in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and he carved them in action -- 3D portraits, as it were, of bygone times. Some are performing ceremonial rites, others are walking, fishing, hunting with bow or rifle, tussling with bear cubs. These personal works were his means of honoring, through the Ainu tradition of woodcarving, their memory and shared culture.

|

|

It's hard to believe Kegani (Horsehair Crab; detail, 1995, Japanese yew) is carved of wood. |

In the late 1970s he began a new style focused on animals in the wild, typically in decisive moments like something off the pages of a nature magazine: an eagle grasps a bounding rabbit, an owl startles a mouse, a fox springs into a dash, a bear leaps from a tree. Each work and the stand on which it rests are, with few exceptions, carved from the same block of wood -- studies in cantilevered balance.

In 1950, the summer he would turn 16, Fujito went from his home in Asahikawa to the hot-spring resort of Lake Akan, where he worked carving bears outside a souvenir shop at the height of the tourist season. He returned each summer for another two years, drawn by the beauty of the area and the freedom of working on his own. When he was 18 he traveled farther afield to Honshu, working the department-store circuit doing live demonstrations at Hokkaido fairs in Tokyo, Osaka, Nagasaki, Kagoshima. In 1960 he returned to Lake Akan and his old job at the shop. By this time he could produce as many as five 15-centimeter bears a day. In 1963 he sold a relief carving to his employer for enough money to put a down payment on a place of his own. The following year he was running Kuma no Ya, still in business today.

|

|

Okami (Wolf; detail, 2002, ash bogwood). Fujito made his first wolf figures in the late 1970s using walnut wood, but it was works like this one, carved some three decades later of ash bogwood and much closer to the actual color of the Hokkaido wolf, that truly satisfied him. |

Another key animal for Fujito is the Hokkaido gray wolf. Revered by the Ainu for its hunting prowess, it was honored along with the bear and owl as a deity. His first encounter with one was at the age of 17. Not a live one, of course -- the animal had been eradicated much earlier after two decades of systematic bounty killing by Meiji-era settlers. (Fujito notes that the last trace of the species is a record of a few pelts traded in Hakodate in 1896.) Standing in front of a fusty old taxidermy mount in a university exhibit, he found himself in conversation with the animal. He exclaimed to his father that he wanted to try his hand at carving one. Far from being encouraged, he received a curt and abusive response. Though it would take him years to realize his wish, he never gave up his determination to tell the wolf's story.

|

|

Okami to shonen no monogatari (Tale of a Boy and Wolves) relates our lost and not-so-lost connections to the natural world. In this scene, a mother and father wolf rescue an Ainu baby swept away from his parents while they were fishing. |

In the late 1970s, Fujito produced his first wolf carvings -- figures in the wild, hunting deer and rabbits, moving in packs, raising cubs. But he says it wasn't until he was in his late sixties -- almost three decades later -- that he began to produce wolves he was really pleased with. "My father had long been gone. Still, it took me all those years to finally give myself permission. I had to take a hard, searching look at myself and the past."

As best I understand them, the words Yaykursapte! Kamuy utar in the Ainu translation of the exhibition's Japanese title refer to just such an uncovering process -- moving out from the shadows to reveal oneself, in full sacred connection with the natural world.

This vignette of Fujito's Okami to shonen no monogatari (Tale of a Boy and Wolves) recounts history plainly: those clearing Hokkaido's lands for ranching were paid for every pair of wolf ears they collected. The culling was done by rifle and with poisoned deer meat left in the woods. |

In Fujito's fable, the Ainu boy is raised by the wolves only to witness their eventual demise at the hands of humans, a world he chooses to denounce. At the age of 17, he sets off in the winter snow with his sister -- the last remaining wolf -- for kamuy mintar, the playground of the gods. The tale concludes, "Had he chosen to stay in this land and follow his ancestors' ways, he would have grown into a fine man indeed."

Following its run in Sapporo, the exhibition will travel to the National Museum of Ethnology in Osaka for two months, starting 11 January 2018.

All photos are by Susan Rogers Chikuba, with the permission of Takeki Fujito and Sapporo Art Museum.

|

|

|

Susan Rogers Chikuba

A Tokyo-based writer, editor and translator, Susan Rogers Chikuba has been following popular culture, design and art in Japan for three decades. She has edited works from bestseller crime mysteries to a film series on the country's Living National Treasures. In addition to developing communication tools for the hospitality and travel industries she covers little-known destinations and the people and lifestyles found there for domestic and international publications. |

|

|

|