|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese residents of Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Adventures in Sound: The Takehisa Kosugi Exhibition

Christopher Stephens |

|

Heterodyne II (2002/2017). |

Two electric fans stand face-to-face on a low pedestal, pivoting back and forth at different speeds, their shadows projected on the large curved wall behind them. Attached to the right side of each fan guard is a small speaker, which periodically emits a sputter, click or vocal muttering apparently plucked out of the ether and altered by the changing distance between the fans' heads and the whirring of their blades. This visually unassuming yet aurally compelling work, Heterodyne II, serves as the introduction to Ongaku no Pikunikku (Music Picnic), a collection of ten installations and a historical retrospective on the avant-garde musician and pioneering sound artist Takehisa Kosugi (b. 1938), currently underway at the Ashiya Museum of Art & History in Hyogo Prefecture.

Though his is not quite a household name, Kosugi's career and influence span six decades, and include a list of collaborators that reads like a who's who of 20th-century art. Trained in musicology at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music, Kosugi helped found Group Ongaku (with Yasunao Tone and Mieko Shiomi among others) in 1960. This was the first Japanese ensemble devoted to improvisational sound and actions. In his own right, Kosugi soon began working with the radical performance group Hi-Red Center and butoh dance originator Tatsumi Hijikata. In the mid-'60s, Kosugi's instructional pieces (based on written cues like "Roll up a long cord" and "Put out a hand from a window for [a] long time") caught the eye of Fluxus leader George Maciunas, who invited him to move to New York in 1965. There Kosugi became involved in the Annual Avant Garde Festival, established by the cellist and performance artist Charlotte Moorman, and developed a close alliance with Moorman and her frequent collaborator Nam June Paik, widely credited as the father of video art.

|

|

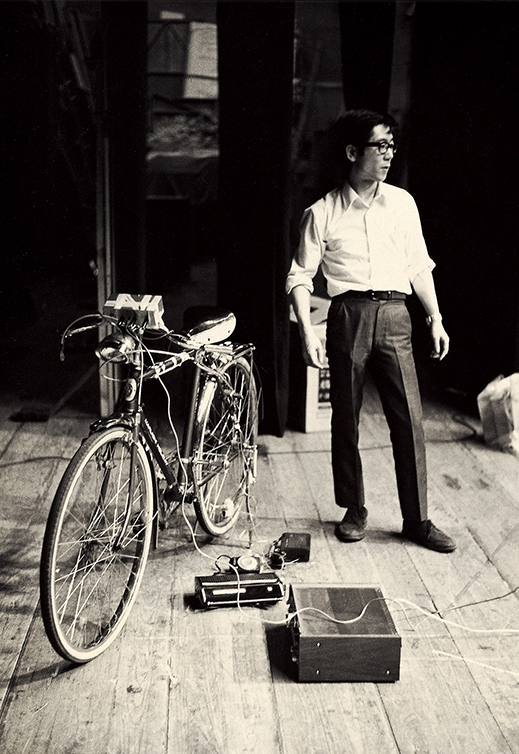

Kosugi performing Catch-Wave '68 (1968). |

Kosugi returned to Japan in 1967, and two years later formed an experimental music collective called the Taj Mahal Travellers. Featuring Kosugi on violin, his primary instrument since childhood, the group combined Eastern and Western, acoustic and electric instruments to hypnotic effect in sprawling improvisations punctuated by drones and pulses. After the Travellers went their separate ways, Kosugi moved back to the U.S., and in 1977 was invited to join the Merce Cunningham Dance Company as a resident musician/composer alongside David Tudor. Kosugi had worked with Cunningham and the company's music director, John Cage, when they first visited Japan together in 1964, and he remained with the group until it disbanded in 2011 (serving as music director for the last 15 years or so). It was also in the late '70s that Kosugi began making innovative sound installations, anticipating what later came to be known as "sound art."

Mano-dharma, electronic (1967/2017). |

Kosugi traces his interest in electronics to a crystal set he made in his teens. This simple mechanism, consisting of a coil, tuning capacitor, signal diode, and earphone, is directly powered by radio signals rather than a battery, enabling the user to capture a broadcast, albeit at a very low volume, via a simple wire antenna. Radio remains a central element in Kosugi's work, as seen in Mano-dharma, electronic. Several AM transmitters and receivers are suspended from the ceiling by strings, swaying gently in a breeze created by an electric fan, against a backdrop of silent ocean waves. The devices occasionally drift within range of each other, causing sudden bursts of static and reminding us again that the air is cluttered with invisible signals or waves, which only become audible through these chance encounters.

Interspersion for Light and Sound (2001). |

Rather than viewing his installations as finished products, Kosugi sees the listener as the last piece of the puzzle. Your arrival marks the start of a unique and unrepeatable performance, which varies according to where you stand, what you perceive, and how long you choose to remain. Take, for example, Interspersion for Light and Sound. Four trays filled with sugar are positioned next to the window on pedestals. It is immediately clear that each substance has a different grind, ranging from fine to extremely coarse. With the bright sunlight flooding the gallery, you could be forgiven for simply admiring the differences in texture and moving on to the next display, but closer attention reveals a muffled bleep or subtle flash of colored light buried beneath the surface. This signal sends you back and forth between the four containers, searching for other sights and sounds, and noticing how the quality of both is affected by the sugar's physical composition. This process of observation, discovery, and experimentation constitutes a performance, triggered by the work but ultimately conceived by the visitor.

|

|

That applies equally to Light Music II, a cluster of roughly 30 small electric circuits, powered by dry cells or solar panels and connected to speakers or contact microphones. Scattered across the top of a white table, the menagerie of devices intermittently releases a variety of burps, chirps, and buzzes, making it seem as if they might hop away at any moment if it weren't for the rounded sheet of chicken wire that confines them to the space.

The archival section of the exhibition, approximately 300 items, traces Kosugi's adventures through a wealth of materials, including his university graduation thesis (dealing with improvisational music), an Astro Boy record (he was part of the team that produced sound for the animated TV series), pictures of the Taj Mahal Travellers on a pilgrimage to the Indian mausoleum from which they derived their name, snapshots of the artist on a private trip to an Ainu village with Cage and Cunningham, recordings (including one made with Kosugi's spiritual heirs, Sonic Youth), and posters, programs, and clippings detailing a life spent all over the globe.

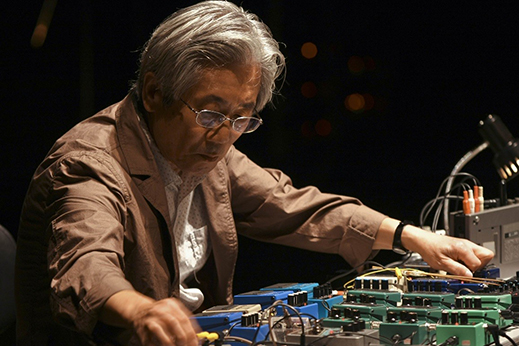

Takehisa Kosugi is one of those rare figures who has effortlessly defied genres, formed easy alliances with artists of diverse backgrounds, and paved the way for a new conception of sound and music.

|

|

Kosugi performing at the Yokohama Triennale in 2008. |

All photos by Kiyotoshi Takashima except Catch-Wave '68 (photographer unknown). All images provided by HEAR sound art library.

|

|

|

Christopher Stephens

Christopher Stephens has lived in the Kansai region for over 25 years. In addition to appearing in numerous catalogues for museums and art events throughout Japan, his translations on art and architecture have accompanied exhibitions in Spain, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, South Korea, and the U.S. His recent published work includes From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and Gutai: Splendid Playground (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2013). |

|

|

|