|

|

|

HOME > FOCUS > Timeless Emanations: The Supple Spontaneity of Bamboo, at Musée Tomo |

|

|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese residents of Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Timeless Emanations: The Supple Spontaneity of Bamboo, at Musée Tomo

Susan Rogers Chikuba |

|

Sustainable art: when Connection (2018) by Tanabe Chikuunsai IV is dismantled at the end of the Musée Tomo show, the bamboo will be recycled for future works. Left photo by Jeff Amas; right photo by Susan Rogers Chikuba |

Winding as it does through a seven-meter void that's papered in warm silver tones and fragments of poetry by Toko Shinoda, the spiral staircase leading to the theater-like basement galleries of Musée Tomo is, at any time, a provocative transitional space. All the more so at the present exhibition, where a massive floor-to-ceiling installation of woven bamboo writhes up through the well, its three hollow shafts twisting in organic dialogue with the steps. At its base the structure seems rooted to the wall and floor, a plant drawing nutrients from below and light from above.

The temporary piece is the creation of Chikuunsai IV, the only living artist of the seven introduced in Lines and Shapes, Lines and Spaces -- The Bamboowork of Iizuka Rokansai and Tanabe Chikuunsai, a gorgeous gambol through generations of works by the two elite lineages. The trio of intertwined trunks is his tribute to connections that link past, present, and future, as well as those between the museum and the two featured families.

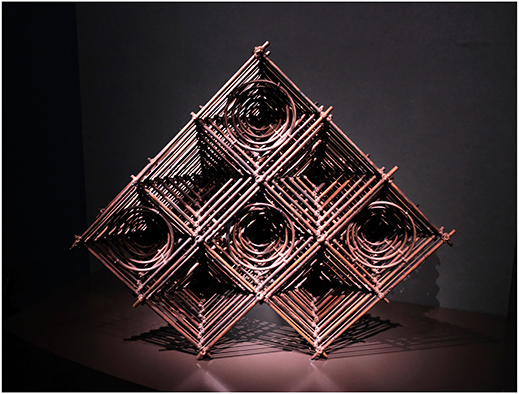

Mid- and late-Taisho era flower baskets by Iizuka Hosai II speak to the early-20th century shift among bamboo artists, from emulating traditional Chinese-style works to asserting their own creative independence. Photos by Jeff Amas |

The Iizukas, hailing originally from Tochigi, and the Tanabes, from Osaka, were central to the evolution of bamboo art in the Kanto and Kansai regions. As popular interest in the arts of ikebana and tea ceremony spread in Japan from the late 19th century onward, bamboo weavers shifted their focus from the intricate, finely plaited flower baskets of classical Chinese style to explore less formal modes of expression. With its presentation of works made from the 1910s onward, this exhibition captures the first fervent decades when, prompted by Taisho-era social reforms and the influx of ideas from art movements abroad, bamboo artisans began to experiment with abstraction and other forms of individual creativity.

|

|

|

|

|

The densely woven base of Yudachi (Evening Shower; early Showa) by Iizuka Rokansai sets off the vertical lines of the top section, where two rows of split and planed strips set inside and out are twisted to yield the textured effect of a sudden hard rain. Rokansai was one of the first bamboo artists to give poetic titles to his works. Photo by Jeff Amas |

Iizuka Hosai II (1872-1934) founded the Tokyo Bamboo Crafts Association and oversaw its activities at a time when basket makers were transitioning from traditional craft to personal art. His younger brother, Iizuka Rokansai (1890-1958), worked across the spectrum from the tight, minute plaiting of traditional weaving to freewheeling compositions made of bent or curved strips that showcased the inherent qualities of the material. One stunning piece on show through 3 June is fashioned from a single 170-centimeter stalk: Rokansai split its top half into strips, which he then bent back and wove onto the opposite, root end. He thus juxtaposed the inner and outer sides of the stalk to shape the basket proper, while using its round, intact lower half for the handle. His son Shokansai (1919-2004) spiced things up his own way, bringing his early training as a painter to framed wall panels of dyed bamboo set in geometric patterns. He later settled on utilitarian works that emphasized the plant's natural beauty. In 1982 he was designated a Living National Treasure, the second bamboo artist to receive this honor.

|

|

|

|

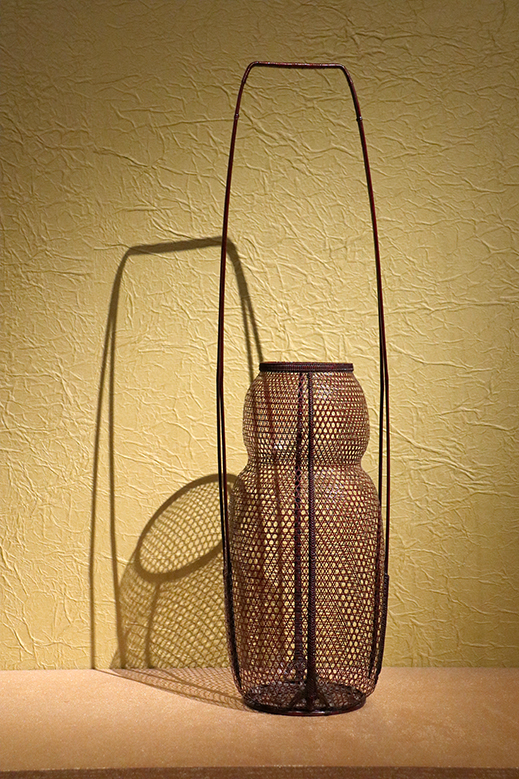

A gourd-shaped openwork (1940-1980) by Chikuunsai II, and the composition Mirai e no kanki (Delight for the Future; 2009) by Chikuunsai III, are prime examples of the respective styles of this father and son. Left photo by Susan Rogers Chikuba; right photo by Jeff Amas |

Chikuunsai I (1877-1937) settled in Sakai, Osaka -- a hallowed center of formal tea practice -- where he made a name for himself with densely woven Chinese-style basketry. His son, Chikuunsai II (1910-2000), specialized in light sukashi-ami openwork, using extremely fine strips less than a millimeter in width, while Chikuunsai III (1940-2014) in turn preferred modeling and built complex, unwoven abstract forms of unsplit bamboo. Chikuunsai IV (b. 1973), the youngest in the line, incorporates all of these approaches in his designs, creating works that are remarkable for their architectural quality.

Hyoretsu (Crevasse; early Heisei) by Iizuka Shokansai employs ara-ami coarse plaiting to weave strips of varied widths in seemingly random, but in fact carefully calculated, ways. Photo by Jeff Amas |

Curator Keiko Shimazaki points out that 33 years have passed since a large-scale exhibition focusing solely on bamboowork has been held in Tokyo -- the last being Modern Bamboo Craft in 1985 at the National Museum of Modern Art. "There are far more opportunities to view works of this caliber overseas than here in Japan," she adds, noting the fascination bamboo holds for art lovers beyond Asia. Last spring, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York brought together some 70 works in a show that drew 430,000 people; an exhibition at the Japan House in São Paulo last summer was seen by 190,000. This fall the Musée du quai Branly in Paris, a venue dedicated to non-European indigenous designs, is slated to display some 200 baskets and other items tracing the history of the art in Japan. Shimazaki is hopeful that shows like Musée Tomo's will prompt greater interest in bamboowork here in its homeland, where the craft dates back to prehistoric times.

|

|

With the precisely spaced lines of its top and a loosely plaited base, this circa-1936 flower basket by Iizuka Rokansai unites formal and free-style weaving techniques in counterpoint, the whole set on a tilted axis. Photo by Jeff Amas |

The items introduced here will switch out to new exhibits after 6 June. As all 120 of the pieces to be shown are held in private collections, the Musée Tomo show is a rare opportunity to appreciate diverse interpretations of this material in works of fine art.

Shimazaki will lead gallery tours (in Japanese) on 2 June and 7 July from 2 p.m. Also on the museum grounds is the Seiyokan, an early-20th century home and registered cultural property with a slate roof, teak paneling, and original Tiffany stained-glass windows. It will next open to the public on 23 June, when architect Yoshio Shinoda leads a tour at 11 a.m. followed by lunch at the museum restaurant (¥8,000 per person, reservations required).

Musée Tomo's garden is bursting in green right now. The museum restaurant overlooks it and is a fine place to stretch out your gallery visit with lunch or tea. Photo by Jeff Amas |

All images are by permission of Musée Tomo.

|

|

|

Susan Rogers Chikuba

Susan Rogers Chikuba, a Tokyo-based writer, editor and translator, has been following popular culture, architecture and design in Japan for three decades. She covers the country's travel, art, literary and culinary scenes for domestic and international publications.

. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|