|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese residents of Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

The Yasuhiro Ishimoto Photography Collection Finds a Home in Kochi

Alice Gordenker |

|

|

"East Indian Lotus" (1986-87). Gelatin silver print. © Kochi Prefecture, Ishimoto Yasuhiro Photo Center |

It's difficult to find a label that fits photographer Yasuhiro Ishimoto (1921-2012). Was he "Japanese" because he had Japanese parents and eventually chose to live in Japan as a Japanese citizen? Or was he "Japanese-American," given that he was born in the United States and indeed imprisoned during World War II in an internment camp for Japanese-Americans? Perhaps it's best to describe Ishimoto as a photographer with ties to both countries who carried important ideas back and forth across the ocean, in the process becoming a recognized and influential force in modern photography.

Ishimoto's work and contributions are now poised for greater study and acclaim -- particularly in Japan -- thanks to the upcoming 100th anniversary of his birth, and the establishment of the Ishimoto Yasuhiro Photo Center at the Museum of Art, Kochi. Before his death in 2012, Ishimoto donated his personal archive of over 7,000 prints to this regional museum in western Japan, making it the largest and most important repository of his work anywhere in the world. It was perhaps an unlikely choice, given the museum's relatively remote location and the fact that its main claim to fame, to that point, was its substantial collection of paintings and prints by Russian-born painter Marc Chagall. Certainly, larger and better-known museums would have been happy to receive Ishimoto's gift. But Ishimoto favored Kochi because he had spent most of his childhood in the area, and because the museum honored him with a major retrospective in 2001.

|

|

|

The Museum of Art, Kochi. The building was designed to resemble the traditional storehouses of the region and is finished with the local variety of shikkui plaster. The museum holds the largest Chagall collection in Japan. |

Ishimoto was born in San Francisco to Japanese parents who immigrated to the U.S. to work as farmers. When he was three years old, the family returned to Japan to his parents' home ground in Kochi Prefecture, where he lived through high school. Japan was at war when he graduated, and his mother -- fearing he'd be drafted into the Japanese military -- urged him to leave the country. He returned to California alone in 1939, only to be rounded up the following year with other U.S. citizens of Japanese heritage and sent to an internment camp in Colorado. It was there that he began to learn photography, taught by fellow detainees.

|

|

|

|

|

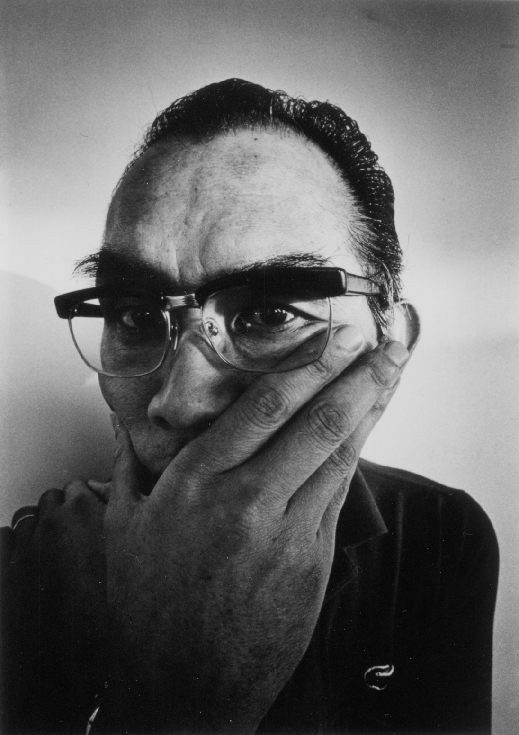

Self-portrait, Yasuhiro Ishimoto (1975). Gelatin silver print. © Kochi Prefecture, Ishimoto Yasuhiro Photo Center

|

Released in 1944, Ishimoto went to Chicago, where he initially studied architecture at Northwestern University but changed direction after meeting photographer Harry K. Shigeta. Ishimoto then enrolled in the photography program at the New Bauhaus/Institute of Design, where he studied under Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind, and soon made a name for himself, particularly for his street scenes of Chicago. Some of his early work was included in the Family of Man exhibition, curated by Edward Steichen, which toured the world in the 1950s.

A famous image from Ishimoto's Chicago, Chicago series: "Chicago, Town" (1959-61). Gelatin silver print. © Kochi Prefecture, Ishimoto Yasuhiro Photo Center |

In 1953 Ishimoto returned to Japan, and at the request of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, photographed the Katsura Imperial Villa in Kyoto. Built in phases between 1620 and 1658, the villa is a beautiful and understated building that epitomizes traditional Japanese architecture, and still inspires architects and designers around the world. Ishimoto eschewed the formal, documentary approach taken previously by the few Japanese photographers permitted to work on this august subject. Instead, he examined it as a painter might, focusing on texture, line and space, producing a stunning series of black-and-white images that are closer to abstract art than the typical architectural photography. The photographs were well received in the United States (and published as a book in 1960), but in Japan they caused something of a sensation. Ishimoto was awarded a major photography prize for the photos, in 1957, and praised for having injected new and exciting ideas from abroad into photography in Japan.

|

|

"Katsura Imperial Villa," Kyoto (1953-54). Gelatin silver print. © Kochi Prefecture, Ishimoto Yasuhiro Photo Center |

Ishimoto returned to Japan permanently in 1961, and in 1969 became a naturalized Japanese citizen. He earned his living largely through product and architectural photography, working regularly for such prominent architects as Kenzo Tange, Arata Isozaki and Hiroshi Naito. He also participated in numerous exhibitions and published more than a dozen books. His photographs were often featured on the cover of magazines, and he received many awards. In 1996, the Japanese government named Ishimoto a "Person of Cultural Merit" (bunka korosha), a high honor that comes with a lifelong stipend.

The Museum of Art, Kochi now has a dedicated gallery for Ishimoto's work in which it displays three exhibitions a year on various themes. The shows are sometimes organized around one of Ishimoto's most famous series, but the museum also strives to advance research and understanding by introducing lesser known themes and prints that may never have been previously published or exhibited.

Currently, the museum is featuring prints from Ishimoto's HANA (Flower) series. To create these large-scale studies of flowers in various stages, from first bud to wilting and decay, Ishimoto set up a makeshift studio in his apartment in Tokyo's Shinagawa district. He would position a bloom before the camera and wait for his moment, often rising from a meal to capture a specific point in the flower's life cycle. The HANA series was inspired by Irving Penn's Flowers collection, which the American photographer famously began in 1967 for Vogue magazine. But unlike Penn's images, which are in vivid color, Ishimoto chose to work in black and white. "I intentionally avoided colors," Ishimoto wrote in the foreword to the book HANA, published in 1988. "The first reason was, of course, that I hoped to take photographs that scrupulously adhered to the flower's form; but looking back, I can also see that I was resisting the usual mundane inundation of color, which seemed to me like nothing less than insanity."

|

|

"Common Cosmos" and (right) "Yukimochi-so, a kind of Arisaema" (both 1986-87). Gelatin silver prints.

© Kochi Prefecture, Ishimoto Yasuhiro Photo Center |

In preparation for 2021, which will mark the centenary of Ishimoto's birth, museum staff are cataloging and digitizing their collection of the photographer's work, which currently includes some 100,000 negatives, 55,000 positive films, and 35,000 prints. The goal is to have the prints online and available to the public by 2021, when the museum will hold a particularly large special exhibition. But even though the facility is the world's largest repository of Ishimoto's work, there are holes in its collection. "We hold many negatives for which we do not have a corresponding print, although we believe prints were made and may still exist somewhere," explains curator Keigo Amano. "They may be forgotten in a file cabinet in the offices of an architect or magazine, and we would very much like to bring such treasures into the museum where they can be properly conserved, studied, and added to the record of his oeuvre. Part of our work in building the archive includes outreach to offices, individuals and organizations that may have once worked with Ishimoto, including those both in Japan and abroad."

If you do visit Kochi, and especially if flowers are on the agenda, a stop at the Kochi Prefectural Makino Botanical Garden is highly recommended. The six hectares of gardens and greenhouses, located on a picturesque mountainside just outside of town, honor Tomitaro Makino (1862-1957), said to be the father of botany in Japan. The gardens are a lovely complement to Ishimoto's beautiful and thoughtful studies of flowers.

All images courtesy of The Museum of Art, Kochi. Copyright held by Kochi Prefecture, Ishimoto Yasuhiro Photo Center. |

|

| HANA |

7 August - 25 November 2018

There will be a change of exhibits on 8 October.

|

|

|

| The Museum of Art, Kochi |

353-2 Takasu, Kochi, Kochi Prefecture

Phone: 088-866-8000

Hours: 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Closed on Mondays except when Monday falls on a national holiday (in which case the museum is closed the following day) and 27 December - 1 January.

Access: The closest airport is Kochi Ryoma Airport, which is served by daily flights from Tokyo's Haneda Airport, Osaka's Itami Airport, Nagoya and Fukuoka. The museum is about a 20-minute taxi ride from the airport, or you can take the airport "Renraku" (connector) bus to the Kazurajima bus stop and walk about 16 minutes to the museum. From the castle area in the city center, catch the Tosaden streetcar at Kochijo-mae station and ride to Kenritsu Bijutsukan-dori station. From there, it's a 6-minute walk to the museum.

|

|

|

|

Alice Gordenker

Alice Gordenker is a writer and translator based in Tokyo, where she has lived for more than 19 years. For over a decade, she penned the "So, What the Heck Is That?" column for The Japan Times, providing in-depth reports on everything from industrial safety to traditional talismans. She translates and consults for museums, and has a special interest in making Japanese museums more accessible for visitors from other countries. |

|

|

|