|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese residents of Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Affinities in Art: Marcel Duchamp and Japan

J.M. Hammond |

|

The turn taken by 20th-century European modern art away from the established principles of the western tradition can reveal some surprising correspondences with other, quite different, art practices, including those of Japan.

So far, such investigations concerning Japan have centered on western art that has consciously adopted aspects of a Japanese visual sense -- Vincent Van Gogh, Matisse, the Japonisme movement, and so on. Now an exhibition at the Tokyo National Museum is focusing on the French-American artist Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968). Collaborative Exhibition Project between the Tokyo National Museum and the Philadelphia Museum of Art: Marcel Duchamp and Japanese Art attempts to provide a thorough overview of his career, and to investigate similarities between his ideas and Japanese art practices -- similarities that Duchamp was most likely not even aware of himself.

The long arc of Duchamp's career is meticulously documented in Part 1, "The Essential Duchamp, Commemorating the 50th Anniversary of Marcel Duchamp's Death." This formidable task is no doubt made somewhat easier as -- despite the fact that the originals of some of his earlier works have disappeared -- Duchamp was a keen archivist of his own art pieces, working processes and ideas, especially as his career progressed.

The exhibition features sketches, paintings, photographs, short films, installations, publications, and various boxed series of notes and documents. Most of the famous Duchamp artworks are here, including a replica of his enigmatic The Large Glass. There are also many photographs of the artist posing with his various creations.

|

|

|

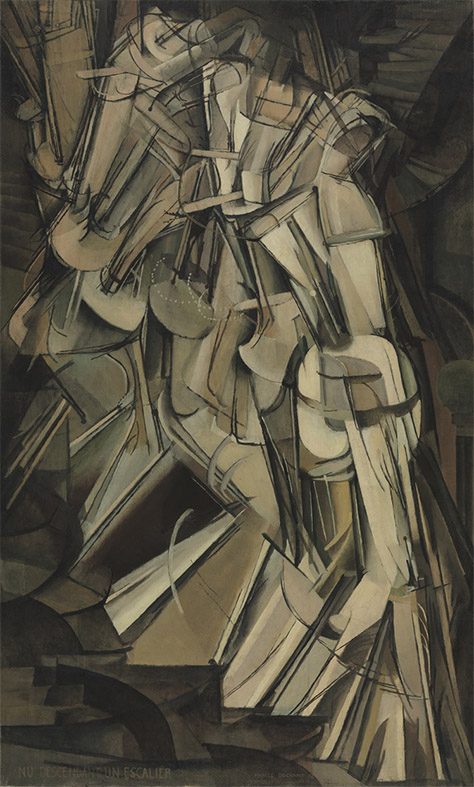

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), 1912, Philadelphia Museum of Art. The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, 1950. © Association Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris & JASPAR, Tokyo, 2018 G1350 |

Portrait of Dr. Dumouchel is an interesting early painting from 1910 that reveals the artist's interest in portraying phenomena beyond the visual realm. A mysterious aura can be seen around the hand of Duchamp's childhood friend, which may allude to the doctor's work with X-ray technology, and/or suggest a special healing power. Various paintings on display represent Duchamp's early experimentation with cubism, and lead to his break from the style with his classic Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) of 1912, in which the human form is painted in successive stages of motion.

The most important aspect of Duchamp's thinking and artistic practice as applied to Japanese art is his contention that the hand of the artist in the physical production of an artwork is unnecessary, and, by extension, his rejection of the concept of the originality of the artist -- an ideal highly valued in the western tradition. Central to these ideas is his concept of the "readymade" -- industrially made objects that Duchamp found or purchased, provided a new idea for, and displayed as his own art. Included here is Bottle Rack from 1914, a typical circular rack used for drying out large numbers of bottles. It is suspected that even though Duchamp professed to have no interest in the aesthetic quality of his readymades, he may have been attracted by the rack's threatening spikey protuberances and their sexual connotations. It is considered Duchamp's first "true readymade" as he presented it just as he found it. In contrast, Duchamp also produced what he called "assisted readymades" because of the intervention of the artist -- such as with Bicycle Wheel, from the year before Bottle Rack, when he mounted a bicycle wheel on top of a stool so it could be spun around freely.

Duchamp also changed the viewer's perception of objects that were chosen as readymades through the playful application of a title that negated the original intention of the object (like the bicycle wheel that could no longer be used as such, once it was mounted on a stool) or provided it with a new idea, such as the replica of the men's urinal he exhibited in 1917 under the title Fountain. What originally took in liquid is now transformed, in the mind's eye, into an object that potentially releases it. Signed with the pseudonym R. Mutt, Duchamp also adds another layer of characteristic, and often crude, punning.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Marcel Duchamp, Bicycle Wheel, 1913/1964, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of Galleria Schwarz, 1964. © Association Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris & JASPAR, Tokyo, 2018 G1413

|

|

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917/1950, Philadelphia Museum of Art. 125th anniversary acquisition; gift (by exchange) of Mrs. Herbert Cameron Morris, 1998. © Association Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris & JASPAR, Tokyo, 2018 G1311 |

The second, and less extensive, part of the exhibition, "Rediscovering Japan through Duchamp," attempts to take some of Duchamp's ideas -- what were considered radical innovations in Europe -- and view them in the context of certain aspects of Japanese art. For example, the exhibition suggests that the emphasis on originality in the European art tradition that Duchamp rallied against was rare in Japan anyway, as artists worked on established themes commissioned by their patrons. This may be so, but it overlooks the fact that any "originality" a European artist enjoyed, was, for many centuries, also bound by similar constraints.

Even so, the exhibition suggests that Japanese artists nonetheless managed to infuse their work on accepted themes with their own innovations and originality, and presents two works on the same theme for consideration. The 15th-century Shoulao under a Plum Tree, attributed to Sesshu Toyo, portrays the Chinese god of longevity and is dense with details and symbolism. Hashimoto Gaho's Meiji-era (1868-1912) portrait of Shoulao owes much of its composition to Sesshu, but offers a starker, simplified version that makes full use of empty white space and bold black ink lines. It remains unclear not only how this relates to Duchamp's views on originality, but also how this process of adapting and changing is different in nature from, to give just one example, Pablo Picasso's radical reimagining of the work of Velasquez, El Greco, Ingres or others.

The exhibition compares Duchamp's aforementioned Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) with a work from 13th-century Japan; both attempt to depict action from various points in time in one image. The main figure in Narrative Picture Scroll of the Chronicle of the Heiji Civil War is depicted in various stages of the story as it unfolds -- panicking at the news of his foe's escape from imprisonment, turning around and then thrusting himself through a bamboo curtain. Duchamp's study of motion resembles a series of rapidly taken photographs, or frames of a movie strip, closely superimposed over each other to suggest a brief continuum in time, whereas the action in the scroll is presented more as discrete moments separated in both time and space. Both offer an alternative to the traditional European conception of a painting as a static window on the world, a kind of snapshot of an event frozen in time.

|

|

Tea Bowl, known as "Mukashibanashi," Studio of Chojiro; Raku ware, Kuroraku type, Azuchi-Momoyama period, 16th century. Tokyo National Museum |

Most convincing, perhaps, is the suggestion that something like Duchamp's readymades had already appeared hundreds of years earlier in Japan. Tea master Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591) turned upside down the prevailing taste for ornate, decorative vessels by seeking out simpler and seemingly unrefined pieces, or adapting objects from nature. A small black tea bowl displayed here would no doubt have been considered a humble piece of pottery before it attracted the eye of Rikyu, who valued it for its rustic simplicity and used it in formal tea ceremonies. In the exhibition it is dimly lit from above only, perhaps in an attempt to recreate how it would appear half-obscured in the dim light of a tea room.

Also on display here is a vase that Rikyu is said to have "made" himself by cutting a length of bamboo, altering it slightly, and giving it a new conception and function, just as Duchamp was later to do in the different context of mass-produced industrial objects. However, there are some differences. Rikyu used and promoted the objects he found, whereas Duchamp gave his readymades the status of artworks -- and his own artworks at that. Also, the tea master was essentially expanding the possibilities of what was considered good aesthetic taste, whereas Duchamp professed to be against the very idea of good taste.

So while the exhibition points out various correspondences between aspects of Japanese art and Duchamp's innovations, it feels like the actual positions of art in Japan and in the Western tradition Duchamp was rebelling against need to be more clearly situated in order to make such comparisons truly meaningful. Given the complexity of the topic, at times the valuable insights offered here pose as many new questions as they answer, but the exhibition suggests some intriguing affinities between the art of Japan and an artist who still manages to perplex people to this day.

|

|

Flower Vase with Side Opening, known as "Onjoji," attributed to Sen no Rikyu,

Azuchi-Momoyama period, 1590. Gift of Naoki Matsudaira. Tokyo National Museum

|

All images courtesy of the Tokyo National Museum. |

|

|

J.M. Hammond

J.M. Hammond researches modernity in Japanese art, photography and cinema, and teaches in Tokyo, including as a faculty lecturer in the English department at Meiji Gakuin University and at Gakushuin University. He has written about art for The Japan Times for over a decade. His essays include "A Sensitivity to Things: Mono No Aware in Late Spring and Equinox Flower" in Ozu International: Essays on the Global Influences of a Japanese Auteur (Bloomsbury, 2015) and "The Collapse of Memory: Tracing Reflexivity in the Work of Daido Moriyama" for The Reflexive Photographer (Museums Etc, 2013) [reprinted in the same publisher's 10 Must Reads: Contemporary Photography (2016)]. He has given various conference papers, including at the University of Hong Kong and the University of Oxford. |

|

|

|