|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese residents of Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Art Takes a Bath: Dogo Onsenart 2018

Colin Smith |

|

|

Mika Ninagawa's installation at the historic Dogo Onsen Honkan (now ended). © Dogo Onsenart 2018 |

Since 2000 the number of annual, biennial and triennial art festivals in regional cities and rural areas of Japan has steadily grown, and contemporary art has joined local specialty foods and yurukyara mascot characters as a means of drawing attention and boosting tourist traffic to places off the beaten path. The Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale, first held in 2000 in the mountains of southern Niigata Prefecture, is a trailblazer among such events, created to "reveal existing assets of the region using art as a catalyst, rediscover their values, communicate these to the world and find a way to revitalize the region … Community building through art has drawn attention as the Tsumari Approach" (Echigo-Tsumari Art Field website).

Yet publicly funded art events have sometimes been divisive, going back to Expo '70 Osaka when iconoclastic avant-garde artists were criticized for getting on board with a triumphal national spectacle. It's been observed that the "community building" model obliges artists to please organizers (for example, by producing works related to community history or local industry that can feel like school assignments), overemphasizes art-as-entertainment with a superficial carnival atmosphere, and creates an unsustainable bubble. However, the events undeniably help artists reach a vast swath of the usually non-art-viewing public, bring people into contact with new ideas, and when successful, achieve the goal of enlivening moribund areas and stimulating local economies. The 1991 collapse of Japan's economic bubble, a plunge in corporate arts funding, a wave of municipal mergers creating new communities in search of identities and branding, and the decline of public works projects keeping rural areas afloat all fertilized the soil for regional art festivals as a means of attracting attention, investment and visitors. Major festivals today include the Setouchi Triennale, Yokohama Triennale, and Aichi Triennale, and smaller ones are springing up all the time.

|

|

|

Chie Matsui, Seiren-maru, nishi e (The Ship Seiren-maru Sails West), at the Sachiya Hotel. © Dogo Onsenart 2018 |

Dogo Onsenart was first held in 2014, and the current (fourth) edition is the largest yet. It's certainly one of the longest-running art festivals at 18 months, from September 2017 until the end of February 2019. Dogo Onsen, in Matsuyama, Ehime Prefecture, is one of Japan's "three ancient hot springs," mentioned in the 8th-century Man'yoshu and, legend has it, bathed in by such luminaries as Prince Shotoku (574-622), an injured white heron that recovered and flew once more (now a local symbol), and the deathly-ill deity Sukunahikona no Mikoto, who also recovered and danced joyfully atop a stone. Today there are various places to bathe, but the main draw is the splendid Dogo Onsen Honkan (main building), built in 1894, one inspiration for the bathhouse in the Ghibli animated film Spirited Away, and famously a refuge for Natsume Soseki during his stint teaching in Matsuyama, as it was for the narrator of his novel Botchan. Today you can bathe there in the "Water of the Gods," lounge in a yukata robe and sip tea.

|

|

Aquirax Uno, Ren-ai Jiten (Encyclopedia of Love), room installation at the Old England Dogo Yamanote Hotel. © Dogo Onsenart 2018 |

The photographer and film director Mika Ninagawa, one of the biggest names at Dogo Onsenart 2018, filled the Honkan with an installation (now ended) of large images of fireworks in her signature vivid hues. Another well-known participant is Osaka-based multimedia artist Chie Matsui, whose installation features elaborate, soft and airy narrative paintings of a fairytale voyage from Osaka to Dogo. Veteran illustrator and graphic designer Aquirax Uno is about the same age as graphic designer and painter Tadanori Yokoo, and they both made posters for Shuji Terayama and his experimental theater troupe Tenjo Sajiki in the 1960s and 1970s. While they and other contemporaries share a Pop sensibility and an updated take on the early 20th-century ero-guro-nansensu (erotic, grotesque, nonsensical) aesthetic, Uno's recent illustrations evoke the "Gothic Lolita" subculture and have an enthusiastic female following. Here he's done a whole hotel room, which you can occupy for 15 minutes (¥1,000) during the day.

|

|

|

|

|

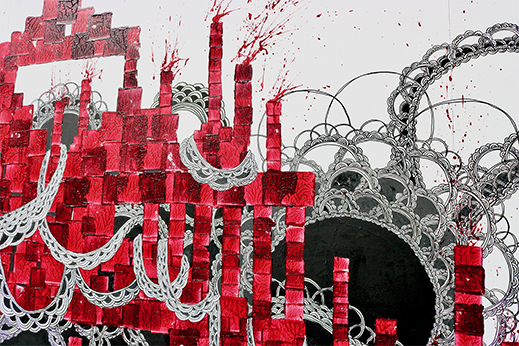

Naho Ishii, Body of City, created in a live public painting event in November 2018 on a corner near Dogo Onsen Station. Photos by Tomomi Saeki, © Dogo Onsenart 2018 |

The youngest participant, Naho Ishii (b. 1991), first showed at a gallery run by Takashi Murakami in 2010. Her works combine architecture that proliferates like cells -- recalling the mammoth housing project on an artificial island in Tokyo Bay where she grew up -- and such motifs as ornate girlish hairstyles and deer antlers. She does public paintings using red block stamps to create cityscapes of what look like bloody, veined cubes, to which she adds fine black-and-white networks and swirling lines. The product of her performance in Dogo is behind the free open-air footbath near the historic station, reached from downtown Matsuyama by tram or the Botchan Train, a picturesque diesel replica of the minuscule steam-powered train Soseki (and Botchan) rode.

|

Naho Ishii at work on Body of City. |

Ishii's project is titled "Let's Create Fusion!" and this aptly expresses the impetus for small-scale art festivals like Dogo Onsenart. While there may not be enough works distributed around the streets, shopping arcades, and buildings to make Dogo an art destination in its own right, onsen enthusiasts will want to visit the venerable hot springs anyway. And if they appreciate the art, that makes Dogo stand out among Japan's many hot spring resorts with their inns and hotels, tasty local cuisine, and people walking around in yukata.

The "Tsumari Approach" is largely the vision of Fram Kitagawa, long-serving director of the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale and the Setouchi Art Triennale, who has spoken of "bringing energy back to the region(s)" and transcending the "urban focus of 20th century art" by placing contemporary art and architecture in natural or rural surroundings. It seems this approach can be scaled to single city neighborhoods as well as to sprawling natural environments, and in the case of Dogo Onsenart it makes for a memorable trip. After a soak, the legends about miraculous healing properties seem pretty believable. On 15 January 2019 a several-year renovation of the Honkan will begin, and various sections, in turn, will be closed or covered with sheeting. Now's the time to visit.

|

|

The Botchan Train is one way to reach Dogo Onsen. Or take a bright orange tram, celebrating the area's prized citrus fruits. Photo by Tomomi Saeki |

All images courtesy of Dogo Onsenart 2018. |

|

Dogo Onsen and environs

Information Desk: 6-8 Dogo Yunomachi, Matsuyama, Ehime Prefecture

Phone: 089-907-5930

Access: Dogo Onsen Station via the Iyotetsu tram from Iyotetsu Matsuyama Station or the Botchan Train from JR Matsuyama Station

|

|

|

|

Colin Smith

Colin Smith is a translator and writer and a long-term resident of Osaka. His published writing includes the travel guide Getting Around Kyoto and Nara (Tuttle, 2015), and his translations, primarily on Japanese art, have appeared in From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and many museum and gallery publications in Japan. |

|

|

|