|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese residents of Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

City Upon a Hill: Hiroshima MOCA Shines On

Colin Smith |

|

|

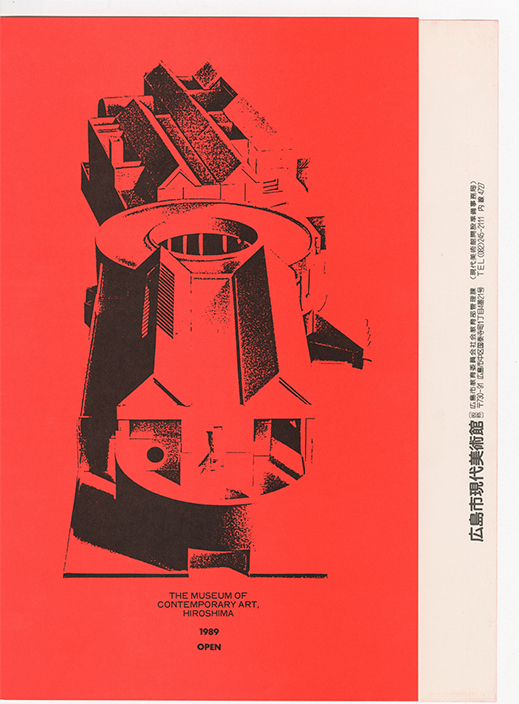

Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art when it opened in 1989 |

After a nice 500-meter walk up a winding road through Hijiyama Park from the tram station, you encounter the first section, "The Viewer: Expressions Rooted in Participation," of 30th Anniversary Exhibition: The Seven Lamps of the Art Museum, which runs through 26 May at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art. These works are interactive, or were made with visitor participation. Lie down on Taisuke Abe's soft, undulating quilted rendition of a Taro Okamoto painting (this might be good on the way out after touring the large, rich show, which takes at least two hours to view properly), and return to the womb by crawling inside Yoshio Kitayama's biomorphic bamboo and translucent pigskin construction Who Began to Write Hiroshima in Katakana Characters. These are in the bright, spacious circular lobby, its curve broken in one place indicating the direction of the atomic blast's epicenter. Looking out from here, the view of the trees and city below is anchored by Henry Moore's Arch, a monumental but warmly organic sculpture that seems to echo the form of the cenotaph honoring the bombing victims in Hiroshima's Peace Memorial Park.

|

|

|

Yoshio Kitayama, Who Began to Write Hiroshima in Katakana Characters, 1996 |

Thirty years ago, Hiroshima MOCA opened as Japan's first public museum devoted to contemporary art. This was a courageous move, especially for a city that isn't Tokyo, and thanks to it, Hiroshima has one of the finest museums of its kind in Japan. The current exhibition looks at the institution's past, present and future from many angles. Its title references The Seven Lamps of Architecture, an 1849 essay by the British critic and theorist John Ruskin, and while the structure of the seven-part show may not relate directly to Ruskin's lamps (a metaphor for architecture's various roles), the title points to the crucial, complex mission of museums and of this one in particular.

|

Stairs Monument by Bukichi Inoue, 1988 |

Museum architecture and outdoor sculpture are the focus of the second section. The striking Hiroshima MOCA building -- designed by Kisho Kurokawa, one of Japan's leading architects -- always makes its presence felt, and navigating its curves and spiral staircases is a refreshing departure from the boxy claustrophobia of some art venues. The museum was to be part of a much more extensive project, Hijiyama Arts Park, but in the end only it and the Hiroshima City Manga Library were built, resulting in a space surrounded by nature in a way few urban museums are.

According to curator Takeshi Matsuoka, who was in charge of organizing this exhibition, "One of our goals was to avoid simply showing how proud we are of our achievements, which you sometimes see with anniversary exhibitions like this one. We also wanted to convey some of the challenges we've faced, and things we want to improve going forward, as we prepare for major renovations" (scheduled to begin in 2020 and last until sometime in 2022).

|

|

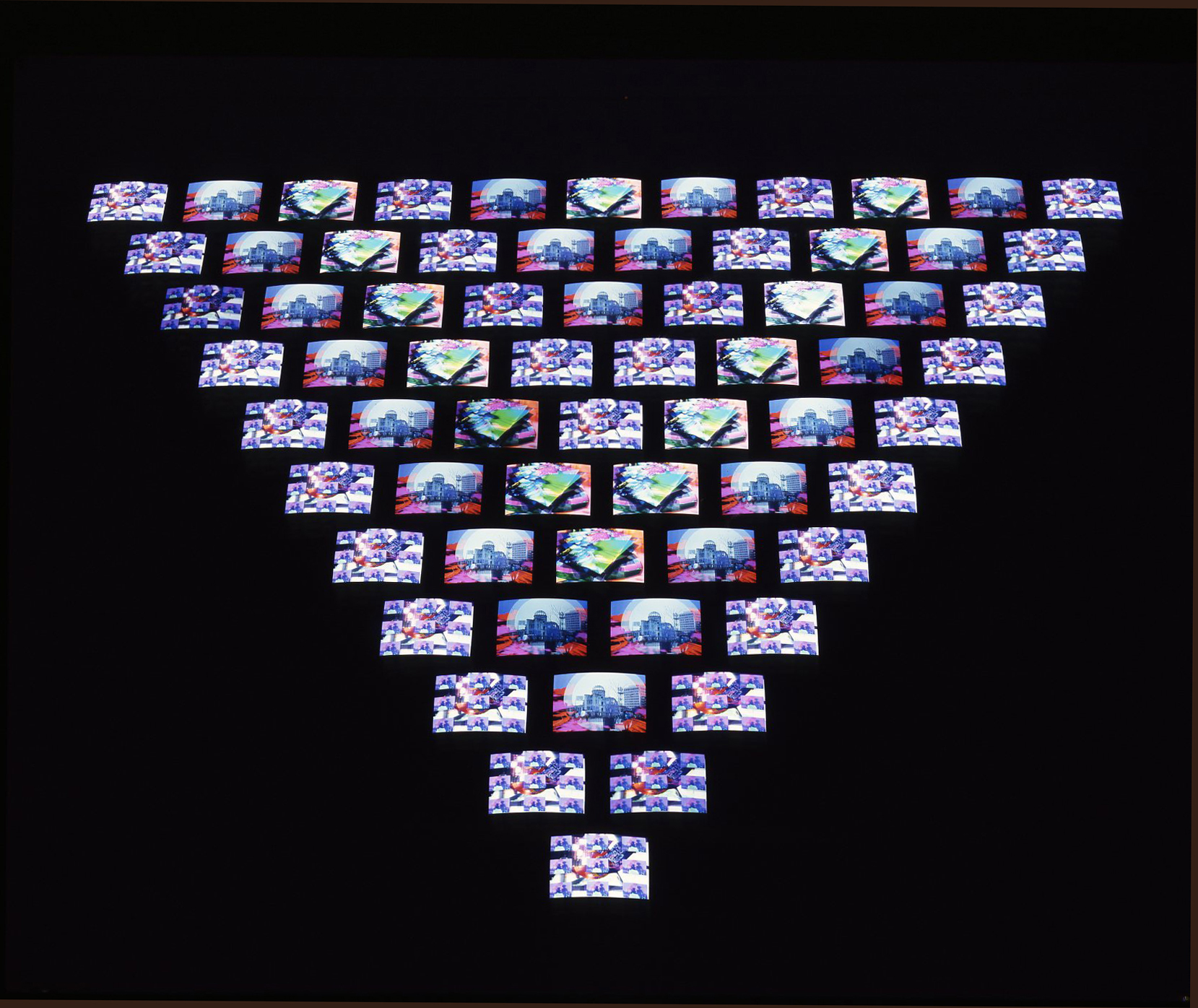

Nam June Paik, Hiroshima Matrix, 1988 |

Among these challenges are the maintenance of the building and its collection, a process showcased in an intriguing look behind the scenes in Section 4, "Leaving Something Behind: The Current State of Restoration and Conservation." There is a re-creation of a conservator's work area, where on some days visitors can watch the work being carried out, and a video showing extensive restorations being done on Toshi and Iri Maruki's Hiroshima Panels, one of which is on view. All art is subject to the ravages of time, but contemporary art in particular can be intentionally impermanent, or may incorporate disposable everyday objects or technology that becomes obsolete. A large, hallucinatory installation by video art pioneer Nam June Paik makes one wonder: what happens when those iconic cathode-ray-tube TVs burn out, and no manufacturers are producing new ones? His work wouldn't look the same on flat-screen digital displays. Another installation, everything is everything by Koki Tanaka, consists of videos of actions performed with colorful mass-produced objects, and similar objects scattered around, but their arrangement is variable and they will need replacement. A generic, off-the-shelf quality is essential, and requires that they be newish.

|

|

Koki Tanaka, everything is everything, 2005-06

|

Curator Matsuoka notes that Hiroshima was perhaps more open than some cities to the idea of a public contemporary art museum because of new art's power to address the Hiroshima bombing and the quest for world peace. The Hiroshima Art Prize, awarded every three years, recognizes art that contributes to this quest. A gallery with works by most of the 11 winners thus far (all prominent international artists, mostly non-Japanese) is one highlight of the show, featured in Section 3, "Here, Hiroshima and HIROSHIMA." The all-caps rendering represents the English equivalent of "writing Hiroshima in katakana characters" per the title of Yoshio Kitayama's aforementioned work, a practice that identifies Hiroshima not as a city, but as an idea and a universally known historical event.

Kitayama has another fascinating installation elsewhere in the show, the product of workshops he conducts. He has been drawn to themes of life and death since childhood, and has for decades been clipping out death-related newspaper articles (never in short supply), making drawings based on them and holding workshops where participants do the same. Huge masses of these are hung on curving corridor walls. The theme is grim, and the juxtaposition of headlines like "Mortar and Pestle Prepared in Advance to Grind Corpses" -- some recent and some yellowed, their impact softened by time -- with often absurd, darkly hilarious drawings by members of the public could be seen as irreverent. However, it has the effect of humanizing and putting faces on, for example, "Three More Dead in Group Suicide, Met Online" while showing how we use humor to deal with the unthinkable.

The works in Section 7, "In Between, Openings, Etc.: Works That Make Use of Gaps in the Museum," appear in unexpected places throughout the venue, illustrating the museum's commitment to thinking outside the box and making the best use of its wonderful building. Thirty years on, Japan's first public museum of contemporary art continues to evolve, and this show offers not only highlights of its excellent collection, but also a fascinating glimpse backstage at what keeps it going.

|

|

Flyer announcing the opening of the museum, 1989

|

All images courtesy of the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art.

|

|

|

Colin Smith

Colin Smith is a translator and writer and a long-term resident of Osaka. His published writing includes the travel guide Getting Around Kyoto and Nara (Tuttle, 2015), and his translations, primarily on Japanese art, have appeared in From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and many museum and gallery publications in Japan. |

|

|

|