|

|

|

HOME > FOCUS > The Peddlers, Porters, Pawnbrokers and More: Hokusai's People at Work |

|

|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese residents of Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Peddlers, Porters, Pawnbrokers and More: Hokusai's People at Work

Susan Rogers Chikuba |

|

|

The angular cuts and reflective surfaces of Kazuyo Sejima's design for the Sumida Hokusai Museum echo the precise yet warm and inquisitive gaze of Katsushika Hokusai, Edo's master chronicler. (Left photo © Forward Stroke; right photo by Susan Rogers Chikuba) |

Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) lived most of his 90 years in what is now Tokyo's Sumida ward. Not far from Ryogoku Station, just off the street on which he was born, the Sumida Hokusai Museum opened in 2016 to showcase the legacy of this neighborhood's most acclaimed native son. Its present exhibition, Edo Livelihoods by Hokusai, reveals the artist's sharp and often playful eye as he captured people at work.

Poem by Fujiwara no Michinobu from the series One Hundred Poems Explained by a Nurse, c. 1835. To illustrate a romantic 10th-century verse in which a lover laments the too-soon arrival of dawn, Hokusai offers, in true Edo style, palanquin bearers departing the Yoshiwara brothels at sunrise. |

Hokusai is renowned for his ukiyo-e prints of beautiful women and fabled landscapes, but this exhibition draws largely from his prolific career as an illustrator. Those who fancy antiquarian books will be pleased to know that there are dozens on display, their pages opened to his meticulous drawings. Woodblock prints and paintings are among the 102 works, too, but don't expect lots of bold splashes of color -- the delights of this show take time to absorb.

A New Tale of Kasane's Liberation, Kyokutei Bakin (author), Katsushika Hokusai (illustrator), 1807. On the fifth day of the fifth lunisolar month, families with sons used to display dolls and marionettes symbolizing strength and fighting spirit. Suspended from a vendor's umbrella, they would bob and jounce as he moved along. |

The exhibits are organized in six sections -- selling, harvesting, entertaining, hauling, making things, and otherwise providing services. Pore over them carefully and you'll be rewarded with finely rendered scenes that pulse with life as it was in Japan two centuries ago: peddlers of bear balm and chili powder in bustling streets, fishermen repairing nets, storytellers engaging a crowd, packhorse drivers assisting travelers, candymakers sculpting birds, a samurai having his topknot combed. Hokusai's sketching skills are a treasury of customs and trends of the times, from hairstyles to what class of person used what kind of umbrella.

Peepshow Box, 1794-97. Note Hokusai's use of perspective in the stereoscope sign, suggesting the illusion of depth offered within. |

|

|

|

|

|

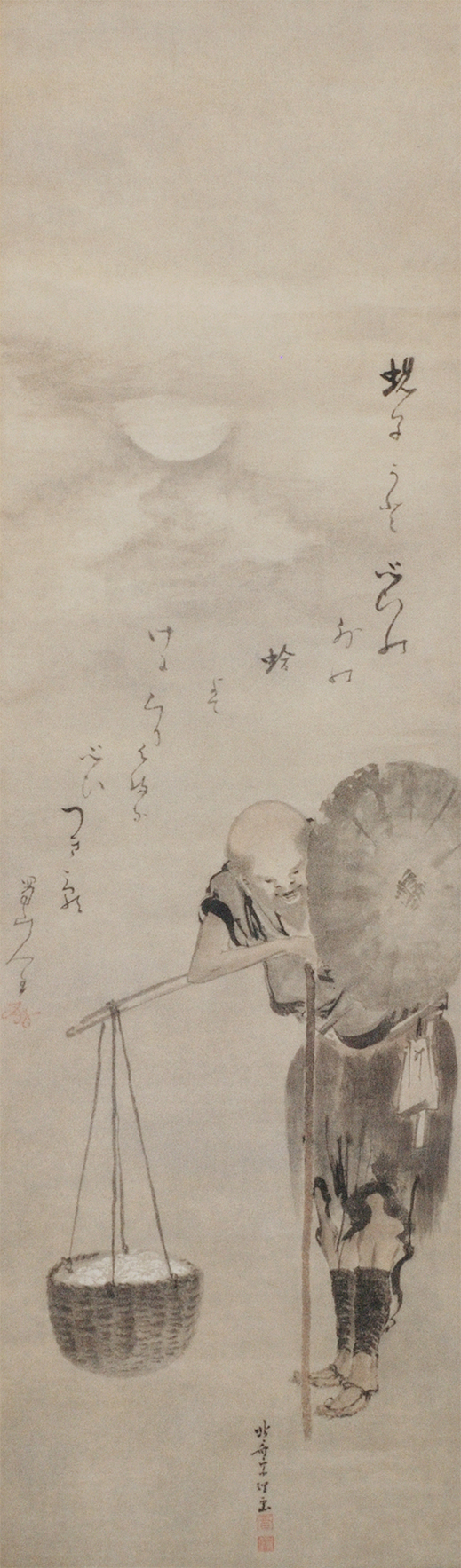

Clam Vendor, 1797-98. The white pigment used to paint the clams is made of their crushed shells.

|

Hokusai himself had engaged in different trades. From around the age of 14 he learned woodblock carving and is said to have earned his living that way for three years until he began his study of painting, which became his lifelong occupation. His first ukiyo-e were published within a year. But Hokusai's eye for detail had been honed from still earlier an age: as a boy he worked for a lending library, carrying books door-to-door that people would borrow for a small fee. In his spare time he copied their illustrations, thus cultivating his acute sense of detail while laying the foundation for what would become an encyclopedic knowledge of drawing and painting techniques.

One of the most talked-about works is a recent addition to the museum collection, on display through 19 May. Heretofore unknown, its provenance a mystery, Clam Vendor was brought to the museum's attention by an art dealer last year and is shown here in public for the first time. Its inscription, believed to have been added after Hokusai completed the work, is by poet Nanpo Ota (1749-1823), a prominent Edo-era literary figure who often collaborated with Hokusai and other artists.

The painting is of a vendor having set down his heavy load of hamaguri clams for a moment of rest, but Nanpo seems to have associated the figure with the legend of Xian-zi, a Tang-dynasty Zen monk who travelled China's countryside in a tattered robe, happily subsisting on a foraged diet of shijimi clams and prawns. Nanpo's verse plays on this blurring of identity in lines that humorously confuse the one kind of clam with the other.

|

|

Mount Fuji from Kanaya on the Tokaido Road from the series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, c. 1831.

|

In Hokusai's time, crossing the 1.3-kilometer Oi River in Shizuoka was a formidable part of a Tokaido highway journey. He portrays the scene at Kanaya, now Shimada city, on the river's west bank. For defense reasons shogunate policy forbade the establishment of a bridge or ferry service, so travelers had to hire porters to carry them and their parcels across. The fee varied according to the water's height: hip, waist, chest or shoulder. Women and those in the warrior class were conveyed, at extra charge, on wooden floats manned by several people; other travelers had to climb onto a porter's shoulders and hope for the best. These strong workers are said to have numbered as many as 1,200 at the end of the Edo period. When a bridge was finally built in the late 1870s, many turned to tea cultivation, founding what would become one of Shizuoka's greatest industries.

Dressing a Samurai's Hair, 1799 (on exhibit from 21 May).

|

While the exhibition lasts, in a separate gallery upstairs you can flip freely through replicas of all 15 volumes of Hokusai Manga, known in the West as Sketches by Hokusai. Considered the genesis of Japanese manga for their stop-action scenes, these thousands of drawings were published from 1814, when Hokusai was 55, until 1878, three decades after his death. Also on display through 9 June is a high-definition replica of Scenery on Both Banks of the Sumida River, a fascinating seven-meter picture scroll that starts at the Ryogoku Bridge and follows the river upstream all the way to the Shin-Yoshiwara pleasure quarter and inside to a banquet in progress. Painted in 1805, it was auctioned in Paris in 1902 and then lost to record until 2008, when it was rediscovered and eventually repatriated. Videos in English and Japanese explain its story in detail.

|

|

Simplified View of Tagonoura Beach at Ejiri on the Tokaido Road from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, c. 1831. Fishermen cast their nets as oarsmen navigate. On shore, people work at harvesting salt.

|

The Sumida Hokusai Museum is a short walk from the Edo-Tokyo Museum, which through 16 June happens to be hosting Traveling on the Edo Highways: A Journey of Shogun and Princesses. Seen in tandem, the two shows provide an interesting cross view of working- and ruling-class lives as they were led in and outside of Edo.

Poem by Minamoto no Muneyuki from the series One Hundred Poems Explained by a Nurse, c. 1835. Hokusai illustrates a nobleman's verse about the loneliness of a mountain village in winter with a scene of hunters congenially warming themselves at a fire.

|

Unless otherwise noted, all artworks are by Katsushika Hokusai and are the property of the Sumida Hokusai Museum. Not all of those introduced here will be on view after 20 May, when the museum will close for a day to change the exhibits. |

|

|

Susan Rogers Chikuba

Susan Rogers Chikuba, a Tokyo-based writer, editor and translator, has been following popular culture, architecture and design in Japan for three decades. She covers the country's travel, art, literary and culinary scenes for domestic and international publications. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|