|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese residents of Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Weaving a Story: From the Modern to the Contemporary in Japanese Art

J.M. Hammond |

|

|

|

Innovation, inspiration and the incorporation of new ideas have long been part of art in Japan as much as inherited technique and tradition. Still, no other period has seen such rapid and radical transformation in Japanese art as the 20th century. A new exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo attempts to underscore this journey by examining two conceptual approaches -- that of editing (the acceptance or rejection of disparate ideas and techniques) and that of weaving (incorporating these elements into new works or styles).

Why such an exhibition now? Weavers of Worlds: A Century of Flux in Japanese Modern/Contemporary Art marks the museum's reopening after a three-year closure so it could make improvements to the building and upgrade its equipment (it was established in 1995). The museum is taking this as an opportune time to revisit its collection of over 5,200 pieces and put them into context.

Weavers of Worlds highlights over 600 works from, roughly speaking, the 20th century. More precisely the exhibition takes as its starting point the year 1914 and runs up to the present day. Whatever year is chosen to begin an examination of modern art generally -- let alone that of Japan in particular -- is bound to be contentious. The reasoning behind this show's choice of 1914 is that the outbreak of World War I limited the import of art journals that had been introducing Japan to the latest developments in European art, and that by this time artists in Japan were no longer simply absorbing these new ideas but were actively selecting and editing them into their artistic productions.

To convey this idea, one of the first artists the exhibition focuses on is Ryusei Kishida. Kishida was a student of Seiki Kuroda, one of the first figures in the late 19th century to energetically introduce Japan to Western-style oil painting. Kishida was, in phases, enamored of Vincent van Gogh and other post-Impressionists, and then, in particular, of Albrecht Dürer. He himself admitted that he could be charged, initially, with copying the styles of these masters, but after learning their techniques, he could incorporate what he required into his own vision. The exhibition posits Kishida as an example of a Japanese artist of the period who sifted through and edited the new information and ideas he was exposed to, and it is successful enough in this regard.

|

|

Ryusei Kishida, Self-Portrait Sent to Mr. Tsubaki, 1914 |

Yet, as important as Kishida is, it is curious that the exhibition did not pick up on an artist like the more colorful Tetsugoro Yorozu, his fellow student under Kuroda's tutelage. Yorozu "weaved" into his work -- even a few years before the 1914 starting point the show proposes -- many of the more avant-garde developments in European art, such as Cubism and Expressionism, that Kishida rejected. Such a contrast in this presentation would have been welcome, but as the museum doesn't own any Yorozu pieces, this highlights how collection-led exhibitions, by nature, subtly shape narratives based on the works they have available.

The exhibition spreads across three of the museum's many floors, and has 14 sections in all -- too many to unpack here -- each focusing on a particular concept or area of activity. The section "Before and After the Earthquake Disaster" shows how, early in the 1920s, the arrival of several Russian artists introduced Japan to new developments such as Russia's response to Cubism and Futurism, and its homegrown ideas of Constructivism. These concepts were most visibly taken up by the Mavo group led by Tomoyoshi Murayama, who had already plunged into Dada and Expressionism while in Germany. A selection of this group's output -- including collages, linocuts, and their self-published magazine -- is on display here.

|

|

Masao Tsuruoka, Heavy Hand, 1949 |

In comparison, it is more difficult to unravel the threads of inspiration that Tai Kanbara, working at around the same time, wove together in his work, for they often seem to be more musical, thematic, and philosophical than strictly visual. Two of his abstract, or near-abstract, canvases are on display here, including the vibrant Flowing Life Energy (Symphony No. 35).

The exhibition also shows how woodblock artists responded to Modernism by moving away from Edo-era-style ukiyo-e images of courtesans and the like and addressing aspects of modern life. A new breed, the Sosaku Hanga (Creative Print) artists, no longer limited themselves to designing the images but also carved, printed and published them -- often in their own journals.

Created by some representatives of this movement, the series A Hundred Views of New Tokyo includes not only depictions of the city's bridges and rivers, but also its department stores, subway, and even a garbage incineration plant. Also featured -- though perhaps more use could have been made of him -- is Koshiro Onchi, who took woodblock prints into the realm of abstraction with his focus on expressing mood and feeling through shape, color and line.

|

|

Yuki Katsura, Resistance, 1952 |

Another room in the exhibition explodes with color and energy. In the 1950s the arrival of art critic Michel Tapie from France introduced Japanese artists to the abstract style of Art Informel, which emphasized physicality and texture (including various new materials). Female Japanese artists were breaking through around this time, and they provide some of the most colorful and expressive paintings here -- such as those by Hideko Fukushima and Atsuko Tanaka -- as well as some perplexing installations. In a more political vein, Yuki Katsura has a few of her works on display. There are also several by Setsu Asakura, who started out painting Nihonga (Japanese-style art) with traditional Japanese pigments, but broadened her thematic range outwards to include laborers and other scenes of Japan's modernization, such as the construction of Tokyo Tower.

Entering the section called "Weaving Images," the viewer is greeted with a wall of Andy Warhol's silkscreen prints of Marilyn Monroe, somewhat surprising in an exhibition of Japanese art -- but the logic becomes clear when you turn around and see Etsutomu Kashihara's My Methods Inspired by Marilyn (1972-75). In particular, Kashihara seems enthused by the way silkscreen allows him to easily play with negative and positive space, as he leaves Marilyn's face blank and emphasizes the hair and other details that frame it.

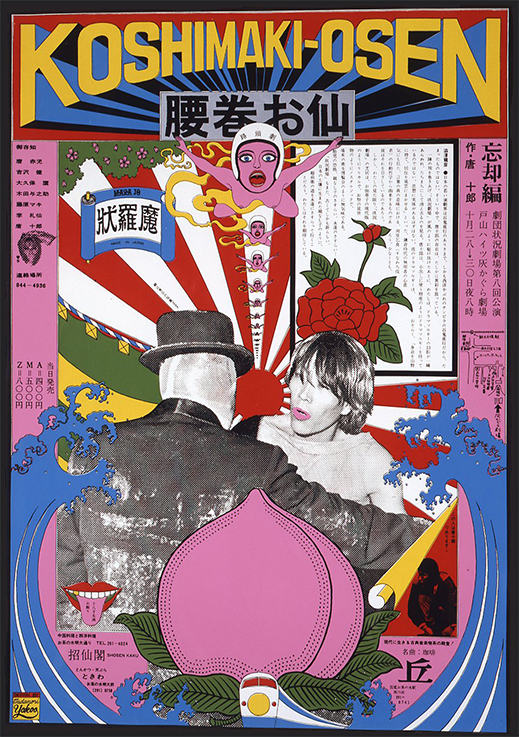

Nearby are some posters by Tadanori Yokoo that have become as iconic of Japanese pop art as Warhol's Marilyn is of American pop art. Included here is Koshimaki-Osen, a multi-colored poster for a theatre production, part of the Tokyo underground scene Yokoo was associated with in the 1960s.

|

|

Tadanori Yokoo, Koshimaki-Osen, Gekidan Jokyo Gekijo, 1966

|

As the term "modern art" became a category marker for work of a certain historical period and gave way to the term "contemporary art," one narrative posited these "contemporary" productions as increasingly transnational and entangled in the spreading web of globalization, rather than necessarily representing any national art scene. Weavers of Worlds features many of the established Japanese contemporary artists one might expect -- Takashi Murakami, Yoshitomo Nara, Makoto Aida, Yasumasa Morimura, and more -- who do indeed have an international aspect to their careers. Yet these artists also bring a certain Japanese sensibility and thematic thrust to their take on contemporary art that puts the assumptions of transnationalism under question.

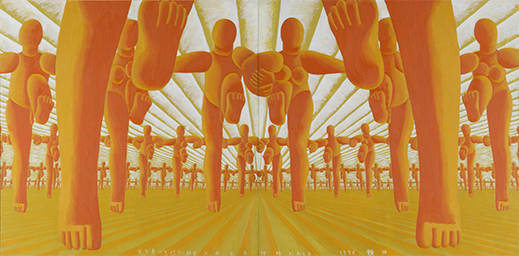

Works representing this generation include a number of roughly textured acrylic paintings by Takashi Murakami from 1997, before he embarked on the colorful, smoothly-executed flower paintings he is known for. Another highlight is the installation Rocking Mammoth by Kenji Yanobe, a huge animal figure made up of machine parts, iron and other materials. The exhibition also introduces the work of young artists who have launched their careers in the last decade or so, among them a video piece by the guerilla art group Chim↑Pom, and Kazuki Umezawa's interesting mash-up of imagery of the contemporary world, consisting mainly of digital data culled from the Internet.

How successful is Weavers of Worlds? There is certainly plenty to see, most of it of high quality, which offsets the occasional work that simply seems dated rather than relevant to today. As the exhibition covers so much ground, it can, inevitably, offer only glimpses of the manifold developments in Japanese art it addresses. However, for those who already know something about Japanese art of the 1910s to 2010s, as well as for those new to it, there are surprises enough in store.

|

|

Yasumasa Morimura, Portrait (Shonen1, 2, 3), 1988

|

All images courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo. |

|

|

J.M. Hammond

J.M. Hammond researches modernity in Japanese art, photography and cinema, and teaches in Tokyo, including as a faculty lecturer in the English department at Meiji Gakuin University and at Gakushuin University. He has written about art for The Japan Times for over a decade. His essays include "A Sensitivity to Things: Mono No Aware in Late Spring and Equinox Flower" in Ozu International: Essays on the Global Influences of a Japanese Auteur (Bloomsbury, 2015) and "The Collapse of Memory: Tracing Reflexivity in the Work of Daido Moriyama" for The Reflexive Photographer (Museums Etc, 2013) [reprinted in the same publisher's 10 Must Reads: Contemporary Photography (2016)]. He has given various conference papers, including at the University of Hong Kong and the University of Oxford. |

|

|

|