|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese residents of Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Understanding the Design of Architect Tadao Ando: A Reading of his Early Drawings

James Lambiasi |

|

Installation view, Early Drawings of Tadao Ando: Autonomy and Dialogue |

Tadao Ando is not only one of the most accomplished architects in Japan, but has evolved into such an icon of global stardom that one tends to forget his humble and unconventional beginnings. Born in Osaka and originally a professional boxer, he trained himself as an architect and established Tadao Ando Architect & Associates in 1969. His first projects were small residences that challenged the concept of dwelling, and also highlighted how the flexibility of traditional Japanese lifestyles could adapt to such shockingly new spaces. The architectural world was enraptured by the novelty of Ando's bold designs, and thus, at a point in his career where he was still developing as an architect, he was catapulted onto the world stage of design. It is this rise to stardom that makes the initial stage of Ando's career all the more intriguing. In an amazingly detailed exhibition, the National Archives of Modern Architecture, located next to the Kyu-Iwasaki-tei Gardens in Yushima, Tokyo, has investigated this part of Ando's career in Early Drawings of Tadao Ando: Autonomy and Dialogue, which is showing until 23 September.

This study of "autonomy and dialogue" in Ando's early drawings addresses an important aspect of the development of his design. Autonomy refers to the individual will of both the house and its inhabitants. By stripping away conventional details of residential living and leaving essentially exposed concrete, steel, and glass, Ando intended to create a less defined residential building while fostering a deeper relationship between humans, space, light, and air. Or, in other words, his houses were not just objects, but an opportunity for dialogue between people and their homes.

In addition to helping us understand this design concept, the exhibition offers a rare chance to intimately view the actual drawings of these early iconic buildings. It is significant that the drawings were mainly created before 1990; after that his office began producing drawings by computer with CAD software. While viewing these works, it is important to take yourself back to this time and understand the drawing process that architects utilized to visualize buildings. Only after completion of a hand-drawn plan and elevation could one extrapolate the information of the lines into a three-dimensional drawing. Today it is the opposite: buildings are assembled within computer spaces, and the two-dimensional plans are automatically generated. The drawings of this exhibit represent a time when the economy of superimposed drawings helped to save money on paper, and the legibility of pencil drawings depended on the skill of the draftsperson to rotate and angle the pencil just right so as to keep lines sharp.

|

|

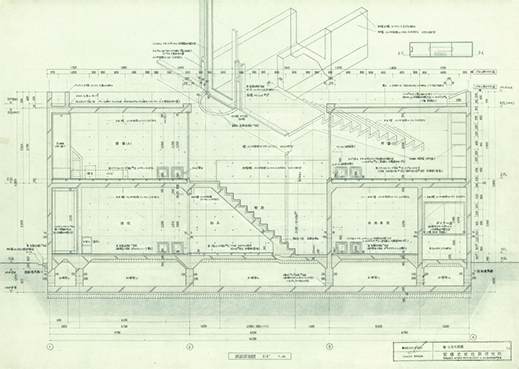

Row House in Sumiyoshi - Azuma House: Detailed section drawing, pencil and ink on tracing paper |

Installation view: Drawings and model of Row House in Sumiyoshi - Azuma House |

When explaining his drawings, Ando is quoted as saying, "I want to condense the intent behind the design into a single drawing. Drawings are an architect's words." This is evident in the hand-drawn section of Row House in Sumiyoshi. While minute details of the pencil drawing provide a view into the construction of the space, superimposed above it is an isometric view of the famous connecting bridge. Just as the house created a dialogue between dwelling and the elements of light and air, the drawing offers its own rendition of simultaneity between precise detail and expanding space.

Also intriguing about the early work of Ando is the artistic finesse of his drawings. Occupying one wall are four of his works, all rendered in silkscreen print and color pencil. Again, the process of drawing is telling of his overall design philosophy. Abstract layering of shades of blue along with minimal representation of detail display the building as if it were an ancient ruin, fulfilling its duty as human shelter yet never losing its autonomous presence to shape spaces by playing with light and shadow. His wooden models are equally austere, limiting materials to mostly wood in order to highlight primitive forms and the depth of their shadows.

Installation view: Drawings and model of Rokko Housing I |

Installation view: Drawings on background wall, silkscreen print and color pencil on paper |

I must admit that for myself, as an architecture student in the late 1980s, it is a pleasure to see first-hand the drawings that sparked my desire to know more about Japan and led to the decision to work as an architect in Tokyo 30 years ago. I hope that by visiting this exhibition you can also discover your own understanding of these drawings which so concisely express Ando's powerful convictions. The exhibition is free to the public and complete with English translations, so I encourage all to take this opportunity to see and experience the fascinating origins of Ando's prolific career.

All images by permission of the National Archives of Modern Architecture, Agency for Cultural Affairs. |

|

|

James Lambiasi

Following completion of his Master's Degree in Architecture from Harvard University Graduate School of Design in 1995, James Lambiasi has been a practicing architect and educator in Tokyo for over 20 years. He is the principal of his own firm James Lambiasi Architect, has taught as a visiting lecturer at several Tokyo universities, and has lectured extensively on his work. James served as president of the AIA Japan Chapter in 2008 and is currently the director of the AIA Japan lecture series that serves the English-speaking architectural community in Tokyo. He blogs about architecture at tokyo-architect.com. |

|

|

|