|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese residents of Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Obsessive Observation: The Legacy of Maruyama Okyo

J.M. Hammond |

|

Maruyama Okyo, Sketches Handscrolls (Scroll 1), 1771-72, Important Cultural Property, Chiso Co., Ltd. (Tokyo exhibition, second half; Kyoto exhibition, second half)

|

Active in 18th-century Kyoto, Maruyama Okyo left a mark on Japanese art far exceeding the legacy of his own distinguished oeuvre. His activities extended to teaching and mentoring other artists and helping establish a new visual tradition in Japanese art. Taking a fresh look at Okyo and artists associated with him is a new exhibition, Legendary Kyoto Painting from Maruyama Okyo to the Modern Era, at the University Art Museum, Tokyo University of the Arts (after which it will be held at the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto).

Okyo (1733-1795) was working at a time when the art world of Kyoto and beyond was dominated by a limited number of schools, or traditions, such as the Kano and the Tosa. The multi-generational family-run Kano school had for a number of centuries been scooping up many of the lucrative official Shogunate commissions and other high-profile artistic projects, and though its style was, perhaps, losing some of its luster, as a force it still held much sway.

|

|

Maruyama Okyo, Peacocks and Peonies, 1771, Important Cultural Property, Shokokuji, Kyoto. (Kyoto exhibition, second half) |

Even so, there were still temples to decorate and numerous other ways for artists such as Okyo to make a living, and one way of standing out was to take a fresh approach to picture making. This Okyo did, with a penchant for carefully and obsessively observing scenes, especially animals, from real life. This set him apart from the standard practice of the Kano school, whose members learned their craft from pattern books, handed down by senior artists, that showed them how to draw and paint established forms and motifs. Okyo's dedication to observing directly from nature influenced other artists, and this serves as a common thread tying together many of the works in the exhibition. About 120 works are included here, even if those by Okyo himself account for no more than a dozen.

In the first part of the show, entitled "It All Began with Okyo," the artist makes his appearance with an impressive set of fusuma sliding doors, Pine Trees and Peacocks, from Daijoji temple in Hyogo Prefecture, painted at the end of his life. The panels are painted purely in black ink on gold paper, yet depending on the light at any time, the ink on the luminescent backdrop can appear to be a deep blue. The eyes of the peacock's feathers would seem to be one example of this, at least on the afternoon of this writer's visit.

|

|

|

|

Maruyama Okyo, Pine Trees and Peacocks (8 of 16 panels), 1795, Important Cultural Property, Daijoji, Hyogo. (Top: Tokyo exhibition only; bottom: Kyoto exhibition only) |

This work is one of five from Daijoji on display together here. Two of these are by Goshun (1752-1811), who worked with Okyo and studied his style later in life, but before that had dedicated his career to Chinese-influenced literati-style art, which takes a somewhat subjective and poetic stance toward depicting objective reality, predominantly landscapes. Mountain Peaks above the Clouds is in this earlier style. The pair of screens displays the himashun technique, which renders the uneven lines of a mountain's rocky surface in undulating, somewhat soft strokes (compared to the dry, hard brushstrokes some other literati artists used to convey a chiseled, scraggly rock surface). In Goshun's work, the soft effect is heightened by his delicate, pale coloring. The artist learned this technique from his master in literati painting, the great poet-painter Yosa Buson (1716-1784), and a work in which Buson employs this technique -- Cottage in a Bamboo Grove -- is shown here.

After Goshun began working with Okyo, he didn't simply switch from one style to another, but extended his repertoire of techniques and subject matter, and after Okyo's death fused the literati style with Okyo's to found what is known as the Maruyama-Shijo school. On display is a work that shows what Goshun learned from Okyo in the close study of animals. Peacock on a Rock suggests Goshun took up Okyo's practice of observing carefully from life, but the exhibition points out that he used a simpler approach, with fewer brushstrokes, than Okyo did.

|

|

|

|

|

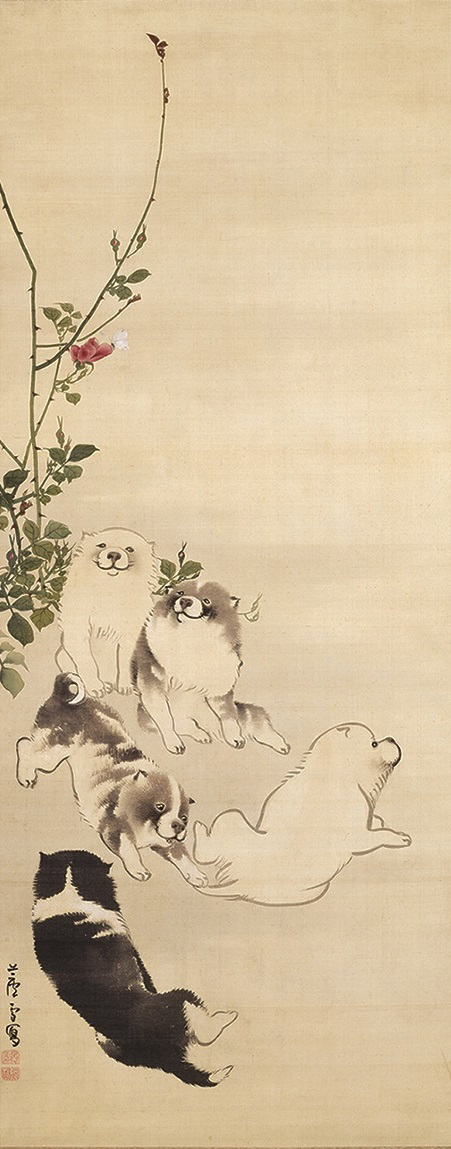

Nagasawa Rosetsu, Five Puppies, a Rose and Butterfly, c.1794-99, Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art (Kimura Taizo Collection). (Tokyo exhibition, first half; Kyoto exhibition, second half)

|

Okyo largely eschewed painting phoenixes, dragons and other mythological creatures, as his interest lay in the wonders of the world around him. This drew him to try to capture the charms of everyday scenes, and, in fact, Okyo is believed to have virtually kick-started Japan's love of the kawaii with his pictures of fluffy little puppy dogs and other cute animals. The exhibition shows how Okyo's attention to the immediate influenced many other artists in his wake. Nagasawa Rosetsu (1754-1799), one of the so-called "eccentric" artists attracting interest today, actually studied under Okyo and in some works shares his fondness for the cute. In Rosetsu's Five Puppies, a Rose and Butterfly, the tiny puppies are as adorable as Okyo's, but they are no mere copy -- the exhibition points out they are not as round in shape. The splash of red provided by the rose contrasts with the soft white of the puppies' fur, and brings the work to an understated but complete whole.

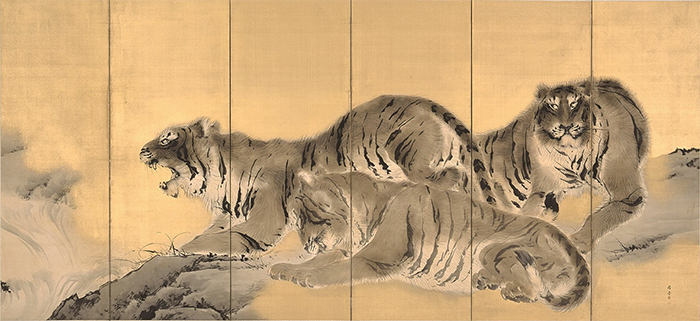

The exhibition shows how some schools were known for their particular skill at depicting certain animals, such as the Mori school's pictures of monkeys, or the tigers of the Kishi school. For the Meiji-period work Tigers, Kishi Chikudo (1826-1897) of the Kishi school used tigers from an Italian circus as models, capturing the animals' ferocious strength ready to be unleashed.

|

|

Kishi Chikudo, Tigers (right screen), 1890, Chiso Co. Ltd. (Tokyo exhibition, first half; Kyoto exhibition, second half) |

Indeed, there is a notable concentration by this show on landscapes and pictures of animals, as artists followed in the direction set by Okyo's devotion to observations from nature. However, a lesser-known side of Okyo's output is his bijin-ga, or pictures of beautiful women, which is the focus of the last of the galleries. The delicacy of his rendering of Japanese beauties was said to have influenced Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858) and is also reflected in the work of the female painter Uemura Shoen (1875-1949), one of whose bijin-ga is on display here.

|

|

|

|

|

Maruyama Okyo, Eguchinokimi, 1794, Important Art Object, Seikado Bunko Art Museum. (Tokyo exhibition, first half)

|

Some visitors may find that the pastel-like softness and coloring of Genki's Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons reminds them too much of an old-fashioned chocolate box, but overall the quality here is very high. Legendary Kyoto Painting allows visitors to not only view some top-rated works by Okyo, as well as excellent works by other artists that are not often seen, but also to learn something of Okyo's impact on subsequent artistic developments in Japan.

Note: Many of the works listed in this exhibition are on display only in Tokyo or Kyoto, or only in the first or second half of either show.

All images are courtesy of the University Art Museum, Tokyo University of the Arts. |

|

|

J.M. Hammond

J.M. Hammond researches modernity in Japanese art, photography and cinema, and teaches in Tokyo, including as a faculty lecturer in the English department at Meiji Gakuin University and at Gakushuin University. He has written about art for The Japan Times for over a decade. His essays include "A Sensitivity to Things: Mono No Aware in Late Spring and Equinox Flower" in Ozu International: Essays on the Global Influences of a Japanese Auteur (Bloomsbury, 2015) and "The Collapse of Memory: Tracing Reflexivity in the Work of Daido Moriyama" for The Reflexive Photographer (Museums Etc, 2013) [reprinted in the same publisher's 10 Must Reads: Contemporary Photography (2016)]. He has given various conference papers, including at the University of Hong Kong and the University of Oxford. |

|

|

|