|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese residents of Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

By the Numbers: A Trip through Time and Space

Christopher Stephens |

|

The first few years of Norio Imai's Daily Portrait (1979-), an ongoing project in which the artist takes a picture of himself every day. |

As Pythagoras put it, the universe is built on numbers. Arithmetical values can be ascribed to virtually any entity or phenomenon from heat to heartbeat, mass to music to better understand its nature. The four artists featured in Art Trip Vol. 03: In Number, New World, an exhibition on view through 9 February at the Ashiya City Museum of Art & History in Hyogo Prefecture, escort us to unfamiliar places that are essentially bound up with numbers.

Norio Imai (b. 1946) got his start as an artist while still in high school with a 1964 solo exhibition titled Testimony of a 17-year-old. The show, held at an Osaka gallery, happened to catch the eye of Gutai Art Association leader Jiro Yoshihara (1905-72) who, hoping to infuse the group with youthful energy, invited Imai to join Gutai the following year. One of the so-called "third generation" of Gutai artists, born in the late '30s and early '40s, Imai remained with the group until it disbanded in 1972. Unfortunately, his seven-year tenure with the legendary collective has tended to overshadow a career that spans more than half a century. The Ashiya exhibition includes nine pieces by Imai from the post-Gutai era, most notably the Daily Portrait series. Based on an idea that many have probably entertained but few have had the stamina to see through, the work consists of daily self-portraits of the artist taken with an instant camera in which he poses expressionless while holding the photograph from the previous day. The date is written in the white border of the picture with a black marker. Begun in 1979, the project is ongoing. Each year's worth of photographs is neatly stacked inside an acrylic box, with the December 31st entry on top. Next to the 2020 container is a pile of envelopes that Imai has sent to the museum every day of the exhibition with the latest shot inside. To mark the 25th year of the project, in 2005 Imai made a nine-minute video called Temporal Ensemble: Daily Portrait, showing every picture taken up until that point in rapid succession. Since only the last picture in a given year is visible in the original work, this helps convey the passage of time and the gradual physical changes that have occurred over the years.

|

|

Michiko Tsuda, You would come back there to see me again the following day. (2019). Kumi Sugai's Architecture Series (1974) is visible on both sides of the main space. Saburo Murakami's Work (1962) and Work (1961) are displayed on the back wall to the right of the exit, and Kazuo Shiraga's Shoko (1989) is at the far end of the right wall. |

One special feature of the exhibition is the inclusion of works from the museum collection as selected by each participant. While Imai's choices are displayed separately from his works, the artist Michiko Tsuda (b. 1980) incorporates into her installation a series of silkscreen prints by Kumi Sugai (1919-96), two paintings by the Gutai artist Saburo Murakami (1925-96), and one by his colleague in the group, Kazuo Shiraga (1924-2008). Occupying half of one of the two large galleries on the museum's second floor, Tsuda's own work, You would come back there to see me again the following day., centers on several picture frames hanging from the ceiling in a seemingly haphazard formation. Some of the frames are empty, while others contain mirrors or screens that present us with projections of ourselves from unexpected angles. Gradually, it becomes clear that each of the frames has been carefully positioned to capture a particular scene. Even the empty frames change the atmosphere in the room by creating a sense of distance between us and the things we see through them. Regardless of where we look, the nine prints in Sugai's Architecture Series (1974) are always visible. Inspired by the blur of colors and shapes Sugai saw out the window of his beloved Porsche while speeding down the highway, the works depict snatches of clouds in the blue sky and simple geometrical patterns. The only frame from which Sugai is absent encloses a video image of the opposite corner of the room, where the Murakami and Shiraga pictures hang. This footage, shot each day of the exhibition and screened on the following one, adds another temporal dimension to the space. Tsuda also provides a handout of "movement scores" for the Gutai artists' works. Recalling diagrams of dance steps, the scores are Tsuda's interpretations of the speed and motion that went into making the works. Murakami's paintings belong to a vertical realm involving violent movements of the arm, while Shiraga's picture, created by sliding his feet across a canvas on the floor, embodies a horizontal one.

|

|

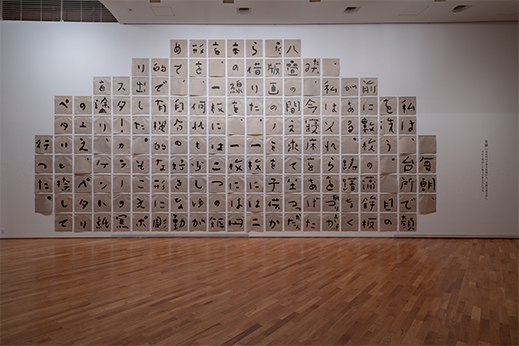

Yuta Nakamura's Abstracting Kamaboko (2019), a clay-on-paper reproduction of Saburo Hasegawa's handwritten text. |

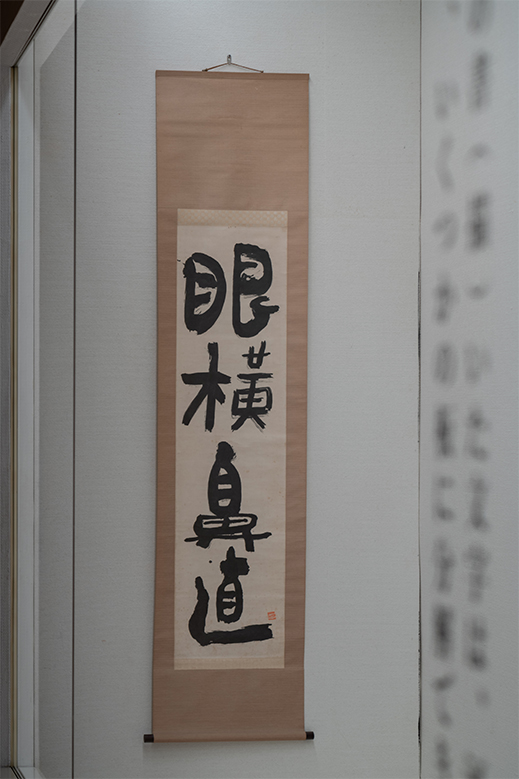

For viewers in search of an immediate visual buzz, Yuta Nakamura's installation Abstracting Kamaboko (2019), which takes up the remainder of the gallery, may not initially seem very satisfying. A bit of perseverance, however, leads to a better appreciation of this complex and ingenious work. Choosing Gannobichoku (c. 1956), a calligraphy scroll by the pioneering abstract painter Saburo Hasegawa (1906-57), from the museum collection, Nakamura (b. 1983) employed his signature approach of "observation, postulation, experimentation, and consideration" to expand his findings into a sprawling work. He began by analyzing the scroll, which bears a four-kanji phrase meaning "the eyes are horizontal, the nose vertical" -- the Zen priest Dogen's explanation of what he learned on a trip to China. Next, Nakamura discovered that Koichi Kawasaki (1952-2019), a former director of the Ashiya City Museum, had developed a numbering system to make sense of the small wooden blocks (recycled boards from packages of kamaboko fish cakes) Hasegawa had carved into printing blocks. This led Nakamura to examine the individual pieces of Hasegawa's distinctive handwritten characters by reproducing a text in which the artist explained his printmaking technique. After meticulously rendering Hasegawa's handwriting with clay on paper, Nakamura went so far as to replicate the lines that Hasegawa had drawn through some sections of the text with hemp twine. He then arranged the 150 or so sheets of text, each containing a single character like the squares on a sheet of manuscript paper, on the wall to resemble a loaf of kamaboko in cross section. Finally, Nakamura completed the circle by affixing four clumps of mortar to a thin strip of ceramic tiles to create an abstract approximation of Hasegawa's calligraphic work.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Saburo Hasegawa, Gannobichoku (c. 1956).

|

|

Mortar and tile sculpture inspired by Gannobichoku in Yuta Nakamura's installation Abstracting Kamaboko (2019). |

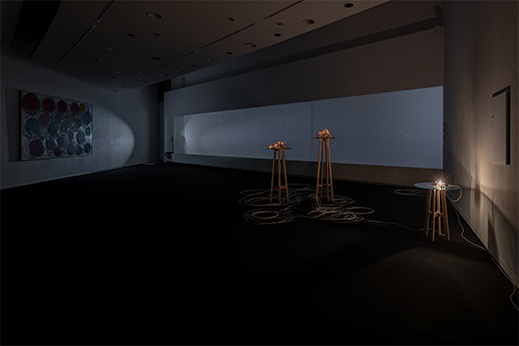

From the minute we set foot in the museum, we are confronted with distant rumblings. The nature of these unnerving sounds is finally revealed in the last room, which contains Tsuyoshi Hisada's (b. 1981) installation Artist (2019). Behind two heavy curtains is a dark space filled with earsplitting peals of thunder and gusts of wind, which seem to be emanating from an opaque display case with the appearance of a cloudy sky. Near the entrance to the room are three tables of varying heights covered with a tangle of bubble-shaped light bulbs, which slowly brighten before fading again. At the base of the tables is a sea of electric cords. These excessively long cables are artfully wound into a series of circles, recalling pools of water, as if they have been deposited there by the aural rainstorm. They also have clear parallels with Atsuko Tanaka's Work (1963), Hisada's selection from the museum collection, which hangs on a wall across the room. Tanaka (1932-2005), a founding member of the Gutai group, repeatedly dealt with the motifs of electric cables and light bulbs in her paintings, perhaps most memorably in Electric Dress, a 1956 piece fashioned out of a cluster of colored lights and cords that the artist wore like a dress. Without the aid of spotlights, we struggle to pick out the finer points of Work, lit solely by a dim, fluctuating bulb in the corner of the room. This enables us to move beyond the vivid colors and shapes of the painting and concentrate instead on the texture and quantity of paint on the canvas. Meanwhile, on the other side of the room, a clock-like mechanism turns silently in the upper left corner of a white panel. With a tiny magnifying glass embedded in one end, the lone hand in Hisada's crossfades (2013-) counts down the seconds but is positioned a little too high for us to catch sight of the numbers.

Distinctly different but subtly linked, the works in this exhibition turn the quantifiable into something elusive. Never have numbers looked so good.

|

|

Tsuyoshi Hisada's Artist (2019), with Atsuko Tanaka's Work (1963) on the left wall and Hisada's crossfades (2013-) on the right. |

All photos by Nobutada Omote, courtesy of the Ashiya City Museum of Art & History. |

|

|

Christopher Stephens

Christopher Stephens has lived in the Kansai region for over 25 years. In addition to appearing in numerous catalogues for museums and art events throughout Japan, his translations on art and architecture have accompanied exhibitions in Spain, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, South Korea, and the U.S. His recent published work includes From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and Gutai: Splendid Playground (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2013). |

|

|

|