|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Paper City: A Close-up View of the Tokyo Firebombing

Susan Rogers Chikuba |

|

Paper City director Adrian Francis (center) and his crew film a meeting between Lower House representatives and survivors of the firebombings in March 2016. Most of the footage was shot on and off between 2015 and 2016. Photo by Wataru Sekine

|

Unprecedented in scale and intent, the incendiary air attack on eastern residential Tokyo by 334 U.S. B-29 bombers just after midnight on March 10, 1945 unleashed a firestorm that would kill more than 100,000 civilians and render one million homeless by dawn. In Paper City, a feature-length documentary slated for completion this year, Australian filmmaker Adrian Francis directs an intimate lens onto the personal experiences of three elderly survivors determined to leave a public record before they pass away.

Michiko Kiyooka stands on Kototoi Bridge, where an estimated 1,000 people perished in the midnight air raid on March 10, 1945. She and her family took refuge beneath it until the streams of fire drove them into the icy Sumida River. Kiyooka, then 21, survived by clinging to a mooring post until dawn. Photo by Brett Ludeman

|

Francis, 45, is a 15-year resident of Tokyo. "Like many Australians of my generation," he says, "I grew up with anecdotes of the cruelty suffered by allied civilians and POWs at the hands of the Japanese military. But apart from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, I was taught nothing about how ordinary Japanese civilians experienced the war." That changed when he saw the Errol Morris documentary The Fog of War. In it, Robert S. McNamara, the U.S. secretary of defense during the Vietnam War, addresses his earlier role as a World War II statistical planner for the firebombing of Tokyo and more than 60 other cities across Japan. In a numbing

montage that puts the immensity of the loss of life in perspective, McNamara repents the immorality of fighting a war out of all proportion to its objectives, asking "How much evil must we do in order to do good?"

"I had already been a Tokyoite for many years when I saw this," Francis says, "but had never seen any physical traces or heard stories of what happened. Nothing in the city had pointed me to it. Berlin has its Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, Hiroshima has the Atomic Bomb Dome -- places where people come from around the world to learn, mourn, and pay their respect," he says. "But in Tokyo, where tens of thousands lost their lives in a single night, hardly a trace remains, and rarely does anyone ever even talk about it." With Paper City Francis gives a lasting voice to the survivors, a message we need to hear as civilian-targeted bombings rage on in Syria, the Gaza Strip, Afghanistan, and elsewhere.

|

|

Two inscriptions of the date March 10 on a family tombstone mark the deaths of Kiyooka's father and sister. "We were lucky. So few were able to locate or even identify their loved ones," she says. Photo by Brett Ludeman

|

With no footage of the scenes that still play in the survivors' minds, Francis offers instead an immediate, intimate relationship to them. The handheld camera stays low, close to their bodies, near the heart. As they navigate their days with flip phones, fax machines, canes, and hearing aids, he lingers on the textures of their lined faces and parchment skin. "The physical proximity to these elderly characters captures the rhythms and details of their slow-moving world," he says. "Sometimes they speak candidly, at another times they fall silent as they retreat into memory, or when words cannot convey what they saw." Subtle shifts in his subjects' gestures, breath, and moods suggest mindscapes that stretch from memory onward through undulating fields of worry and hope.

|

|

Hiroshi Hoshino was 14 on March 10, 1945. Haunted by the city littered with corpses, he devoted himself upon retiring to civilian peace campaigns. Looking out over a park that was one of many mass burial sites, he says, "I was just a kid. Those are my childhood memories. That's why I've put everything into this for 20 years, body and soul." Photo by Brett Ludeman |

"I want people to understand this . . ." says Hiroshi Hoshino, falling quiet as he sits on a bench in a park where thousands had been buried. A fellow survivor continues the thought. "Unless someone told you, you'd never know." Hoshino, a teen at the time, was mobilized along with other boys to collect bodies from the Kitajikken River and from air-raid shelters, where people had literally steamed to death, and transport them to mass burial sites. "Sheets of metal were everywhere -- it's all the fire left," he explains. "So we would pile corpses on those, fashion ropes of metal wire, and pull them through the streets that way." To drag bodies from the river, they were given firefighters' hooks. "It wasn't only Sumida ward," they continue, completing each other's sentences, "it was like this everywhere."

After retiring, Hoshino devoted himself to petitioning the government to recognize its responsibility for the civilian toll. "As a 14-year-old of course I was angry about the war, angry at the American forces. But I also saw Japanese soldiers in full formal dress marching through the streets after the ceremony for Army Commemoration Day. eHow dare they,' I thought. Here we were, stunned and burned, limping in our tattered clothes, refugees in our own city. If those strong soldiers cared so much for Japan, why couldn't one of them stop and carry my mother or sister to help them along?"

|

|

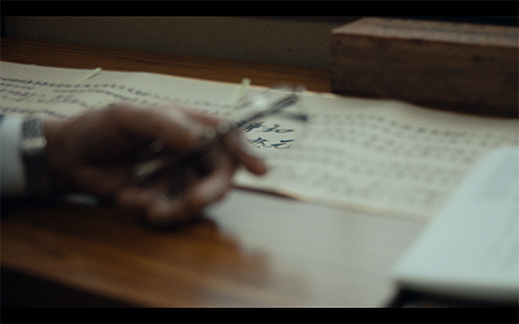

A scroll inscribed with the names of all 789 inhabitants of Morishita 5-chome who perished in the March 10 bombing stretches out before Minoru Tsukiyama, who was 16 at the time. "More than 100,000 people died that night. And yet ours is the only district that has been able to collect the names of every fallen resident." Photo by Brett Ludeman |

Minoru Tsukiyama has lived all his life in Morishita 5-chome, a district in Koto ward. "By March 1945 a third of the residents had evacuated to the countryside. Of the 1,000 who remained, nearly 80 percent died that night." Their names are inscribed on a scroll that the town council spent decades researching and amending, to ensure that all were accounted for and every last kanji recorded accurately. "For 70 years we've held annual memorial services faithfully for those who perished here. It's a way of showing respect," Tsukiyama says, pointing out that entire families were lost that night. "There are no descendants left to remember those souls. We don't have their cremains or any keepsakes. Their graves are empty. Looking after them this way is the humane thing to do. It's our duty," he says.

Riding in a taxi, Tsukiyama recalls walking down the same avenue that night, after the bombing. "It felt disrespectful to step over the dead. But there was nothing to be done about it. Corpses lay everywhere." In other scenes Tsukiyama reads from an essay he wrote 40 years ago, recounting the night, the bodies burned beyond recognition. The handheld camera moves ever so slightly, in time with the breath.

|

|

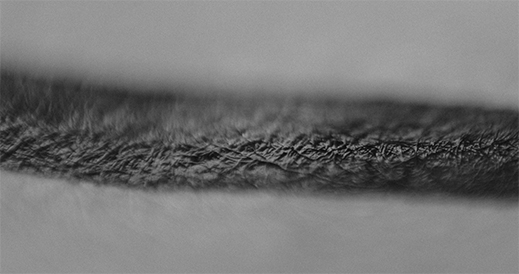

The film title and chapter markers are the brushwork of Hiromi Edo, pictured

here with Francis. Her calligraphy will also feature as kinetic breathing points in the film, a highly stylized artistic motif that is at once physical and powerful. Photo by Max Golomidov |

The March 10 raid was one of more than 100 that eventually laid waste to 60 percent of Tokyo, but it was the first designed to destroy a residential area. The B-29s flew in low, at 1,500 to 2,700 meters rather than the conventional 7,000 or 10,000. Their machine guns had been removed in order to load as much tonnage of incendiaries as possible -- mainly the M69, a 225-kilogram cluster of napalm bomblets engineered to ignite a wide rash of 500 ℃ fires. Wooden houses and shops were reduced to ashes, and from interviews on record we know that the smell of burning flesh reached even the pilots.

"Looking up, we couldn't believe it," Michiko Kiyooka recalls of the first minutes of the bombing. "B-29s bigger than we'd ever seen, like a swarm of dragonflies, coming one after another. And from their bellies dropped the incendiaries. Flames were already leaping from the second floor of the house across the street." Hours later at dawn, when she emerged from the icy water of the river, she instinctively moved toward a fire on shore to warm herself, only to realize its source was a mass of burning bodies.

|

|

"A means of documenting the past that is as fragile as life itself, paper is a central metaphor of the film," Francis says. We see it in scrolls memorializing the dead, in maps and posters used by survivors in their campaigns, in the reams of signatures painstakingly collected by elderly volunteers, and as the very bureaucracy they fight. Photo by Brett Ludeman |

As Tsukiyama walks us down the street where his family fled, you can only hope that the opportunity to relive the moment is therapy. Around here was the air-raid shelter where there had only been room left for two. He steps away. Right about here were the station pillars where he and his father crouched with others to shield themselves. Over there was their house, now gone. As a whirlpool of fire bore down upon them he watched there as the cart loaded with their only provisions was reduced to scrap metal. Across the street, the shelter housing his mother and sister disappeared from view, engulfed in flames. Unable to breathe or move -- there was no oxygen, the very air itself was on fire -- he watched in paralyzed horror as a small boy huddled with them burned alive. When the firestorm passed, he and his father crossed the street to the shelter, now reduced to columns of purple and white smoke.

|

|

"The line between living and dying was paper-thin," says Kiyooka, looking out over the Sumida River on Kototoi Bridge. Photo by Brett Ludeman |

Over the two-year shooting period, the survivors invited Francis and his crew into their homes, their lives, their most painful memories. We see them as they pursue various campaigns: petitioning the Diet for the release of archival materials and records, for a dedicated memorial, compensation, a museum. As they vent frustration at repeatedly receiving no audience from elected officials. And as they meet with survivors of Japan's firebombings of Chongqing, China, affirming that "as victims of war we must unite to deter it." We see their outrage that Curtis LeMay, the U.S. general behind the Japan firebombings, was decorated by the Japanese government in 1964 with the Order of the Rising Sun for his role in establishing the country's postwar Air Self-Defense Force. "With that, Japan effectively stated that the U.S. firebombing is a non-issue," a survivor says, despairing. Most of all, we see these octogenarians and nonagenarians express concern about their own limited time left, and how to reach those who will carry on their pleas for peace when they are gone.

|

|

Names of Morishita 5-chome residents who perished in the raid are reflected in Tsukiyama's glasses. "Attending our district's memorial service each year is, for me, like visiting my family's graves. And it's a chance to pray for peace." Photo by Brett Ludeman |

Despite the candor Paper City captures, in general survivors' stories were slow in coming. "As a defeated Japan began to rebuild, the nation looked firmly to the future, rather than deal with the complex mix of guilt, shame, and complicity of its war memories," Francis offers. Only in the 1960s, driven in part by the widespread dissent of the times, and certainly by the images of a carpet-bombed Vietnam flashing across their television screens, did people who lived through the hellfire begin to open up -- writing, speaking, and painting their experiences, and tracking down the documents and other materials necessary to revisit and reassess the scale of the destruction. "For some," Francis says, "this was the beginning of their political awakening. They knew a painful truth -- that if it were not for their own government's aggressions, Japanese cities would never have been bombed."

Hoshino began petitioning the national government for the proper recording of names in 1995, 50 years after the war's end. "The truth is the truth, no matter how many years pass," he says. "The target was not war plants and other factories but the houses and dormitories of civilians. All of this is laid out in the directives. They are inhumane, savage tactics. If you target towns and cities, there will be civilian casualties. It's happening in the Middle East now. So we work to bring it to light. The loss of lives, homes, property -- responsibility lies with the state."

|

|

"Any character is shaped by a long human history of feelings, conditions, and sensations both visible and invisible," says calligraphy artist Edo. Her brushwork brings an immediate sense of place to Paper City. Photo by Max Golomidov |

Extreme close-ups of Hiromi Edo's inked brush on washi paper create a topography that is intimate and infused with memory, like the survivors' tales we cannot see. A single drop of red ink might fall to the page, its circle growing wider as it hits. Or the brush might trace a black line that stops abruptly as a survivor retells a scene in his mind's eye: becoming separated from a brother who would never be seen again. "A stroke of ink might evoke the curve of the Sumida River," Francis explains, "or the spread of fire itself." Lines may crisscross back and forth at different angles, making a tangled mess.

If you live in Tokyo, you probably encounter someone 78 years or older often in the course of a week: a fellow shopper at the grocery store, a person in line at the bank or post office, a passenger on a bus. Consider that this individual likely carries a living memory of horrors none of us wants repeated. We need to remember this, too, when we hear news about attempts by Japan's current administration to revise the pacifist Article 9 of the constitution, enabling the expansion of the Self-Defense Forces' operations overseas. "Unless you hear different people's stories of their experience," a survivor says in the film, "you can't really know what war is."

Francis is now working on a rough cut of Paper City, ordering scenes and adjusting sequences for continuity. (The parts described here are from this work-in-progress.) This summer he'll work remotely with an editor in Australia to tease out and strengthen the film's rhythms and structures. The shooting and editing were self-financed; a March crowdfunding campaign raised 60 percent of the 4 million yen needed to bring the film to fine cut. The production team seeks additional funds beyond that to hire a composer and sound designer, color-grade the work, and make a digital master. While documentary film is no substitute for government action, storytelling like this, in the hands of a skilled and empathetic artist like Francis, is one of the most cogent means we have toward effecting a more equitable, just, and humane society.

For more information on the firebombings, see the Japan Air Raids digital archive or visit the The Center of the Tokyo Raids and War Damage, a modest, privately funded research facility and museum in Koto ward. Those who wish to support the production of Paper City can do so by clicking the donate link on the film's website below, or by contacting @papercitytokyo on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter.

All photos are courtesy of Paper City director Adrian Francis. |

|

|

Susan Rogers Chikuba

Susan Rogers Chikuba, a Tokyo-based writer, editor and translator, has been following popular culture, architecture and design in Japan for three decades. She covers the country's travel, art, literary and culinary scenes for domestic and international publications. |

|

|

|