|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Mastering Material and Fashioning Form: Bauhaus Comes to Japan

J.M. Hammond |

|

Bauhaus Building Dessau, by Walter Gropius (1925-6). Photo by Tomoyuki Yanagawa, 2015

|

In the early 20th century, innovation and modernization were reshaping how the world looked no less in the fields of architecture, fine art, and design than in science and industry. Many of the leading developments were taking place in Europe, and the art school known as the Bauhaus, based in Germany, was at the heart of the design revolution. Its influence was widespread, even reaching Japan. A new exhibition at Tokyo Station Gallery surveys the school's output and teaching practices, concluding with a look at the work of four Japanese students of the Bauhaus who returned to work in Japan. Titled come to bauhaus! -- the basis of education in art and design, the show packs in about 300 exhibits.

The school, properly called the Staatliches Bauhaus, was opened in 1919 in Weimar by the architect Walter Gropius. It had two different architect-directors after him, and two more incarnations (in Dessau and then Berlin), before closing in 1933 in the face of pressure by the Nazi regime. The school placed an emphasis on craftsmanship even as the world increasingly embraced mass production.

|

|

|

|

|

Fritz Schreiber, Students on a Balcony at the Prellerhaus, Bauhaus, Dessau (c. 1932). Collection of Misawa Homes Co., Ltd.

|

A number of top-league professional artists were among the teaching staff, and here we can see what these influential figures actually taught by way of sketches, prototypes and other works made by their students. Most are original pieces; some are recent reproductions. The first big room of the exhibition (after some Bauhaus-related brochures, magazines and books) contains nearly a dozen items revealing what students in Paul Klee's classes were getting up to. Particularly telling is a recognizably Klee-like sketch of a human face, the parts of which have been reduced to fundamental shapes of circle and triangle (and square for the body), and another figurative study of a human figure, whose joints are rendered as circles. Both sketches were made in 1923 by a student of Klee at the Bauhaus, Karl-Hermann Haupt.

Taking the abstraction of geometrical form even further was Wassily Kandinsky. Here we have half a dozen analytical drawings, made by students in his class, that reveal the tension that can arise from various combinations of shapes in space.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Joost Schmidt, Poster for the Bauhaus Exhibition in 1923, Collection of Misawa Homes Co., Ltd.

|

|

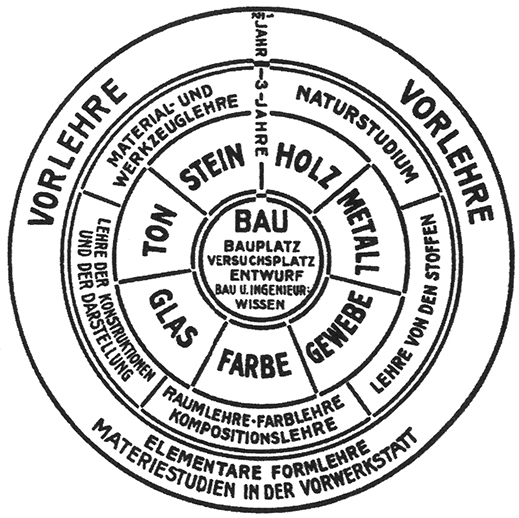

Curriculum of the Bauhaus Weimar, 1922 |

One of the core principles at the Bauhaus was ensuring that each project placed utmost importance on the function of the item being created and the qualities of the material it was being made from. With this in mind, Josef Albers had his students conduct studies using sheets of paper so they could experience the malleability, and potential, of the medium. These "material exercises" could invite some comparison with the Japanese art of origami, especially one that involves students taking a sheet of paper and folding it in such a way as to create rows of pyramid-like ridges. The end result is geometrical in nature as opposed to the animals, flowers and other natural wonders usually produced by origamists, but the approach is similar in the transformation of the flat surface into three dimensions. In several other exercises, students cut along one continuous line without discarding any paper, so as to be able to pull up the strips to create a three-dimensional shape and yet be able to collapse it back into the original flat sheet.

Other Bauhaus items introduced in the show include furniture, kitchen utensils such as coffee and tea pots, graphics, stage designs, and architectural projects. There is even the rare treat of a 30-minute color film, made in 1970, replicating an avant-garde ballet staged in the 1920s by Oskar Schlemmer, who headed the Bauhaus theater workshop.

|

|

Marcel Breuer, Nest Table B9 - B9c (1929). Collection of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo |

The Japanese creators who studied at Bauhaus enter the picture toward the end of the exhibition. Iwao Yamawaki and his wife Michiko were at the Bauhaus school in Dessau from 1930 until 1932. That year Iwao expressed his frustration at developments in Europe in the photomontage Attack on the Bauhaus, showing Nazi boots trampling over the school building. He had already taken up the socially conscious stance of the Bauhaus even before he set up his easel there, as can be seen in his design proposals (under the name Iwao Fujita) for a Theatrical Arts Laboratory to be built at the site of a factory.

Iwao taught architecture and Michiko textile design at the Shin Kenchiku Kogei Gakuin (School of New Architecture and Design), opened in 1932. The school's program was adapted from the preliminary course offered at the Bauhaus and tailored to the needs of Japanese students. The school was the brainchild of the architect, educator, writer and translator Renshichiro Kawakita, and grew out of the journal Kenchiku Kogei. I See All (Architecture and Crafts. I See All) that he launched in 1931, a copy of which is on display here. Kawakita is not featured much in the exhibition, but he did more than perhaps anyone else to spread the ideas of the Bauhaus in Japan despite never visiting Germany itself, or even setting foot outside Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

Exhibition view of replications of "material exercises" created in classes taught by Iwao Yamawaki. Photo by J.M. Hammond

|

It is believed that Iwao Yamawaki had his students at the School of New Architecture and Design conduct "material exercises" similar to those designed by Josef Albers. Some recent reproductions of these, based on photographs in Japanese journals, are included here. Also on display are some textiles -- a scarf and two obi sashes for kimono -- by Tamae Ohno, who enrolled at the Bauhaus in Berlin after studying fashion in Paris. These show how Ohno adapted what she had learned of textile design to the Japanese context -- or you could say they show how she reinvented traditional Japanese textile design by incorporating Bauhaus principles.

Some of the work of the architect Takehiko Mizutani is featured here. Mizutani studied at Dessau from 1927, even earlier than the Yamawakis, and after returning to Japan in 1930 he taught at his alma mater, the Tokyo Fine Arts School. Here we can see how he contributed to architecture journals, including one edition of the influential Shinkenchiku (New Architecture), where he wrote about modern design from Art Nouveau to Bauhaus.

|

|

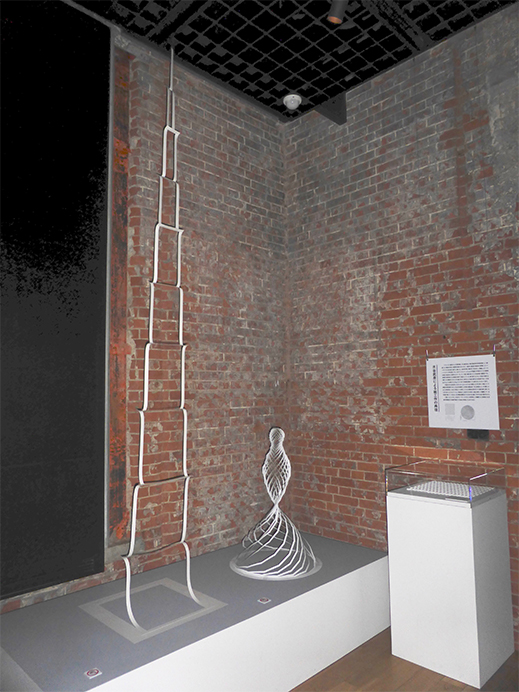

Exhibition view with two works by Takehiko Mizutani, Two Persons (left) and Construction Principle (right). Photo by J.M. Hammond |

One of Mizutani's creations, Construction Principle, shows all the hallmarks of a Bauhaus-inspired abstract form but also reveals a striking resemblance to a traditional Japanese tsuzumi hand drum. Whether this is intentional or purely coincidental is unclear, as there is still relatively little known about the precise design philosophies and principles of Japanese Bauhaus-inspired architects and designers. However, the fact is that alongside the large number of items in the exhibition on loan from Japanese art museums, a huge proportion comes from a leading Japanese house construction company. This would suggest that interest in, and the impact of, the Bauhaus is as alive as ever in today's Japan. Though the Japanese angle is not the main focus of come to bauhaus!, the emphasis on craft and material common to both the Bauhaus and traditional Japanese art and design is implicit here, and merits further teasing out.

Exhibition view of Bauhaus graphics. Photo by J.M. Hammond |

All images are courtesy of Tokyo Station Gallery except those taken by the author. |

|

|

J.M. Hammond

J.M. Hammond researches modernity in Japanese art, photography and cinema, and teaches in Tokyo, including as a faculty lecturer in the English department at Meiji Gakuin University and at Gakushuin University. He has written about art for The Japan Times for over a decade. His essays include "A Sensitivity to Things: Mono No Aware in Late Spring and Equinox Flower" in Ozu International: Essays on the Global Influences of a Japanese Auteur (Bloomsbury, 2015) and "The Collapse of Memory: Tracing Reflexivity in the Work of Daido Moriyama" for The Reflexive Photographer (Museums Etc, 2013) [reprinted in the same publisher's 10 Must Reads: Contemporary Photography (2016)]. He has given various conference papers, including at the University of Hong Kong and the University of Oxford. |

|

|

|