|

|

|

HOME > FOCUS > When Bad Things Happen to Good Artists: Ill-Starred Painters in Arashiyama, Kyoto |

|

|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

When Bad Things Happen to Good Artists: Ill-Starred Painters in Arashiyama, Kyoto

Colin Smith |

|

Kiyochika Kobayashi, The Great Hisamatsucho Fire, 1882, portraying an all-too-common occurrence in old Tokyo. |

Some museum-goers skip over explanatory wall panels, whether because of time constraints or because they feel the art ought to speak for itself. If this is you, Ill-Starred Painters is worth making an exception for and ensuring sufficient time to read the accompanying texts. The 130 works in the exhibition, held at two neighboring museums in Arashiyama, Kyoto, range widely in era (early 18th to early 20th century), style, and subject. While some depict tragic scenes, what unites them thematically is the sorrow and adversity that figure in the lives of the artists. Perhaps the prize for agony goes to Tanaka Totsugen (1767-1823), who after losing his eyesight died by biting off his own tongue, but there's no shadow of grief in his adorable Cat Playing with Peacock Feather (1817) -- one of many striking contrasts between trauma in life and tranquility in art that emerge on reading the artist biographies (provided in English) on the walls.

|

|

|

|

|

|

A history of heartbreak: Shoen Uemura's Shizuka Gozen, 1910, and Karujo's Grief of Parting, 1900, are solemn scenes from sweeping sagas. |

In terms of calamity on canvas (or silk, in this case), The Great Hisamatsucho Fire (1882) by Kiyochika Kobayashi (1847-1915) is a show-stopper based on personal experience: the artist lost his home in one of the frequent conflagrations that were known as "the flowers of Edo," as were fights. None of the latter are to be seen in this show, but several sad scenes show the bitter fruits of conflict impacting women. Shoen Uemura (1875-1949), a renowned female Nihonga (modern Japanese-style) painter in a male-dominated art scene, affectingly portrays Shizuka Gozen (1910), whose baby was intentionally drowned in the sea due to Minamoto clan infighting during the 12th-century Genpei War, and Karujo's Grief of Parting (1900), from the tale of the 47 Ronin (masterless samurai). Another poignant parting, in Cai Wenji Returns to Her Homeland (1916) by Kokkan Otake (1885-1945), comes from Chinese history. Cai was captured by northern nomads and had two sons with a chieftain, but had to leave her children when she was freed with a handsome ransom and repatriated to placate ancestral spirits as the last surviving member of her clan.

|

|

A family torn apart in Cai Wenji Returns to Her Homeland, 1916, by Kokkan Otake. |

Sociopolitical turmoil shattering lives is a theme running through many of the artists' biographies, too. Several were exiled after run-ins with the authorities, including Watanabe Kazan (1793-1841), who subsequently defied an order to stop selling paintings during his banishment, got caught, and committed ritual seppuku in penance for embarrassing his lord. He had been censured for covertly criticizing the Shogunate and supporting Western ideas, which appeared in his paintings in the form of European-style shading and stylistic elements. A similar fate awaited Reizei Tamechika (1823-1864), who hid out in Wakayama disguised as a priest (even erecting a fake tombstone in his birth name) -- though he was on the other side of the struggle, and was hunted down and assassinated for perceived disloyalty to the anti-Shogunate movement to restore the Emperor. Yet no tumult is evident in the serene works by these painters. The same can be said for many works on view here, including those of Nagasawa Rosetsu (1754-1799), one of the "Three Eccentrics" of 18th-century Kyoto along with Ito Jakuchu (1716-1800) and Soga Shohaku (1730-1781). Rosetsu led a turbulent life and is believed to have died after being poisoned.

|

|

Nagasawa Rosetsu, Decorative Paper Balls, 1788; Watanabe Kazan, The High Gate of Lord Yu, 1841; and Yumeji Takehisa, Red Kimono, Fan Dance, 1929.

|

Some artists' fates don't seem all that bad. Yumeji Takehisa (1884-1934) gained enduring popularity with the willowy sad-eyed ladies in his modernist take on the bijinga (beautiful women) genre, but according to the wall text his "high workload accelerated his death . . . at the age of only 50." Then again, it was an era when the old saying "Man has but 50 years" still held true on average. The only non-Japanese artist featured, France's Maurice Utrillo (1883-1955), was long-lived and renowned for charming urban landscapes, but battled throughout life with alcoholism and mental illness. In the same gallery, a European scene by Gyoshu Hayami (1894-1935), Deserted City (1931), gives eerie premonitions of the catastrophe that would sweep the continent not long after the artist succumbed to typhoid fever at age 40.

Europe on the eve of war: Maurice Utrillo, Saint Pauline Church of Le Vesinet, 1938, and Gyoshu Hayami, Deserted City, 1931. |

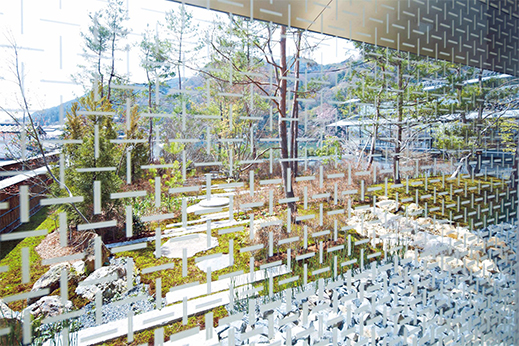

Why dwell on misfortune at a time when we could all use some uplift? For one thing, the show's subtitle at one of its two venues (the Fukuda Art Museum), "Against All Odds," conveys a paradoxically positive message: tragedy highlights the power of artists to overcome adversity and create things that live on after they meet their ends, however bitter. History is full of pandemics as well as warring clans, frequent urban conflagrations, banishment to remote islands, and other events we can be thankful we no longer face. Moreover, the Fukuda Art Museum is itself an uplifting place. Marking its one-year anniversary with this exhibition, it occupies a beautiful Japanese-modern building mere steps from the famous Togetsukyo Bridge in Arashiyama, with glass exterior walls strikingly patterned with a stylized wickerwork design, a garden, and panoramic views of the river, mountains and bridge (visible from the corridors, best seen from the café). The show continues at the Saga Arashiyama Museum of Arts and Culture, just one block upriver, with a different take on the ill-starred theme. Subtitled "Coming Back from Oblivion," it focuses on painters who were stars in their day but are now largely forgotten, such as Shunkyo Yamamoto (1871-1933), who like Kazan incorporated shading and other aspects of Western-style realism into a traditional Japanese idiom.

At the peak of the fall foliage this year, the news reported that visitors to hot spots like Arashiyama were even more numerous than in average years, despite the coronavirus and the absence of overseas tourists. Life goes on, as it did during the historical and personal calamities depicted and described in Ill-Starred Painters. The Fukuda Art Museum is a wonderful refuge from all that, and this exhibition is a fascinating survey of artists from multiple centuries brought together by the universal human experience of hardship.

|

|

Through a glass brightly: Fukuda Art Museum offers lovely views of its garden and the scenery of Arashiyama. |

All images courtesy of Fukuda Art Museum.

|

|

|

Colin Smith

Colin Smith is a translator and writer and a long-term resident of Osaka. His published writing includes the travel guide Getting Around Kyoto and Nara (Tuttle, 2015), and his translations, primarily on Japanese art, have appeared in From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and many museum and gallery publications in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|