|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Hiroshi Yoshida: Scaling the Heights of Expression

J.M. Hammond |

|

The Taj Mahal in the Morning Mist No. 5, India and Southeast Asia (1932)

|

Few artists in Japan -- at least not until recent decades -- have so thoroughly blurred the distinction between Japanese-style and Western-style art as Hiroshi Yoshida, who worked from the Meiji through to the Showa era. At the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, a new exhibition of Yoshida's works, mainly woodblock prints and watercolors, explores his legacy and his unique approach to his art. Yoshida Hiroshi: Commemorating the 70th Anniversary of His Death puts together close to 200 items spanning his entire career.

|

|

|

|

|

Kameido, Twelve Scenes of Tokyo (1927)

|

Yoshida (1876-1950) was born in Fukuoka Prefecture in southwestern Japan, and was adopted at a young age by the artist Kasaburo Yoshida. He moved to Tokyo and studied at various institutions, including the Meiji Fine Arts Society. Western-style art had taken a foothold in Japan just a few decades before then. One leading figure was Seiki Kuroda, who was one of the first Japanese artists to study in Paris -- and many more were to follow in his wake.

In 1899, Yoshida, still in his early twenties, also headed for Europe, but only after a lengthy stay in the United States, a somewhat unusual choice for a Japanese artist at that time. This choice of destination speaks to his rebellious spirit -- he wanted to differentiate himself from the love affair with France championed by Kuroda -- but it also proved pivotal to his career. His watercolors sold well in Detroit, and in the years that followed he took part in two joint exhibitions with another Japanese artist in that and other cities. He also saw the passion American buyers had for ukiyo-e prints, and as a result took up woodblock printmaking -- although not immediately -- with an eye on this market.

The exhibition opens with several early watercolor works that display Yoshida's sense of subdued coloration and his softness of touch. We can also see an impressive oil painting titled Rapids from 1910, complete with heavily textured rocks and frothy flowing water.

|

|

Rapids (1910), oil on canvas, courtesy of the Fukuoka Art Museum

|

In 1928, Yoshida seemingly revisited this scene as a woodblock print, re-imaging the softly textured falling water of the original through expressive line work. His first attempts in this medium took place in the years between 1920 and 1922, as can be seen in Afternoon in a Pasture from 1921. This depicts cows grazing and highlights how the artist harnessed bold, almost manga-like lines to convey a strong sense of form.

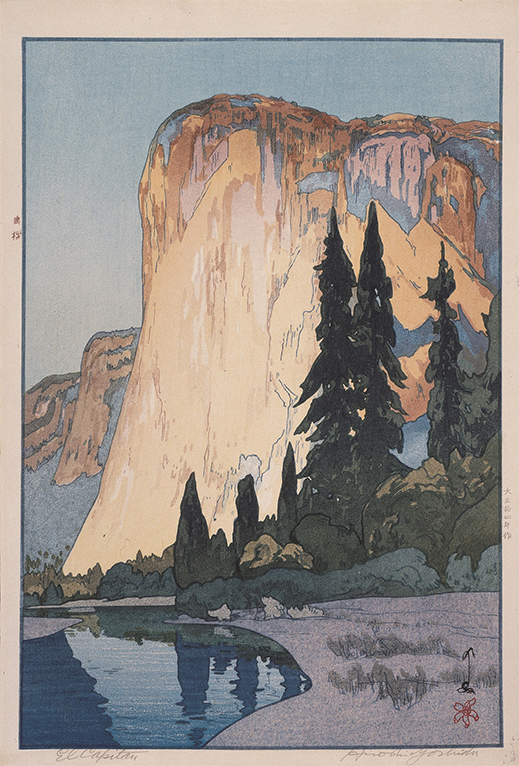

From 1925, he began concentrating on woodblock prints. This shift served as a second wind for the artist, who was 49 at the time. With the American audience in mind, he launched his United States series that year, depicting famous landmarks like the Grand Canyon and Yosemite National Park's El Capitan in what could be considered a "Japanese" style.

|

|

|

|

|

El Capitan, The United States Series (1925)

|

A work such as Niagara has a passing resemblance to certain works by ukiyo-e artists like Hiroshige, but is less stylized. More muted in coloring, and more naturalistic in feel, Yoshida's prints are in line with the burgeoning shin-hanga movement of the day, which aimed to elevate woodblock prints as an art form. Like other shin-hanga artists, Yoshida often took control of every aspect of production, including the actual printing of the woodcuts, instead of leaving that task to the printer or publisher, as was the case in the past.

His U.S.-themed works were soon followed in the same year by a Europe series, where he similarly turned his attention to depicting the continent's cultural heritage as well as its natural beauty. Alongside various views of the Alps, Yoshida portrayed sights like the Acropolis and the Venetian canals.

Sunrise, Ten Views of Fuji (1926)

|

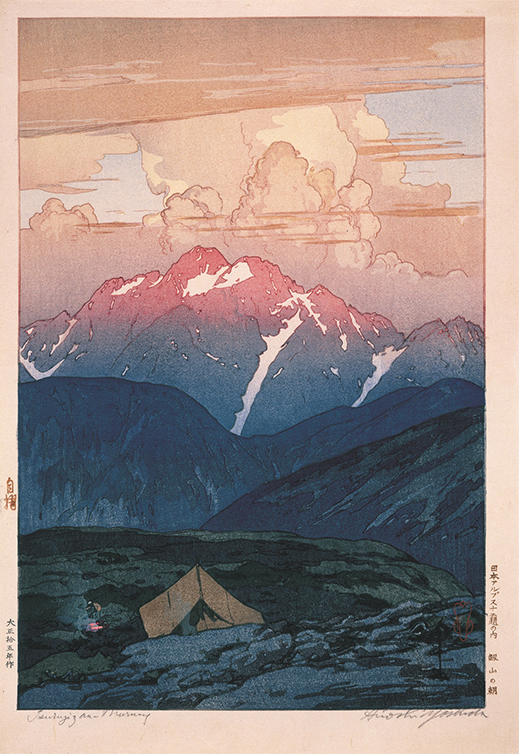

Yoshida also travelled extensively around Japan and was a keen hiker, often spending weeks on end, sketchbook in hand, up various mountains, including Mount Fuji. Like Hokusai before him he portrays this iconic peak from various vantage points, often with another element of interest in the foreground -- be it a lake, a mountain village, or the plains of Musashino.

Yoshida was a master of depicting different light conditions in his woodblock prints, and one of his techniques was to use the same woodcut block to show the same scene in different colors and moods according to the time of day.

Sailing Boats - Afternoon (left) and Sailing Boats - Evening (right), The Inland Sea Series (1926)

|

His scenes of sailing boats on Japan's Seto Inland Sea, from 1926, have long been popular (Princess Diana of the U.K. hung one on her wall). Here we can see the same view in the clear blue light of the afternoon and also through a veil of pink as the sun sets in the evening. Other prints in the series feature the scene at night or in the glow of early morning light. The atmospheric shrouds of light and color that enwrap Yoshida's images are in many ways closer to the translucent quality of watercolors than to traditional Japanese woodblock prints, highlighting the difficulty of attempting to place Yoshida as either a Western-style or Japanese-style artist (he has been described as both).

|

|

|

|

|

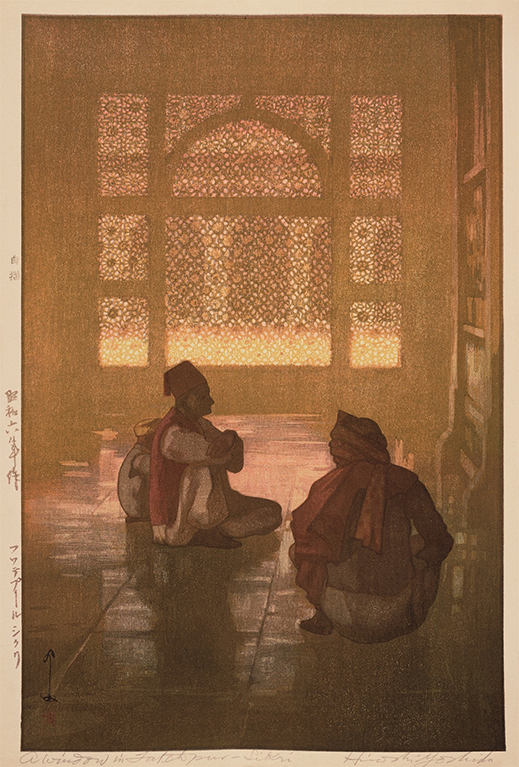

Fatehpur Sikri, India and Southeast Asia (1931)

|

This sensitivity to light is also on full display in Yoshida's India and Southeast Asia series, as in Fatehpur Sikri -- an evocative portrayal of two figures crouching in the diffused golden rays of sun filtering through a mosque. Yoshida traveled with his son through Southeast Asia to India from late 1930 into the spring of the following year. After he returned to Japan, he turned his numerous sketches into the 32 prints that make up this series.

Through photographs of the artist and the sketches he made on his various travels, the exhibition succeeds in also providing a glimpse into Yoshida's character and personal life. During the Second World War, he was recruited as a war artist and sent to China, although his work from this period is not on display here. In the years after the war, as his strength declined, Yoshida made fewer woodcuts and worked more in oils and watercolors again.

No matter the medium or style Yoshida worked in, he made it his own. Yoshida Hiroshi: Commemorating the 70th Anniversary of His Death shows us the heights of expression that this unique artist scaled in his lifetime.

|

|

Morning on Tsurugisan, Twelve Scenes in the Japan Alps (1926) |

All works pictured are woodcuts on paper by Hiroshi Yoshida, images courtesy of the Yoshida Hiroshi Exhibition, except where otherwise noted. |

|

|

J.M. Hammond

J.M. Hammond researches modernity in Japanese art, photography and cinema, and teaches in Tokyo, including as a faculty lecturer in the English department at Meiji Gakuin University and at Gakushuin University. He has written about art for The Japan Times for over a decade. His essays include "A Sensitivity to Things: Mono No Aware in Late Spring and Equinox Flower" in Ozu International: Essays on the Global Influences of a Japanese Auteur (Bloomsbury, 2015) and "The Collapse of Memory: Tracing Reflexivity in the Work of Daido Moriyama" for The Reflexive Photographer (Museums Etc, 2013) [reprinted in the same publisher's 10 Must Reads: Contemporary Photography (2016)]. He has given various conference papers, including at the University of Hong Kong and the University of Oxford. |

|

|

|