|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

The Shape of Things Gone By: A Career-Spanning Exhibition of Miyako Ishiuchi

Colin Smith |

|

Miyako Ishiuchi, Hiroshima #71, 2007, and Hiroshima #131, 2020. The artist has called this ongoing project at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum her life's work.

|

The internationally renowned photographer Miyako Ishiuchi can be called a portraitist, though people's faces rarely appear in her work. She is known for evoking people through things, and while a conventional portrait erects barriers between photographer and subject, seer and seen, she breaks them down by viscerally capturing the textures of objects and places and connecting us to their former owners and occupants. This works to powerful effect in her well-known series ひろしま/hiroshima, Frida by Ishiuchi, Frida Love and Pain, and Mother's, all close-ups of clothing and personal, often intimate items that once touched skin. Skin itself is the subject of two other series, Scars and Innocence, which sensitively portray the surfaces of bodies affected by injuries, illnesses, and inexorable time.

Miyako Ishiuchi, Frida Love and Pain, 2012. The Museo Frida Kahlo commissioned Ishiuchi to photograph Kahlo's possessions at its archive in Mexico City.

|

Besides the human presence, time is Ishiuchi's main subject, and the title of her first large-scale exhibition in the Kansai region, Ishiuchi Miyako: Seen and Unseen -- Tracing Photography at the Otani Memorial Art Museum, Nishinomiya City (Hyogo Prefecture), speaks to her dedication to rendering that unseen fourth dimension visible. In a conversation at the museum with the novelist Yoko Ogawa, Ishiuchi remarked, "We can't see, touch, or smell time. It's as far removed from our senses as could be. But I thought I might be able to photograph it." Crucially, she achieves this in images that are poignant without being sentimental or sensational -- no easy feat when the subjects are garments worn by victims of the Hiroshima atomic bombing, personal effects of the severely injured painter Frida Kahlo (including a gaily decorated medical corset and prosthesis), old undergarments and lipsticks recovered after her mother's death, or scenes of deserted former red-light districts.

|

|

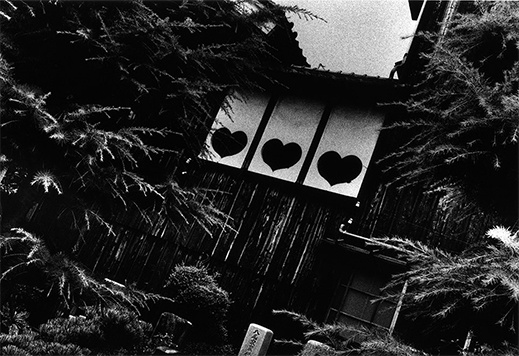

Miyako Ishiuchi, Endless Night #2: Tosenji (Yamato-Koriyama City, Nara), 1978-80. Ishiuchi traveled all over Japan photographing former red-light districts, and continues to add to the series.

|

These last date from 1978-1980 and are the earliest works in a more or less comprehensive retrospective. Fifty of the 170 prints in the show plus a slideshow of newer works are from this series, Endless Night, which documents decrepit building exteriors and interiors in historic red-light districts throughout Japan. Shot in her early grainy, high-contrast monochromatic style, they convey pathos with tawdry details like heart-shaped windows and cheap stained glass, while the cumulative effect of an endless procession of images lets the viewer imagine the numbing sameness of nights in these establishments.

Miyako Ishiuchi, INNOCENCE #77, 2006, and saEboEten #3, 2013. The dramatic juxtaposition of works in the exhibition's third section is a brilliant curatorial move.

|

The exhibition is in four parts, demarcated by differently colored walls but not arranged chronologically or assigned themes. This is an excellent curatorial decision, as is the revelatory intermingling of multiple series in the third section. Ishiuchi works in series, and her photographs benefit from being grouped accordingly, but the third gallery uncharacteristically intersperses black-and-white prints from Scars and Innocence with vivid color close-ups of alien-looking cacti and wilting roses, heightening the startling effects of both sets of images. Scarred flesh appears beautiful, reflecting Ishiuchi's observation that "scars are proof of life, saying 'I survived this,'" while roses defy clichéd expectations of beauty as their petals grow withered and discolored. The bizarre and bulbous forms of cacti show the tenacity of life under harsh circumstances.

|

|

|

|

|

Miyako Ishiuchi, Frida by Ishiuchi #36, 2012. The image speaks volumes about the Mexican painter's agonies and zest for life.

|

Among her most famous series, ひろしま/hiroshima is an annual project ongoing since 2007 in which Ishiuchi mounts clothing and accessories worn by bombing victims, from the collection of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, on a large light table and shoots them in color. She notes that photographs in textbooks give the impression that people lived in black and white and wore only drab work-wear during the war, and she felt compelled to show the vivid colors and cute, stylish designs many actually wore, remarking on one, "That gingham check dress is something I might have worn myself." The result is striking immediacy and empathy with people of 76 years ago, and the polka dots and hand-stitching win out over the holes, burns and stains to affirm the wearers as relatable individuals, not anonymous victims. The undergarments, shoes, handbags and crumbling, much-used lipsticks in Mother's (a standout at the Venice Biennale in 2005), and the sometimes festive, sometimes grim possessions of Frida Kahlo, similarly convey the subjects' humanity through their absence in a way no conventional portrait could.

|

|

Miyako Ishiuchi, Silken Dreams #27: Hogushi Kasuri Meisen, Kiryu, 2011. Interest in the graphic as well as the emotive power of textiles goes back to the artist's youth. |

Textiles have been a lifelong concern. Ishiuchi was born in Kiryu in Gunma Prefecture, a major silk-producing region, and studied textile design at Tama Art University (as a photographer she is largely self-taught). Another series, Silken Dreams, focuses on silk itself and the larvae that produce it. As with the cacti and roses, dramatic close-ups of organic substances have a compellingly tactile effect.

Miyako Ishiuchi, Moving Away #23, 2017. Ishiuchi's farewell documentation of her longtime Yokohama home/studio and neighborhood is a glimpse into her everyday life.

|

The fourth and final section is both the most casual and the most personally revealing. One Days and Yokohama Days, from the 2000s, feature everyday scenes in and around the artist's home and studio, "taken without the objective of 'taking photographs.'" In 2018 she left her home and studio of over 40 years in Yokohama and returned to Kiryu; in advance of this she documented herself (mostly hands and feet, with one selfie in a traffic mirror) and her possessions in these familiar surroundings. But last year she was back in Kanagawa Prefecture, where Typhoon Hagibis (No. 19 of 2019) had critically damaged many of her works in a warehouse of the Kawasaki City Museum. The physicality of film and the printing process have always been of vital importance to her, and unique prints -- including those from her Kimura Ihei Award-winning breakthrough series Apartment -- were mold-infested and irretrievable. Overcoming the initial shock, she decided to photograph the ravaged photographs for the series The Drowned, unflinchingly gazing on the fragility and inevitable decay and death of photographs as she has done with people's bodies and belongings.

|

|

Miyako Ishiuchi, The Drowned #2, 2020. The seemingly abstract image is a photograph of a photograph, one of Ishiuchi's own after damage in a typhoon. |

Why hold a retrospective of a living, working artist? In a review of this exhibition in the Japanese edition of Artscape, critic Megumi Takashima writes that such a retrospective "presents an artist's core in concentrated form, while at the same time showing new territory they are now exploring." Ishiuchi told the Mainichi newspaper, which reported on her conversation with Ogawa, "I feel that with this exhibition, I'm getting back to the basics of photography for the first time." The show not only traces the arc of her career thus far, but also hints intriguingly at the shape of things to come.

All images courtesy of the Otani Memorial Art Museum, Nishinomiya City. |

|

|

Colin Smith

Colin Smith is a translator and writer and a long-term resident of Osaka. His published writing includes the travel guide Getting Around Kyoto and Nara (Tuttle, 2015), and his translations, primarily on Japanese art, have appeared in From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and many museum and gallery publications in Japan. |

|

|

|