|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

"Video Is Victory of Vagina": The Radical Art of Shigeko Kubota

Christopher Stephens |

|

River (1981). Photo by Peter Moore. Courtesy of Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation

|

Viva Video!: The Art and Life of Shigeko Kubota, a traveling exhibition on view at the National Museum of Art, Osaka until 23 September, traces Shigeko Kubota's personal and professional journey through a host of photographs, documents, drawings, and videos in the first major retrospective of the groundbreaking female artist's career to be held in Japan in some 30 years.

After briefly trying to make a name for herself in Tokyo, the Niigata-born Kubota (1937-2015) decided that her only hope for success as an artist was to relocate to New York. She arrived in the city on July 4, 1964. Once there, she was invited by George Maciunas, the leader of the experimental art community Fluxus, with whom Kubota had corresponded, to stay in one of the cooperatives he had developed for artists in the neighborhood that would later come to be known as SoHo. Kubota quickly emerged as a key figure in Fluxus and a close confidant of Maciunas, who dubbed her "vice president" of the group. Among Kubota's most notable works of the era is a 1965 performance titled Vagina Painting. In this seminal feminist piece, Kubota attached a brush to her underwear, dipped it in a can of red paint, and smeared the pigment across a large sheet of paper on the floor. Calling up images of menstrual blood, the work was widely seen as a rejection of macho action painting and the male-dominated art world as a whole.

|

|

Duchampiana: Bicycle Wheel One, Two, Three, with Three Mountains in the background (installation view at Hara Museum of Contemporary Art, 1992).

Photo by Yoshitaka Uchida. Courtesy of Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation

|

Nineteen sixty-four was also the year that Nam June Paik (1932-2006) came to New York. Born in Seoul, Paik had fled to Japan with his family following the outbreak of the Korean War. After graduating from the University of Tokyo in 1956, Paik moved to Germany to study contemporary music. During his stay he met the composers Karlheinz Stockhausen and John Cage, and became involved with Fluxus after a 1961 encounter with Maciunas. In 1963 Paik presented his first solo exhibition, Exposition of Music -- Electronic Television, at a German gallery. Filled with prepared pianos, sound objects, and modified TVs (including some that allowed viewers to create images on the screen with a pedal or microphone), the show signaled the arrival of a new genre.

Kubota had already met Paik at a performance he gave at the Sogetsu Art Center in Tokyo. After reuniting in New York, the two began living together in the seventies. They married in 1977, and their lives and work remained closely intertwined until Paik's death in 2006. At the same time, Kubota's efforts were often overshadowed by Paik, whose name had become synonymous with the title "Father of Video Art." In later years, Kubota expressed her frustration with this imbalance by saying, "Even when I did my own stuff, people said, 'She imitates Nam June.' I found it infuriating. So I headed further in the direction of Duchamp. When Nam June went populist, I went for high art."

Sony's introduction of the Portapak, the first compact video-recording system, in 1967, made it possible for anyone, man or woman, to immediately capture images and sound. Weighing five kilograms and retailing for US$1,250 (equivalent to roughly $10,000 today), the battery-powered DV-2400 Video Rover offered a maximum recording time of 20 minutes. Playback, however, was not an option -- only a detachable hand crank was provided to rewind the tape. The technology was a godsend to artists and activists alike. As Kubota explained, "Film was chemical, but video was more organic. To me, Portapak was like a new paintbrush. It was certainly in the same spirit as Fluxus, 'do it yourself.'"

|

|

|

|

|

Duchampiana: Video Chess (1968-75). Collection of Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation (installation view at the National Museum of Art, Osaka, 2021). Photo by Kazuo Fukunaga

|

Kubota originally trained as a sculptor at the Tokyo University of Education (now the University of Tsukuba), and continued working in the medium until she crossed paths with avant-garde musicians and artists like Group Ongaku and Hi-Red Center in 1963. Then, after embracing video in the early 1970s, she combined moving images with frozen forms to create what she called "video sculptures." These include the Duchampiana series (1975-1990) which, as the title suggests, is an homage to Marcel Duchamp. One of the pieces, Duchampiana: Video Chess (1968-1975), consists of a TV embedded face-up in a wooden box, with a transparent chessboard and transparent chess pieces affixed to the screen. Among the electronically processed images (derived from Kubota's own photographs and video footage) that appear on the monitor are scenes from a 1968 chess match between Duchamp, who died several months later, and John Cage. Using a specially wired board, the players triggered or disrupted sounds made by a group of musicians, David Tudor and Gordon Mumma among them, whenever they moved a piece in a series of Cage's trademark "chance operations."

|

|

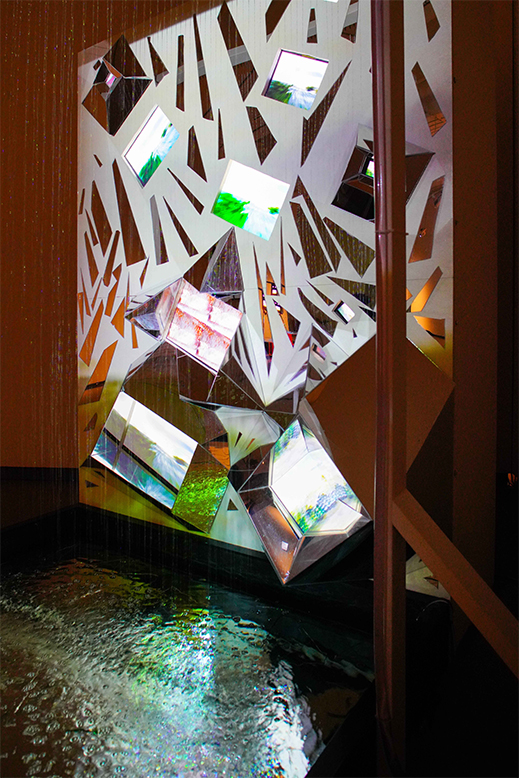

Niagara Falls (1985/2021). Collection of Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation (installation view at the Niigata Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, 2021). Photo by Yukihiro Yoshihara

|

Also part of the series is Duchampiana: Bicycle Wheel One, Two, Three, a work inspired by Duchamp's Bicycle Wheel (1913), in which he affixed a bicycle wheel to the seat of a stool. Kubota's piece consists of three stools with motorized wheels, and small TVs attached to the spokes. Displaying images of mountain landscapes, the spinning monitors carry the viewer off to distant climes.

Natural scenery is a common motif in Kubota's videos, as seen in works like River (1981) and Niagara Falls (1985/2021). The former consists of a curved steel basin fitted with a wave machine. Fragments of mirrors are scattered across the bottom of the receptacle, reflecting images from three monitors that are suspended screen-down over the basin to create streams of lilting color. Niagara Falls, meanwhile, is a large upright wooden structure housing ten monitors, each angled differently, with some set back at the end of a mirror-lined recess. Shards of mirrors also cover the face of the structure, which towers above a reflecting pool as water showers down into it, and moving images of the famous falls dance across the liquid surface.

|

|

|

|

|

Korean Grave (1993). Collection of Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation (installation view at the Niigata Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, 2021). Photo by Yukihiro Yoshihara

|

Kubota's early videos tend toward the diaristic. Some depict Maciunas, Paik, and other Fluxus members milling around in the street and talking, while others, such as Broken Diary: My Father (1973/1975), deal with highly personal themes -- in this case, the death of Kubota's father. The video combines an interview Kubota conducted with her father as he watched TV with scenes in which the artist cries and mourns his death while watching the same images of him on a monitor. Even Kubota's later video sculptures, like Korean Grave (1993), blend private memory with creative expression. A large dome, the work recalls a traditional Korean burial mound, studded with flared cubes and other geometric enclosures that contain monitors of various sizes. Abstract images in an array of colors glide over the walls and ceiling, as light projections bounce off the mirrored surface of the dome. The video documents Paik's first return to Korea in over 30 years, showing him meeting relatives and passing through a U.S. military base to gain access to an ancestral grave. The work is both Kubota's tribute to her husband and a historical reckoning with the changes that had occurred in Korea over the years.

Another important aspect of the exhibition is its emphasis on female creators, many of whom were early innovators in performance and video art. Alongside Kubota's works are those by friends and collaborators such as Mieko Shiomi (who flew to New York with Kubota in 1964), Yoko Ono, and Carolee Schneemann. The standout, however, is Mary Lucier's Polaroid Image Series: Shigeko (1970/2006), a sequence of slides derived from a single Polaroid of Kubota sitting in a chair with her hand on her chin. With each successive image the picture quality degenerates, to the point where only a black screen with a scattering of small dots remains. The work is based on and accompanied by I Am Sitting in a Room, a 1969 sound piece by Alvin Lucier (who at the time was married to Mary), in which he records himself explaining the compositional process, and then plays back the description repeatedly until his speech becomes utterly unintelligible.

Shigeko Kubota's work is endlessly inventive, and her vision is unlike that of any other artist. Her decision to leave Japan and spend the rest of her life in New York was no doubt the right one. But even then, it has taken far too long for Kubota to be recognized. This was perhaps in part due to her uncompromising stance as an artist and a woman -- an attitude that is neatly summed up by the following poem that appears on the wall next to her 1975 piece Video Poem:

Video is Vengeance of Vagina.

Video is Victory of Vagina.

Video is Venereal Disease of Intellectuals.

Video is Vacant Apartment.

Video is Vacation of art.

Viva Videoc

All images © Estate of Shigeko Kubota |

|

|

Christopher Stephens

Christopher Stephens has lived in the Kansai region for over 25 years. In addition to appearing in numerous catalogues for museums and art events throughout Japan, his translations on art and architecture have accompanied exhibitions in Spain, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, South Korea, and the U.S. His recent published work includes From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and Gutai: Splendid Playground (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2013). |

|

|

|