|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Shapes of Things: The Design of Toshiyuki Kita

Christopher Stephens |

|

The "Wink" armchair (1980) can be quickly modified to fit the user's needs. (Photo: Mario Carrieri) |

If invisibility is a hallmark of good design, anonymity is a given for a good designer. Long revered in the design world but largely unknown to the general public, the product and furniture designer Toshiyuki Kita is a perfect example. A retrospective of Kita's over-50-year career, titled Toshiyuki Kita: Timeless Future (running through 5 December at the Otani Memorial Art Museum, Nishinomiya City in Hyogo Prefecture), illustrates how a designer's insights can quietly seep into our lives and change them forever.

Born in Osaka in 1942, Kita worked briefly at an aluminum manufacturer in the mid-'60s before moving to Milan in 1969 and launching his own design firm. Since then, Kita has split his time between Italy and Japan, developing a slew of award-winning works that have become permanent fixtures in the Museum of Modern Art in New York and other museum collections around the world.

Kita first achieved recognition for the "Wink" armchair, marketed by the Italian furniture maker Cassina in 1980. Made of foam-covered steel tubing and finished with easily replaceable pieces of colored fabric, the ergonomically correct chair sits directly on the floor like the legless chairs used with low tables in Japanese houses. Versatility is what makes Wink different. When the base is folded under the seat, resembling a person with their legs tucked beneath their body, the chair provides the user with more height and back support. When unfolded, the base acts as a leg rest, and the knobs on either side of the chair can be used to adjust the head rest (made up of two independently moving pieces) and the back, enabling the user to lie nearly flat in a form-fitting chaise lounge. Soft and bright, Kita's iconic chair is still in production.

|

|

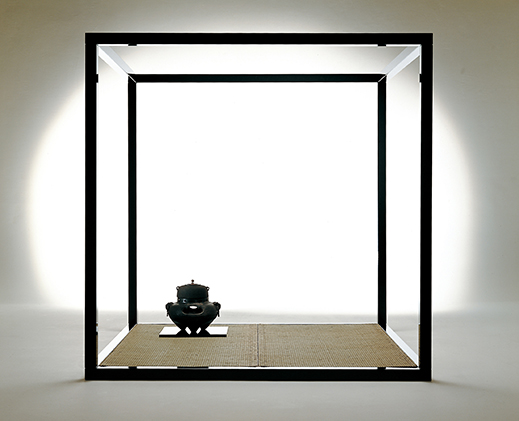

Evocative of a traditional tea room, Ceremony Space (1986) creates an island of calm inside a house or office. (Photo: Yoshio Shiratori) |

In 1986, at the height of Japan's bubble economy, Kita devised an antidote to the rampant materialism of the era called Ceremony Space. So simple as to be almost invisible, the 1.8-meter cube, made of black lacquered wood, frames a two-tatami-mat floor. The power of the construction is hard to fathom from the outside, but once inside, your immediate surroundings fall away, leaving you alone with your thoughts. Recalling a Japanese tea-ceremony room, the enclosure was Kita's attempt to reconnect with the country's spiritual past.

Kita first drew inspiration from traditional Japanese design in the early 1970s with a series of minimal lights. "Tako" (the Japanese word for "kite") consists of a sheet of washi paper hanging a few centimeters in front of a wall-mounted light source. The paper abstracts the shape of the bulb and softens its brightness, filling the space with an atmospheric glow. Kita's fondness for materials like washi, recycled bamboo, and aquatic plants reflects his early interest in sustainability and the effective use of natural resources.

|

|

The "Tako" wall light (1971) was one of Kita's first experiments with traditional Japanese materials. (Photo: Shinya Yamaguchi) |

But this is not to suggest that Kita's concerns lie primarily in the past. Among his most notable designs are those for the Sharp Corporation's Aquos line of flat-screen TVs, including the C1 series of liquid-crystal monitors, which were introduced in 2001. With its toy-like appearance, the 20-inch model announced a shift away from the bulk and brawn of cathode-ray sets to a sleek and stylish form that was perfect for a kitchen counter or nightstand. Easily mistaken for an all-in-one desktop computer, the silver Aquos, distinguished by a gently arching bottom with rounded corners, is mounted on a boomerang-shaped base. The controls are embedded at a slant on the front panel beneath the screen between two slightly bulging speakers. To make the screen viewable from any angle, it can be pivoted from side to side or tilted up and down as needed.

The lightweight Aquos-C1 TV (2001) boasts an adjustable viewing angle while adding style to the décor. (Photo: Luigi Sciuccati) |

Kita moved further into the future with "Wakamaru" (the boyhood name of the 12th-century samurai hero Minamoto no Yoshitsune), a robot he designed for Mitsubishi Heavy Industries in 2003. With a height of 100 centimeters and a weight of 30 kilograms, the bright yellow robot has two highly manipulable silver arms, and gets around by means of a wheel inside its round base. Wakamaru recognizes voices and faces, makes eye contact and shakes hands, and helps out with the vacuuming and other chores. The gender-neutral figure has large droopy black eyes and a duck-like helmet head, giving it a friendly if somewhat forlorn look. Originally intended as a domestic assistant for the elderly, Wakamaru can also detect potentially dangerous situations like fires and medical emergencies.

|

|

The domestic robot "Wakamaru" (2003) helps out around the house and offers a kind word and a handshake. (Photo: Luigi Sciuccati)

|

Throughout his career, Kita has dedicated himself to addressing urgent issues such as the need for renewable energy and reusable materials while simultaneously striving to make our lives more enjoyable and fulfilling. Designs that might have seemed a touch outrageous 50 years ago today appear perfectly attuned to the times, proof that Kita's vision is at once endearing and enduring.

All photos provided by the Otani Memorial Art Museum, Nishinomiya City.

|

|

|

Christopher Stephens

Christopher Stephens has lived in the Kansai region for over 25 years. In addition to appearing in numerous catalogues for museums and art events throughout Japan, his translations on art and architecture have accompanied exhibitions in Spain, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, South Korea, and the U.S. His recent published work includes From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and Gutai: Splendid Playground (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2013).

|

|

|

|