|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Just Passing Through: The Existential World of Saburo Murakami

Colin Smith |

|

Saburo Murakami, Work, 1957. Designed to gradually flake away until the paint is gone, it is still a work in progress. |

Saburo Murakami (1925-1996), a key member of the Gutai Art Association (usually known simply as Gutai), was a regular at Bar Metamorphose, a hole-in-the-wall establishment in the city of Nishinomiya between Osaka and Kobe. The proprietor, Tatsunori Sakaide, wrote an account of experiences with his philosophical and eccentric customer, Two and a Half Drops of Bitters. The title refers to the impossible instructions Murakami gave Sakaide for mixing his drink on the artist's first visit, during which he also praised the bar's layout: "You can come in through one door and go out another on the opposite side . . . a stroke of genius!" The concept of "passing through" was central to Murakami's thought, as well as serving as a title for some of his signature "paper breakthroughs," in which he burst through large sheets of kraft paper (sometimes as many as several dozen in one go) tautly stretched over wooden frames.

|

|

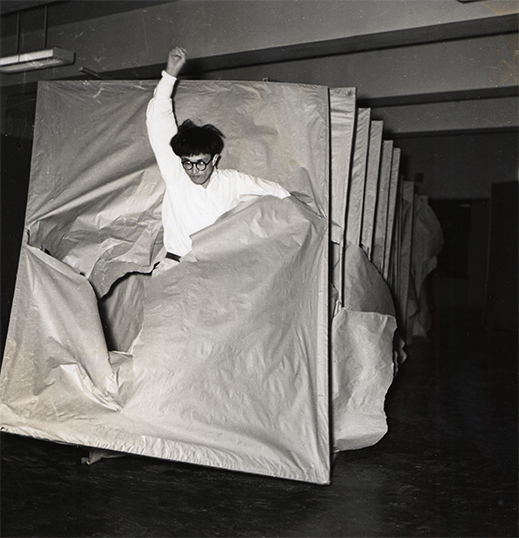

Saburo Murakami, Passing Through, 1956. This iconic photo, from the 2nd Gutai Exhibition, captures the energy of the group's early days. |

Twenty-five years ago, Murakami was scheduled to perform one of these "breakthroughs" on the opening day of his first retrospective, at the Ashiya City Museum of Art & History in the city next to Nishinomiya in Hyogo Prefecture. Sadly, he died during the planning stages, and it became a posthumous exhibition. Murakami Saburo: Unlimited World, now at the same museum, marks both the museum's 30th anniversary and the quarter century since that first exhibition and Murakami's passing. In the first-floor central atrium is a roughly 15-minute video compilation of his performances (primarily paper breakthroughs), staged nearly 40 times from 1956 to 1994 at sites in Japan as well as the Venice Biennale, the Centre Pompidou, and other Western venues. There is a remarkable degree of variation in size, format, number of sheets of paper and degree of resistance, so the act of breaking through ranges from walking nonchalantly through a thinly papered-over building entrance to frantically bashing the paper until he stops, apparently exhausted. There is also an array of archival materials -- newspaper articles, plans, designs, and fragments from past breakthroughs, including the charmingly doodled-upon fusuma room divider his then three-year-old son crashed through when Murakami was holed up pondering a concept for a work, inadvertently providing him with that concept.

|

|

Saburo Murakami, Work, 1963. Even his most gestural abstractions were based on much contemplation and calculation. |

The breakthrough's first iteration was not a performance but a wall-hung work, Six Holes, for which the artist stretched paper over frames, smashed through it and exhibited the aftermath. In fact, Murakami was on balance more a painter and maker of things than a performer, and the current exhibition illuminates this by focusing largely on his 2D works. His 1957 Work (commonly known as Hakuraku suru kaiga, "Flaking-Off Painting") is both an abstraction and a concept piece that conveys his enduring concern with time and its constant companion, change. He applied half-dried black-tinted varnish atop the paint so the black on the surface would flake off gradually, revealing a red layer underneath, and this too would eventually fall away to return the canvas to its original emptiness. On the museum's second floor, two surviving parts of what was once a more than two-by-three-meter painting are on view, and flakes of paint fallen on the bottom edge of the frame show its ongoing evolution.

|

|

|

|

|

Saburo Murakami, Work, 1959. Goodbye to all that: the artist broke with an earlier style by entombing a previous work in a new one.

|

In 1953, Murakami abruptly shifted from somber, European-looking figuration to abstraction with thick impasto slabs of paint. The paint grew thicker, the works grew larger, and after he joined the recently formed Gutai in 1955, they took on the quality of action painting. In his Gutai-era work, gestures are dramatic and drips figure prominently, but there is always a sense of deliberation and restraint, bright colors tempered by neutral tones. Throughout the exhibition, copious notes, sketches and diagrams reveal that works appearing spontaneous, even offhand, are actually products of much careful thought and planning. Paintings with other small canvases attached to their surfaces and painted over are not a gimmick but a declaration of breaking with the past (the smaller canvases were earlier works in what he considered obsolete styles). Throughout Murakami's career there were sudden changes in style and approach, which the exhibition's display of the artist's age at the time of production makes easy to track. Curator Akimi Otsuki says, "It helps viewers understand what was going on with the artist and the historical context, and relate to the artist and the work as they recall themselves at that age -- or envision an age yet to come, as the case may be. Having something in common draws the viewer closer."

|

|

|

|

|

|

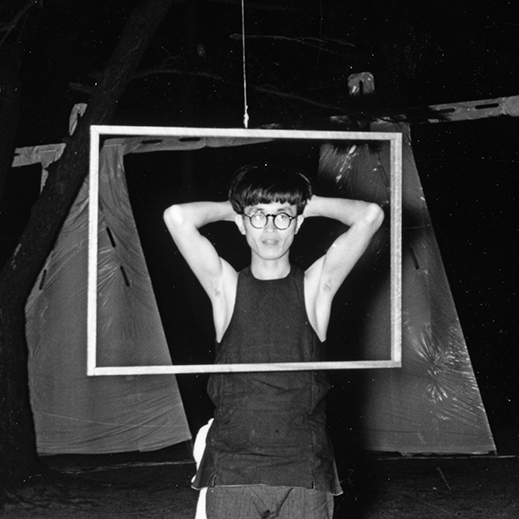

Saburo Murakami, Sky, 1956/1992 (left) and All Possible Landscapes, 1956/1993 (right). Both of these participatory works are portable framing devices. |

|

|

|

|

|

Saburo Murakami, Boxes exhibition, 1971. All but one of the boxes were placed on the Osaka streets with various devices for interaction. Photo by Hideo Natsutani

|

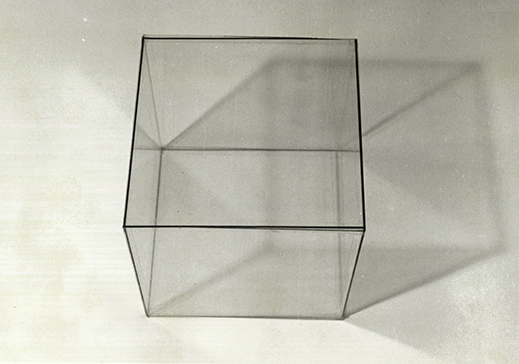

Murakami was quoted in the magazine Fukushoku Techo in 1972: "People's lives are a series of experiences that cannot be communicated. I am interested in making art out of this." In parallel with his painting, he made interactive works that could be called conceptual but are better described as philosophical. Several notable early pieces date from 1956, including Sky, a tall tubular tent topped by a tin cone with a hole in it, placed outdoors (the one on display is a 1992 recreation in the museum's garden). One person at a time goes inside and looks up, capturing their own private circle of sky. Air also deals with capturing, in this case quite literally, the atmosphere of its location inside a 20-cm glass cube. The edition of Box (1971) featured here is a 2001 recreation of one of what were originally 21 large interactive wooden crates with various functions; 20 of these were placed in locations throughout Osaka (a guerrilla action) while one appeared in a gallery. The present-day box contains a hidden clock that can be heard faintly ticking when the ear is nestled against it, and occasionally strikes the hour at inappropriate times. All Possible Landscapes consists of an empty picture frame that transforms whatever is seen through it into art. The 1993 recreation shown here is suspended, slowly twirling, from a wire in the center of a glass-walled room with a view (visitors are invited to give it a spin themselves).

|

|

Saburo Murakami, Air, 1956/1992. This work, too, is intended to be portable and catch the air of the place it is displayed.

|

In the 1970s, Murakami was inspired -- in part by the interactive nature of much of the art at the Gutai Pavilion at Expo '70 Osaka, which he was involved in planning -- to produce works in which he or the audience participated. He moved from framing space to framing time with pieces such as Wooden Clappers (1973), a pair of sticks like those rapped during neighborhood fire-safety patrols, placed inside curtains with instructions that the viewer is to strike them once; Silence (1973), where he was present at the venue but did not speak a word; Water (1974), where each time a visitor arrived he transferred water from a stainless steel bowl to another empty one; and Displeasure by the Principle of Identity (1977), in which visitors wrote their names in a logbook and he immediately crossed them out.

Saburo Murakami, Wooden Clappers, 1973. The artist demonstrates an interactive piece. Photo by Hideo Natsutani

|

Unlimited World also highlights Murakami's lifelong role as an art educator, ranging from a university professorship to a series of engagements at nursery schools. He described children as artistic geniuses, and was committed not to teaching them how to draw or paint, but to drawing and painting together.

"You should know, you're lucky to be alive" was a motto he often shared with fellow customers in his final years, when he was frequenting Bar Metamorphose. Other favorite Murakami sayings quoted in barman Sakaide's book of recollections are amply reflected in this exhibition: "There is no reason for existence." "Get ensnared in yourself." "Performance . . . is survival." Twenty-five years on, Murakami's limit-free world persists.

Murakami and younger artists at Nigawa Nursery School, 1985. Photo by Masataka Shiono

|

All images courtesy of the Ashiya City Museum of Art & History.

|

|

|

Colin Smith

Colin Smith is a translator and writer and a long-term resident of Osaka. His published writing includes the travel guide Getting Around Kyoto and Nara (Tuttle, 2015), and his translations, primarily on Japanese art, have appeared in From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and many museum and gallery publications in Japan.

|

|

|

|