|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Raw Power: The Genius of Art Brut

Christopher Stephens |

|

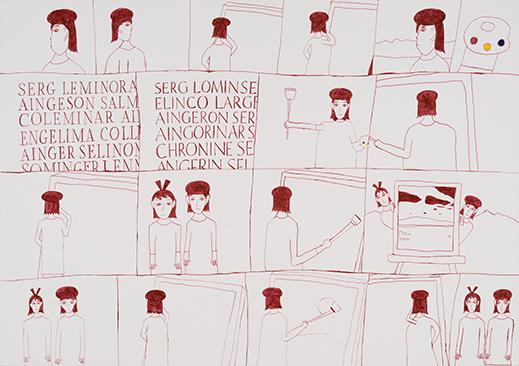

Yuki Fujioka, Untitled (c. 2006-2009), Shiga Museum of Art |

As social norms have changed and art brut (or outsider art) has developed into a viable market, the genre has only grown more controversial, raising knotty questions like, Are the artists working voluntarily or under duress? Are they being properly rewarded for their efforts? Do they conceive of what they make as something to be shown publicly? As the title suggests, Genius: The Human Gift for Creating and Living, an exhibition running through 27 March at the Shiga Museum of Art, celebrates our innate ability to create. And while art brut is its main focus, the show steers clear of absolutes by including Kodai Nakahara, a professional artist whose work is not normally associated with outsider art. The curators also appear to have gone to great lengths to consult with the artists and their families, seeking their approval for the display format and other aspects of the show. In the English translations, at least, they have also drawn a distinction between works that are "untitled" (those that the artist has intentionally avoided giving a name) and "title unknown" (those that the artist has never expressed a view about titling one way or the other).

|

|

Yuki Kamitsuchibashi, title unknown (2020), Atelier Yamanami |

Shiga resident Yuki Kamitsuchibashi's work falls into the latter category. In the first of his three main styles, Kamitsuchibashi (b. 2001) uses calligraphic lettering adorned with swirls to make lists of what appear to be people's names, many of which have similar traits. For example, all of the first names might begin with an A and the family names with a C or an S. At a distance, these lengthy monikers have a vaguely Italian or Eastern European look, but on closer inspection, they are unlike any names you've ever seen: Airegasone Clesmarran or Milgannare Bleddorina. And though they look similar to each other, no two are ever quite the same. In his second mode, powered by his childhood mastery of computers, Kamitsuchibashi designs covers for imaginary books and DVDs. Lettering (primarily alphabetic) lies at the heart of these works as well, and is rendered in a font (shattered, ransom note, etc.) that seems to reflect the content. The words here are just as cryptic as they are in Kamitsuchibashi's calligraphy, but we quickly realize that Selgoridan Lerisartone is the title of a book and that Aindor Lengaco is its author. Kamitsuchibashi's love of DVDs apparently fuels much of his work, and his third style, hand-drawn comic strips, is closer to a series of camera shots than an illustrated narrative. Some of the panels are filled solely with unusual letter combinations, but the words are chopped off by the edges of the panel. The human figures are often static and their faces are devoid of emotion. Talk balloons are nowhere to be found. It is perhaps no coincidence that Kamitsuchibashi himself does not speak.

|

|

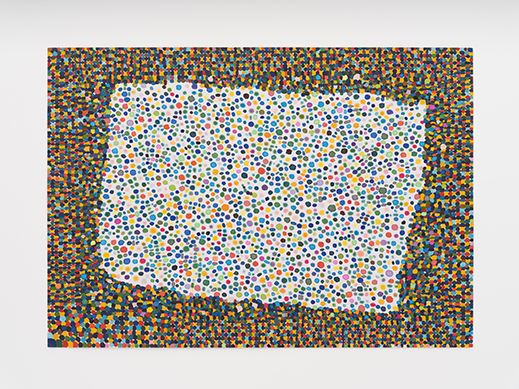

Moriya Kishaba, Untitled (Dot) (2014), artist's collection |

The written word is also a key element in Moriya Kishaba's works. Since childhood, the Okinawa native, born in 1979, has enjoyed partially or completely filling sheets of paper with writing. Initially, Kishaba preferred the alphabet, but after entering high school he switched to kanji. He tends to start a work in the lower left-hand corner with the character for "stone" -- probably because it is part of his street address. Some of Kishaba's pictures contain a slightly curved column of tiny kanji on one side of the paper or a tiered rock formation of characters at the bottom. Most of the paper is completely blank, creating a stunning contrast between the black ink and white space. Kishaba's other passion is dots. He draws jagged borders of small brilliantly colored circles around the edge of the paper, and fills in the center with a less densely populated collection of dots, recalling the patterns in a color perception test.

Momaka Imura, Button Ball (2013), Atelier Yamanami |

Shiga-born Momoka Imura's Button Balls are small fabric balls covered with buttons and clumps of thread. Imura (b. 1995) begins by choosing a piece of cloth, sews buttons of various colors and sizes on it, and then rolls the fabric into a ball. She repeats this process several times, covering the ball with each new cloth and changing its color until she is satisfied with the results. Imura is fond of stroking her creations, and has also been known to adopt the persona of a children's TV host, complete with pink wig, and sing and dance while she works.

Yuki Fujioka, born in Kumamoto in 1993, makes delicate paper works that look like a cross between a comb and a feather. Since discovering scissors as a child, Fujioka has used them to rhythmically cut all kinds of paper that he finds around the house. In some cases, he adds color to the back of the paper with crayons, and the front bears traces of what may have been a handbill or a page from a magazine. Over the years, Fujioka has taken to cutting the paper into thinner and thinner, almost thread-like pieces. Every work is fashioned out of a single sheet of paper, and some have a border running across the top or a U-shaped enclosure with a knob on one side, framing the beautifully curled paper strands. Color combinations like pink and black give the works a charming appearance, and to top each one off, Fujioka adds a diagonal cut as a kind of signature.

|

|

Yuichiro Ukai, Monsters (2021), Atelier Yamanami (© Yuichiro Ukai / Atelier Yamanami, courtesy of Yukiko Koide Presents) |

The paintings of Shiga native Yuichiro Ukai (b. 1995) are filled with creatures such as dinosaurs, skeletons, and monsters. They are often reminiscent of Japanese scroll paintings from the 16th century in their depiction of parades of dozens, if not hundreds, of highly detailed yokai or animals. Ukai's Monsters (2021), a 14-meter scroll assembled from 82.5-centimeter-wide panels of cardboard, is a riot of activity with quotations from every conceivable source. Sun Wukong, the Monkey King from the Chinese epic Journey to the West, stands side by side with triceratops skeletons, giant banjos and basses, Japanese military commanders with prominent mustaches, the cartoon superhero Anpanman, and every so often a sign or banner reading "Safety Matches" or "Best Matches." Ukai gained international attention when a similar work of his, Yokai (2019), was acquired by the American Folk Art Museum in New York in 2020.

The very sizable final room in the exhibition is taken up with a display of pictures tracing the artistic development of Kodai Nakahara (b. 1961) since childhood. Interspersed with learning materials, his drawings and paintings are arranged chronologically across several long tables, followed by some wall charts Nakahara made surveying shells and other natural phenomena as well as oil paintings dating from his high school years. The artist has presented the piece, titled Educational, on a number of occasions since 2017 with slightly different content. Its inclusion here prompts us to consider the pros and cons of artistic training, and how Nakahara's early creative spontaneity compares to his later technical prowess.

The exhibition ends with a paper-covered table and a few colored pens just outside the exit. Here's your chance to do what comes naturally: create. That should be a cinch after this special opportunity to see so many innovative works by visionary artists.

|

|

Exhibition view of Kodai Nakahara's Educational (photo by Shunsuke Kato, NOTA & design, courtesy of the Shiga Museum of Art) |

All images provided by the Shiga Museum of Art.

|

|

|

Christopher Stephens

Christopher Stephens has lived in the Kansai region for over 25 years. In addition to appearing in numerous catalogues for museums and art events throughout Japan, his translations on art and architecture have accompanied exhibitions in Spain, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, South Korea, and the U.S. His recent published work includes From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and Gutai: Splendid Playground (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2013). |

|

|

|