|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Takamasa Yosizaka: Redefining Architecture at All Scales

James Lambiasi |

|

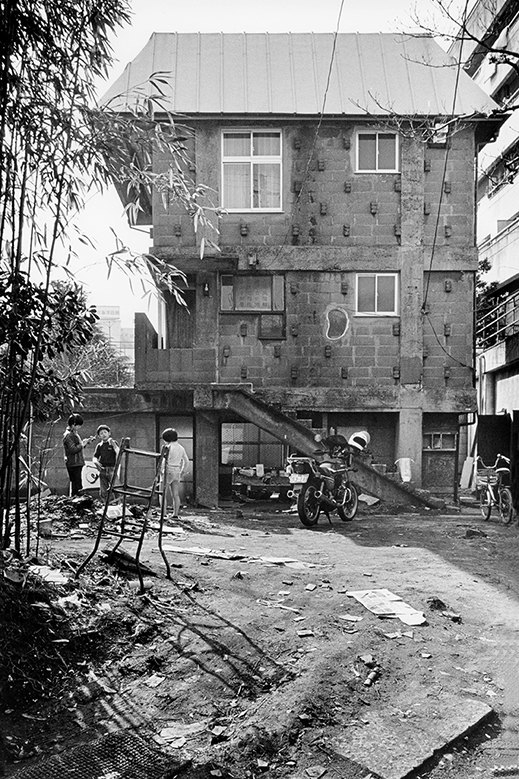

Inter-University Seminar House (1965). Photograph by Eiji Kitada, 1997 |

Takamasa Yosizaka (1917-1980) is well known as one of the three Japanese architects who worked under the great modern master Le Corbusier, an experience that subsequently positioned him at the forefront of modern architecture as it developed in Japan. While one could say his counterparts Kunio Maekawa and Junzo Sakakura enjoyed more architectural acclaim globally, this should not diminish the profound influence that Yosizaka has had on Japanese modern architecture. The exhibition Yosizaka Takamasa Panorama World: from life-size to the earth at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo highlights the importance of Yosizaka's life and architectural achievements in the most comprehensive retrospective of his work in a public art museum to date.

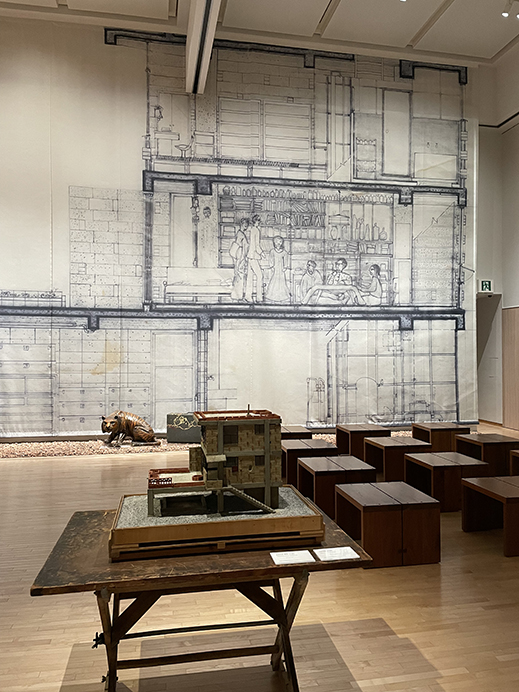

Through seven different sections or "chapters," the exhibition pieces together the activities of Yosizaka's life as a person, architect, world traveler, and social critic. "Chapter 2: Yosizaka House," for example, helps us understand his personal life as an architect by focusing on his own home. Scale was a fluid concept to Yosizaka, who saw the house and family as the base of community in society. The modest concrete deck of the house captures the essence of his emerging philosophy of "artificial ground," which saw the construction of architectural planes as a solution for creating new urban space out of the ashes of World War II. Dramatically enlarged to life size, a section sketch of Yosizaka House including his family is featured prominently on the wall, with a model of the house occupying the space in front. It is interesting to note that the size of the area in front of the life-size section is roughly equivalent to the house's garden, giving us a feel for the scale of the space.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yosizaka House (1955). Photograph by Eiji Kitada, 1982

|

|

In the foreground, a model of Yosizaka House (scale 1:30), collection of Waseda University Architecture Department Honjo Archives. In the background, a measured section drawing (scale 1:1), property of the National Archives of Modern Architecture, Agency for Cultural Affairs. Photo by James Lambiasi |

In "Chapter 3: The Idea of Architecture," we discover Yosizaka's methodology in working with concrete form. While other architects during the postwar reconstruction boom focused on pristinely refined forms, Yosizaka resisted this tendency and chose to concentrate on inspiration from human activity. We can see this in the models he would sculpt by hand in clay, which illustrate his fascination with form following function in a fluid and organic way to connect people with place. The concrete structures of Yosizaka's Inter-University Seminar House complex, for example, demonstrate his deep interest in human-based design, in which architecture is not an end in itself, but a tool to help guide and nurture social interaction. I can speak first-hand regarding this, as in the late 1990s I enjoyed staying at the Inter-University Seminar House as a workshop instructor. The village-like complex knits in seamlessly with the landscape, as if he had used the clay models to extract the structures from the ground itself.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

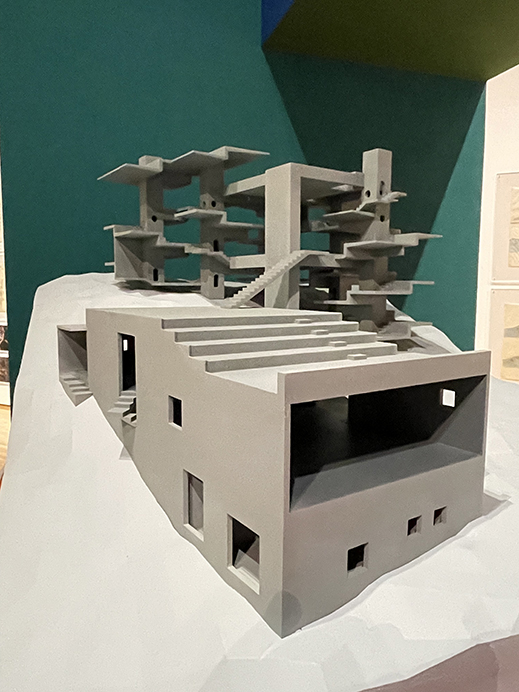

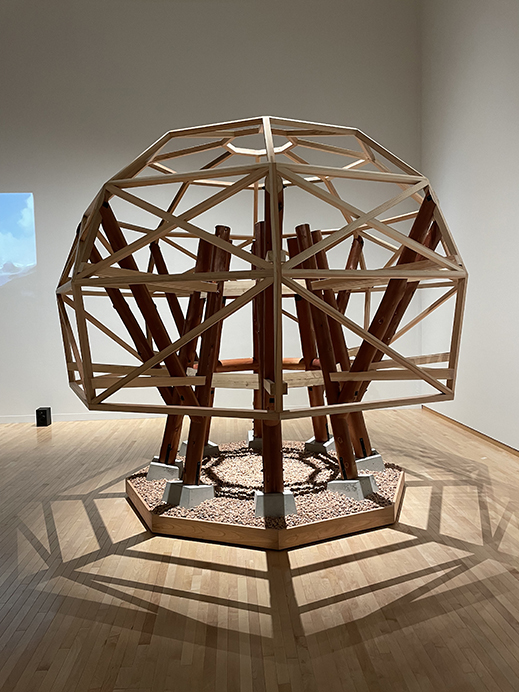

Extended-stay House in the Inter-University Seminar House complex, structure model (scale 1:50). Photo by James Lambiasi

|

|

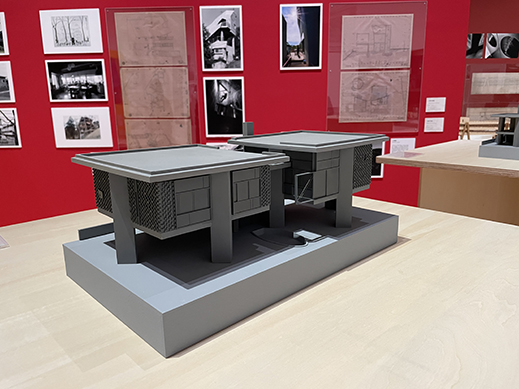

Ura House, model (scale 1:50). Photo by James Lambiasi |

The structure model of the Extended-stay House (part of the Inter-University Seminar House complex) is enlightening; although the building itself has rather nondescript red wood siding, the absence of walls in the model reveals floors that are actually a spiraling series of oversized steps. This unorthodox arrangement of sleeping spaces creates separate zones while simultaneously connecting the living spaces among residents, illustrating Yosizaka's passion for experimentation with space and human interaction.

Ura House, built for mathematician Taro Ura, also shows the depth of Yosizaka's design intentions, which can recognize human connections at various scales. While built as a single-family house, the two square living units raised off the ground by pilotis to shelter an exterior living zone below actually originate from a larger town planning concept to create and nurture communities.

|

|

|

|

|

Kurosawaike Hütte, structure model (scale 1:3). Photo by James Lambiasi

|

Yosizaka saw form as an extension of the collaborative process, and consequently believed it is imbued with life. Rather than trying to develop a particular stylistic design as an architect, he eschewed that approach in favor of starting from scratch with each design problem. For example, "Chapter 4: Mountains, Snow and Ice, Architecture" presents Yosizaka connecting his passion for mountaineering with architecture by designing several mountain lodges. A 1:3 scale structure model illustrates the circular form he devised to shed snow -- the result of a collaborative process to find a solution, as opposed to inventing for the sake of form.

The last section of the exhibition, "Chapter 7: To Iukeilogy," displays Yosizaka's humanistic approach to architecture through a prolific number of illustrations, publications, and urban design proposals. For Yosizaka, architecture was inseparable from the values of community and human equality, and he passionately tried to illustrate these concepts through his visual depictions. He famously redrew maps with shifted orientations, pointing out that even the standardization of maps and political boundaries is fraught with injustices of the past. Flipped Map resets our orientation by positioning the Japanese archipelago horizontally; by viewing the Pacific Ocean hovering over Japan, Yosizaka opens our eyes to the powerful connection between societal hierarchy and the visualization of our built environment.

|

|

View of Flipped Map from The Japanese Archipelago in the 21st Century: From a Pyramid to a Mesh (1970), with a hanging model of Dice World Map (1942), ©Yosizaka Takamasa. Photo by James Lambiasi |

Evaluating the architectural achievements of Yosizaka has been an elusive endeavor when placed in the context of other modern Japanese architects of his era. Fortunately, the seven chapters of this exhibition piece together all facets of his life, both personal and philosophical, clarifying his importance as an architect. Exemplifying Yosizaka's philosophy of "discontinuous unity," according to which design based on collaboration is able to create unity while not sacrificing the individual identity of each part, the exhibition knits together a comprehensive view of his achievements while celebrating the individuality and depth of each separate facet of his life.

All photos published by permission of the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo. |

|

|

James Lambiasi

Following completion of his Master's Degree in Architecture from Harvard University Graduate School of Design in 1995, James Lambiasi has been a practicing architect and educator in Tokyo for over 26 years. He is the principal of his own firm James Lambiasi Architect, has taught as a visiting lecturer at several Tokyo universities, and has lectured extensively on his work. James has served as president of the AIA Japan Chapter in 2008, and frequently appears on the NHK series "Journeys in Japan" as an architectural critic. |

|

|

|