|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Northern Exposure: Tohoku Art and Crafts from 1930 to 1945

Jennifer Pastore |

|

Taut: An Akita Journey chronology display (installation view) |

Tohoku and Japanese Culture

Tokyo Station Gallery is showing Eyes on Tohoku 1930-1945, an exhibition of folk crafts and art affiliated with northeastern Japan during the prewar and World War II years. This was a period when, as the curators note, the country was at a crossroads, straddling divides of tradition and modernity and rural and urban life. Tohoku (Aomori, Akita, Iwate, Miyagi, Yamagata, and Fukushima Prefectures) accounts for 30 percent of the land on Japan's largest island. For millennia it has sustained the rest of the nation as a vital source of food, transportation, military power, and energy.

In the early 20th century (and still somewhat today), Tohoku was often viewed as an impoverished hinterland, snowbound and backwards. In many ways it did lag the rest of the country, its inhabitants stuck tilling the land while people further down the archipelago reveled in Taisho freedoms and Showa modernism. But this is a view that ignores the history and reality of Tohoku, a vast and diverse area that for more than 150 years has seen its population killed or displaced and its resources exploited in the name of building the modern Japanese nation state.

For its part, Tohoku has never seemed particularly concerned with Japan's frenzied modernization. It was dragged kicking and screaming into the Meiji era (1868-1912) and could theoretically still be a feudalist society today if a few end-of-shogunate battles had gone differently. Fukushima's Aizu domain put up especially fierce resistance to Meiji rule, holding out in its medieval castle for an entire month in 1868. (This conflict, part of the Boshin Civil War, would have been within living memory in 1930.) Such tensions are worth recalling when faced with the narrative of a "bloodless" Meiji Restoration said to have smoothed Japan's way to the modern age; they should also be remembered while admiring Tohoku artifacts touted as quintessential specimens of "Japanese" culture. What really is Japanese culture, and who gets to define it?

|

|

Designs by Bruno Taut. Right: Magazine Rack (1935), Yamagata Prefectural Museum; left: Small Wooden Chest (1937), Gunma Prefectural Museum of History |

Bruno Taut

Tohoku welcomed the renowned German Expressionist architect Bruno Taut in 1933. He was invited by the International Architecture Association of Japan to lecture on international design at Sendai's Kogeishido (Industrial Art Institute), where he came to influence important Japanese designers like Isamu Kenmochi. Taut found much to admire in the aesthetic economy of certain kinds of Japanese art, but -- always the advocate of clean Modernist lines -- he grew frustrated with other designers' inability to purge their work of what he called "kitsch." Famously, he praised Kyoto's austere Katsura Imperial Villa as the finest example of Japanese architecture and denounced Nikko's ornate Toshogu Shrine as the worst. (Perhaps, instead of placing both under a broad umbrella of "Japanese design" and judging one as superior, he could have simply noted the diversity of architectural styles in Japan.)

|

|

|

|

|

Right: Mino (Date gera) Straw Raincoat (1934) from Miyagi Prefecture, The Japan Folk Crafts Museum; left: Bandori Back Rest (1939) from Yamagata Prefecture, The Japan Folk Crafts Museum

|

A fed-up Taut left Miyagi for Gunma Prefecture in 1934 but made repeated trips to Tohoku during his remaining two years in Japan, documenting his experiences in photographs, drawings, and publications exhibited here. A chronological presentation of his time in Akita in 1935 and 1936 features charming illustrations by the Akita-born printmaker Tokushi Katsuhira. The display details Taut's "expeditions" north, showcasing the clothing, tools, and other objects he collected there. His exposure to Tohoku culture naturally influenced his work, and the exhibit offers examples of his designs crafted with the natural materials he encountered there. (A bamboo magazine rack and a straw clutch particularly demonstrate a sort of rustic chic.) As the exhibition text notes, "Taut's crafts are imbued with the beauty, skill and attention to materials that he found in Japan. This should be recognised as part of Taut's design legacy."

|

|

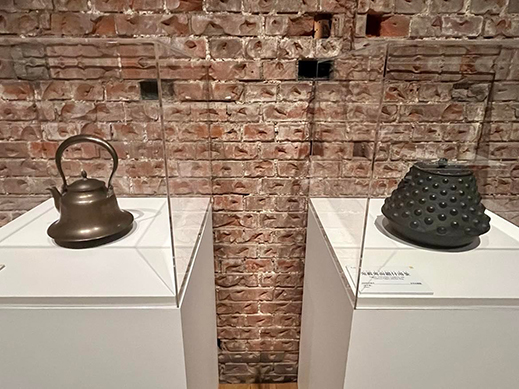

Right: Yugama Hot Water Cauldron with Hailstone Pattern (late 1930s) from Iwate Prefecture, The Japan Folk Crafts Museum; left: Habiro tetsubin Iron Kettle from Yamagata Prefecture, The Japan Folk Crafts Museum |

Keisuke Serizawa's illustrations for Teshigoto no Nihon (Handicrafts of Japan) (1945), The Japan Folk Crafts Museum |

Tohoku and Mingei

Tohoku played an indispensable role in the 20th-century Mingei folk craft movement, which found beauty in handcrafted utilitarian objects and sought to preserve and promote them. Soetsu Yanagi, the movement's founder, may have been among the first cultural authorities to acknowledge Tohoku's artistic merit, calling it "a cradle of rich culture" and visiting more than 20 times between 1927 and 1944. The exhibition spotlights an array of Tohoku crafts, from glazed pottery and ironware to mino straw coats (called kera or gera in the region), traditionally made by Tohoku grooms for their brides. Echoes of the sleek and sturdy elegance of the region's metalcraft can also be found in the work of Yanagi's son, the prominent industrial designer Sori Yanagi.

The textile artist Keisuke Serizawa was another Mingei protagonist who took an active interest in Tohoku. His works here include a colorful map of crafts across Japan and iconographic illustrations of Tohoku treasures published in Teshigoto no Nihon (Handicrafts of Japan).

|

|

Kokeshi Dolls from Akita (upper left), Miyagi (upper right), and Iwate (lower center) Prefectures |

Kokeshi

Toys are included in the canon of folk art. Tohoku produces a wealth of them, perhaps most famously the armless and legless kokeshi dolls found across the region with local variations in shape and decoration. Tokyo Station Gallery presents an impressive cohort of kokeshi, numbering in the dozens with representatives from all six prefectures. While generally characterized by red and black coloring and smooth, round heads on narrow necks, kokeshi facial expressions are often unique to each doll. They are said to have originated in Tohoku hot spring towns around the end of the Edo period. By the 1940s, kokeshi would become a tourism magnet and ultimately, a symbol of Japan.

Installation view with Tohoku folk toys and (in background) hanging scrolls from Shiko Munakata's In Praise of the Tohoku District (1937), The Japan Folk Crafts Museum |

Snow and Its Discontents

In the 1930s, on top of the global economic depression, Tohoku was facing poor harvests caused by record-breaking cold and other environmental disasters. It also bore the onus of feeding a growing Japanese population intent on expanding its empire. At the insistence of a Diet member from Yamagata, the federal government finally decided to attempt to conquer one of Tohoku's greatest adversaries, a formidable and defining one it had grappled with for eons: snow. In 1933, Japan's Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry established the Research Institute of Agrarian Economy in Snowbound Districts (a.k.a. "Setcho") in Shinjo, Yamagata. Setcho's mission was to study and address snow damage, diversify the economy of farming villages, and provide training to farming community leaders. A highlight of the exhibition's "Setcho" segment is an excerpt from Tokichi Ishimoto's 1938 documentary Snow Country. Filmed in Shinjo, it captures the burden and beauty of life in a remote place ruled by nature.

Setcho also brought the Mingei movement on board, tasking it with promoting and developing folk craft products to broaden the Tohoku economy beyond agriculture. Soetsu Yanagi, Keisuke Serizawa, and others organized workshops, drafted designs, and established sales channels with exhibitions at Tokyo department stores. In 1940, the French architect Charlotte Perriand became involved as a design advisor at the invitation of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry. Asked to create prototypes for products using Yamagata folk tools and materials, she came up with items such as the covetable chaise lounge on exhibition. This creative fusion of traditional and Modernist design was outfitted with a folding cushion woven of straw and birch bark in a way similar to a mino coat. It proved popular at Takashimaya stores in Tokyo and Osaka.

|

|

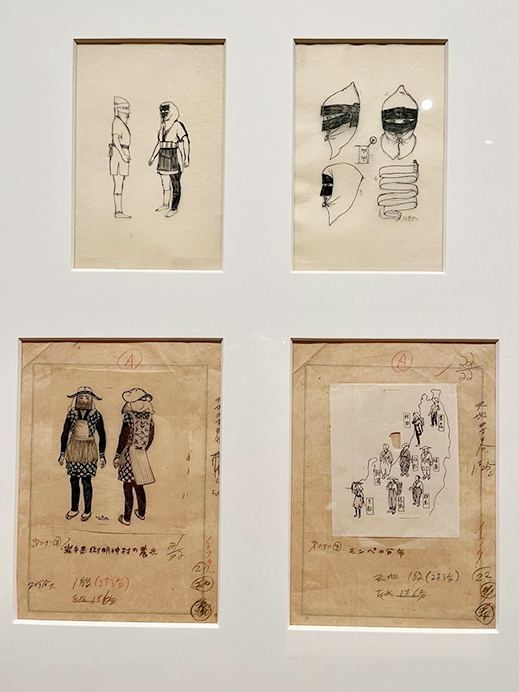

Wajiro Kon's illustrations of Tohoku farming clothes (c. 1938-1939), Kogakuin University Library |

Junzo Kon's lithographs from Aomoriken gafu (Picture Book of Aomori Prefecture) (1933-1934), private collection |

Wajiro and Junzo Kon

The Aomori-born architect and ethnologist Wajiro Kon lent his talents to the Setcho cause as well. An expert on minka farmhouses, he reimagined them specifically for snow country with slanted roofs and upper-level entrances. Furthermore, he applied his "Modernology" approach of inspecting and recording the details of a place -- famously deployed on the Taisho-era fashions of Ginza -- to the lifestyles of Tohoku. Many of his illustrations depicting regional clothing, buildings, and customs are exhibited here. His lesser-known brother Junzo, also a designer, began his own Modernology surveys after returning to Aomori in the wake of the 1923 Kanto Earthquake. Junzo's research culminated in the print collection Aomoriken gafu (Picture Book of Aomori Prefecture). Compared to his brother's matter-of-fact depictions, Junzo's works display more artistic interpretations of his subjects, which he rendered with a poetic, sometimes slightly surreal touch.

|

|

Installation view of works by Tadashi Yoshii with Tohoku-ki (A Report of Tohoku) (1941-1944) in center case, Showa no Kurashi Museum |

Tadashi Yoshii

Conditions in Tohoku only grew more difficult during World War II. Setcho fell by the wayside, and the government demanded higher productivity from the region even as supplies became increasingly scarce. Artists nationwide found themselves under heightened scrutiny by the police. Among them was the Fukushima-born painter Tadashi Yoshii, who had studied Surrealism abroad and witnessed the debut of Picasso's Guernica in Paris. Back in wartime Tohoku, Yoshii -- much like the Kon brothers -- set out on research trips and immersed himself in the life of farming and fishing villages in Aomori and Fukushima. His copious sketches and notes were compiled in Tohoku-ki (A Report of Tohoku) (1941-1944). Yoshii was also instrumental in establishing the Tohoku Lifestyle and Art Study Group, a collective of Tohoku artists dedicated to representing the region. They held their first exhibition at Tokyo's Shiseido Gallery in 1943, choosing two oil paintings by Yoshii for display. In the Social Realist style required by the times, Yoshii had painted a woman with a foot plow and a slice-of-life tableau from the Akita village of Kemanai. These works -- much like the Eyes on Tohoku exhibition itself -- convey the vigorous determination of a place that above all knows how to survive, with or without the recognition of the outside world.

The Showa no Kurashi Museum in Tokyo's Ota Ward includes a room dedicated to the work of Tadashi Yoshii.

All photos by Jennifer Pastore, courtesy of Tokyo Station Gallery. |

|

|

Jennifer Pastore

Jennifer Pastore is a Tokyo-based art fan and translator. In addition to Artscape Japan, her words have appeared in ArtAsia Pacific, Sotheby's, and other publications. She served as editor at Tokyo Art Beat for seven years. |

|

|

|