|

|

|

Nameless Genius, Unconscious Beauty: The Nihon Mingeikan

Alan Gleason |

|

|

|

|

The special exhibit room of the Mingeikan. |

Better known by its Japanese name, Nihon Mingeikan, the Japan Folk Crafts Museum has been a deservedly popular stop on Tokyo's foreign tourist circuit for many decades. What makes the Mingeikan uniquely appealing among Tokyo museums is its dedication to utilitarian works created by anonymous craftspeople. If there is a prevailing aesthetic, it is shibui -- subdued, unpretentious, exquisitely tasteful. The natural browns of unpainted wood and dark blues of indigo-dyed cloth are the dominant hues throughout the building.

The Mingeikan's founder, aesthetic philosopher Soetsu Yanagi, coined the term mingei (literally, "crafts by and for the people") and launched the folk art movement by that name in the 1920s. Designed by Yanagi and built across the street from his home in Komaba, which still stands, the Mingeikan opened its doors in 1936. Resembling a huge kura -- a traditional Japanese storehouse -- in appearance, it holds some 17,000 items, most of them collected by Yanagi himself in the course of his ceaseless travels into the hinterlands of Japan and elsewhere in East Asia. Since there is room to display only about 500 items at one time, the displays rotate once every three months or so. Pottery, lacquerware, handwoven textiles, Buddhist carvings, rubbings and woodblock prints predominate, nearly all created by anonymous Japanese artisans between the 16th and 19th centuries, with a few works from Korea and China.

Perhaps in keeping with the museum's overall aesthetic, the labeling is steadfastly minimalist -- "Lacquer bowl, Edo period, Shinshu province" is about the most you can hope for. It is also entirely in Japanese, which is a bit surprising given the popularity of the place with foreigners. (On the Sunday afternoon I visited, over half the visitors were fellow gaijin.) Still, the lack of detailed data may be a blessing in disguise; it is nice, for a change, not to have your attention diverted from the work itself to an exhaustive description of it, as tends to happen to me at other museums.

Besides its rotating collection, the museum devotes a couple of rooms to ongoing exhibits. One is of traditional Korean pottery, Yanagi's first and possibly greatest passion. Another features works by the only "named" artists on display, fellow Mingei activists and close friends of Yanagi like the potter Shoji Hamada, the woodblock artist Shiko Munakata, and the stencil dyer Keisuke Serizawa (whose bright bingata-inspired calendar designs are beloved by many Japanophiles).

One can't help wondering if the Mingeikan's cachet with tourists from abroad has much to do with the way the rustic, quiet, "unconscious" (to use Yanagi's word) beauty of its collection coincides with Western expectations of what Zen and nature-inspired Japanese art should look like. Then again, Yanagi was truly fond of Buddhist folk art, and it so happens that Buddhist images make up the greater part of the current (until March 23) special exhibit, "Beauty of Woodblock Prints and Stone Rubbings." Indeed, one of the points of this show is to highlight a significant genre of Japanese woodblock art that often gets lost in the shadow of the gaudier and bawdier ukiyo-e.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The main stairway inside the Nihon Mingeikan. |

|

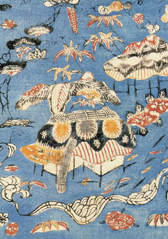

Design of Scene in Naeshirogawa (detail), stencil dyed on cotton, by Keisuke Serizawa (1955) |

|

|

|

| Images courtesy of Nihon Mingeikan. Reproduction without permission is expressly prohibited. |

|

|

|

|

|

Japan Folk Crafts Museum (Nihon Mingeikan) |

|

|

|

4-3-33 Komaba, Meguro-ku, Tokyo / Phone: 03-3467-4527 |

|

Open 10-5 (Closed Monday and the year-end and new year holidays)

Transportation: 5 minutes walk from Komaba-Todaimae station on the Keio Inokashira Line (two stops west of Shibuya station) |

|

|

|

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 24 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 | 2 | |

|

|

|

|

|