|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mugonkan: Pictures Worth Ten Thousand Words

Alan Gleason |

|

|

|

|

The main hall of the Mugonkan on Mt. Sanno in the Chikuma valley, Nagano Prefecture

|

|

The chapel-like interior of the Mugonkan

|

The Mugonkan sits atop a hill overlooking the verdant Chikuma River valley outside of Ueda city, an hour and a half northwest of Tokyo by Shinkansen. Though the name can be loosely translated "Museum of Silence," this unique institution is hardly mute in its testimony to the destructiveness of war on a personal level. The purpose of the museum is to exhibit works by young Japanese artists who died in their prime -- or before it -- on the battlefields of World War II.

I found myself emotionally incapable of judging the art on the Mugonkan's walls by strictly aesthetic standards. One cannot help but view every work through the prism of its creator's death. Each painting (most of the works are oils) is accompanied by a brief biography of the artist: when and where he was born, what schools he attended, and when and where he died. (All the artists are male, for the obvious reason that all were conscripts.) Most died in their early twenties.

The paintings themselves rarely depict scenes from the front. Although there are display cases housing letters and postcards with innocuous sketches of camp life (only subject matter acceptable to the censors made it back to Japan), most of the works were painted before the artists were sent off to war. Portraits and landscapes predominate, not surprisingly given the conservative bent of Japan's art schools, particularly in the political climate of the thirties and forties. All are well executed, as befits graduates of Japan's top art schools, which most of these artists were. In a few cases one sees glimpses of talent and promise that make the knowledge of their premature deaths all the more heart-rending.

|

|

|

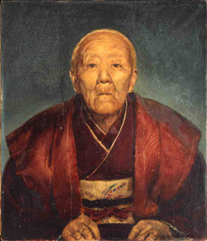

Kiyoshi Hachiya, "Portrait of Grandmother,"

oil on canvas, 53.0 x 45.7 cm |

|

|

Adding to the poignance of their stories is the fact that the majority seem to have died in the jungles of Asia in the very last months -- or weeks -- of the war. Typical are Michio Maeda, who died in the Philippines in early 1945 after sending 400 postcards to his wife. Or Manpei Nakamura, killed in China at age 26, having already survived his young bride, who had died after childbirth back in Japan. Or Kiyoshi Hachiya (whose portrait of his grandmother appears here), dead in Leyte at age 22, six weeks before Japan surrendered.

The museum is the brainchild of one man, Seiichiro Kuboshima, a successful Tokyo businessman who became interested in the life and work of artists who died young, whatever the cause. An encounter with an artist who had survived the war, but told of his many comrades who had not, launched Kuboshima on a trek across Japan in search of the works of those artists. With the aid of the wartime graduation rosters of such institutions as the Tokyo Fine Arts School and the Imperial Art School (forerunner of today's Tama and Musashino Art Universities), he tracked down the surviving families of the war dead and cajoled them into granting permission to display their sons' or husbands' paintings.

With the help of thousands of donors and the city of Ueda, Kuboshima honored the commitment he made to those families, completing the Mugonkan in 1997. He wanted to build it in Ueda, he says, because it was the hometown of one of the first young artists whose works he collected. Today the collection occupies two attractive concrete buildings somewhat reminiscent of medieval European cloisters. It currently consists of some 600 works by 108 artists, which are displayed in rotation.

Though there is nothing in the Mugonkan's literature that betrays a political motive (and Kuboshima denies he built it with any), the antiwar message it conveys is impossible to ignore. Nor has the museum escaped the attention of Japan's right wing, which apparently views it with a disdain that has prompted occasional acts of vandalism.

So one does not go to the Mugonkan as an exercise in art appreciation. It is, inevitably, a statement, a nearly overwhelming one, about young lives wasted in war. That the lives in this instance were those of budding artists merely bludgeons the point home. The impulses that give birth to art and artists are, after all, the antithesis of the impulse to war. Even in their censor-approved letters, few of these young men voice the rote oaths of allegiance to country and Emperor that were the standard litany of the day. It is obvious that they wanted more than anything to return home alive and get on with their first love, painting.

|

|

|

| Hiroshi Izawa, "Family," oil on canvas, 73.0 x 90.8 cm |

|

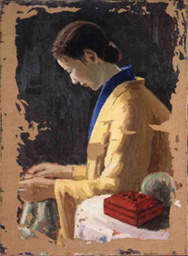

Takeshi Korogi, "Woman Weaving," oil on canvas, 72.0 x 53.0 cm

All photos courtesy of Mugonkan

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mugonkan |

|

|

|

3462 Koaso Sannoyama, Ueda City, Nagano Prefecture

Phone: 0268-37-1650

Open 9:00-5:00 daily, July-November (to 6:00 in July and August); closed Tuesdays, December-June

Transportation: 30 minutes walk or 10 minutes by shuttle bus from Shiodamachi station on the Ueda Dentetsu Bessho Line, or 20 minutes by taxi from JR Ueda station |

|

|

|

|

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 24 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|

|